Karina Longworth’s long-running podcast about classic movies, You Must Remember This, sets out to tell the “secret, and/or forgotten history” of Hollywood in its much-mythologized golden age. Her new book, Seduction, offers an insistent, clear-eyed reminder of the fact that history does not get buried or forgotten by accident, but by design, in order to burnish and elevate the reputations of powerful men, and to cut women down to size.

It may seem surprising, at first, that Longworth’s central subject in this book is a powerful man: Howard Hughes, who dominated American culture in the middle of the 20th century, defining and embodying what it meant to be a millionaire, a mogul, and a madman. Born in Houston in 1905, Hughes lost both of his parents in his late teens and inherited the family business, which manufactured the drill bits needed to cut through the earth to get to oil. Before he was 20 he had strong-armed his grandfather and other relatives out of the company, gotten himself declared a legal adult, married a Houston heiress, and decamped for Hollywood, where he set himself up as a producer-director.

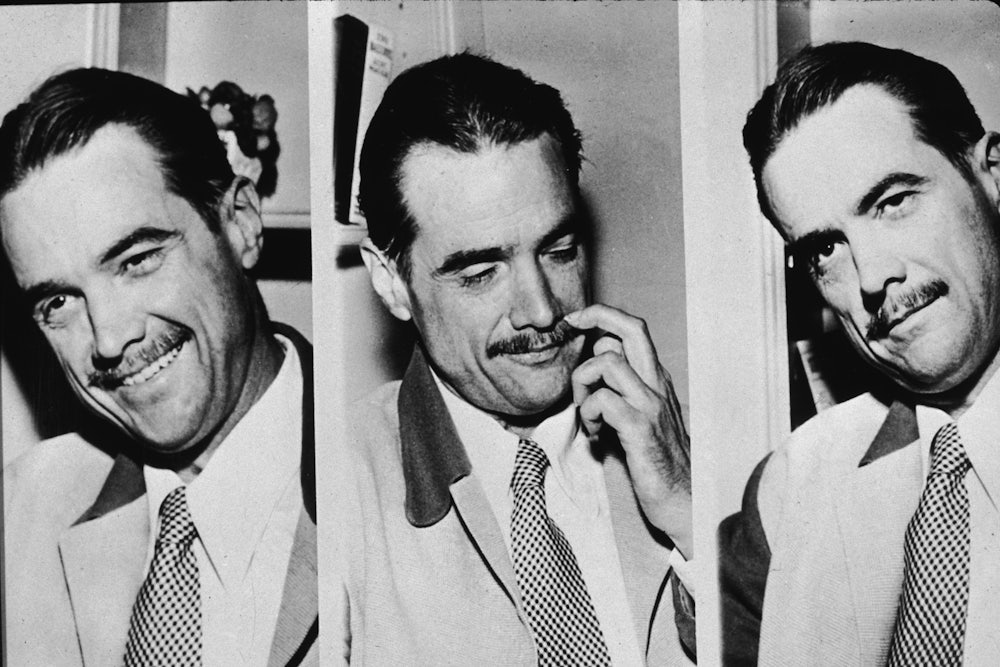

His obsessions at the time were golf, aviation, movies, and money—eventually, women would replace the golf. For the next 30 years he occupied a unique position in American culture. He was a perennial outsider in the movie business, who undertook wildly ambitious feats of engineering, filmmaking, and flying, and was paired with all the most beautiful women in Hollywood. Cushioned by his wealth, he was eventually brought down not by his enemies but by his own inner demons.

If modern readers know much of Hughes’s story, it is likely through Martin Scorsese’s visually inventive and emotionally shallow 2004 biopic The Aviator. Leonardo DiCaprio plays Hughes as a nervy milquetoast whose problems stem from the erotically-charged dominance of his mother. The film minimizes Hughes’s aggressive, transactional, and compulsive womanizing, and instead implies that he was at heart a one-woman man—that woman being Cate Blanchett’s cartoonishly swaggering Katharine Hepburn. Hughes’s interactions with women are supposed to demonstrate the hypnotic power of the man and his money—as when he propositions a cigarette girl in a nightclub. We’re given to understand that this is just how Hollywood works.

Longworth’s story of Hughes and the world he built and controlled is a lot more complex. It illustrates the many ways in which the Texan outsider did not conform to Hollywood’s values. It has the pace and intensity of a true crime story, which in a way it is. Longworth downplays the legendary weirdness of her subject and emphasizes the ways he gamed a system set up to work for him. Instead of focusing on Hughes as the hero (or anti-hero), as most Hollywood histories have tended to, she instead seeks out the stories of the women who lived and worked in the riptide of his influence. By unearthing unpublished material from the archives of Hughes and his contemporaries, and, more often, by astutely reading between the lines of official histories, Longworth shows how valuable and revealing it is to tell the story of a playboy from the perspective of his toys.

The book opens with an account of a party one night in 1925 at the Cocoanut Grove, the lavish nightclub inside Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. Frederica Sagor, a screenwriter in her mid-twenties, witnessed the events and described them in a candid memoir of her early career, published in 1999 shortly before she turned 100. Sagor recalled watching as her “drunk, drunk, drunk,” half-undressed middle-aged bosses pawed at young women hired or lured for the evening, yet she showed little sympathy for the women who allowed themselves to be traded hand to hand like poker chips. The men were acting as men would always act. But if a woman wanted to be anything more than “a call girl—half naked, lying across a chair, her hand stretched out to receive a hundred-dollar bill,” then it was up to her to resist, Sagor thought.

Longworth uses Sagor’s story to kick off a much larger investigation into the colossal power imbalance between men and women in Hollywood—which persists to this day—and to show how hard it was for any woman, within that system, “to sell something other than her body to Hollywood’s men.” This was marginally easier in the early days, before the Hollywood star-making system was established, run and regulated by men. In the early silent era, women like Lois Weber could write and direct their own stories about the state of the world and the place of women within it. But by 1933, when fifteen-year-old British actress Ida Lupino arrived in Hollywood, there was already an established version of every kind of on-screen woman one could be. Lupino began as a new Jean Harlow, the bleach-blonde star of Howard Hughes’s World War I melodrama Hell’s Angels. She soon tired of that game and tried actually acting, becoming, for Warner Bros., a cheaper version of their biggest star, the “notoriously choosey” Bette Davis.

Then she decided to try something that fit no pattern that anyone, in the late 1940s, could recall—becoming a director herself. Lupino used marriage and what she called her “maternal wiles” to carve out a publicly acceptable image, so that she could make the subversive movies she wanted, inspired by the Italian neorealists—like the phenomenally successful low-budget drama Not Wanted, which told the stories of unmarried mothers. Longworth is astute on the pressure Lupino was under, in one of the most flagrantly misogynistic eras in modern American history, to establish herself as a professional without appearing to be so: She became known on her sets as “Mother” and portrayed herself in the press as a nurturing figure, whose primary commitment was still to her husband and family, rather than her creative work. “No director of the era,” Longworth writes, “worked as hard to diminish the public perception of their own power.”

Lupino was responding to a changed postwar Hollywood, which reflected a distaste for proudly independent women in the wider culture. Katharine Hepburn was one of the few women at that time who was able to, as Longworth puts it, “carve out spaces for her own freedom thanks to her alliances with powerful men.” Hepburn met Hughes in 1935 when he landed his airplane in the middle of the set of the movie she was filming. She thought the move was a cheap stunt, and was furious with her costar, Cary Grant, for inviting his buddy to show up unannounced.

It would be two years and two more serious romances on her part before Hepburn publicly partnered with Hughes, shortly before she was infamously blasted as “box office poison.” The gossip columns latched onto the story of “the damsel in distress rescued by a dashing aviator,” but they were more alike, and more equal, than that. Hepburn was, like Hughes, something of a daredevil and a germophobe; she was also wealthy in her own right, and carefully guarded her privacy. The romance worked for them both: It suggested that Hughes could be attracted to a sharp and smart woman, and it helped affirm Hepburn’s heterosexuality, which was frequently called into question, mostly due to her outspokenness, love of pants, and living with a female roommate.

In 1938, Hughes completed a record-breaking round-the-world flight, becoming “the most famous man in the world”—and newspapers everywhere speculated on whether he would propose. In fact, he had, more than once, but Hepburn turned him down. Shortly afterwards, she met Spencer Tracy, the love of the rest of her life. After his death, Hepburn burnished her relationship with Tracy as the ultimate Hollywood romance—but during his lifetime, and the nine films they made together, the relationship stayed secret, as Tracy was married. That meant that for a long time Hughes was Hepburn’s highest-profile romance. Again and again, Longworth’s book shows that power in Hollywood depends on who’s in charge of the story.

The roster of famous names with whom Hughes was paired throughout the 1930s and 1940s is seemingly endless, but it represents only a fraction of Hughes’s voracious appetite for women. Those high-profile actresses—silent star Billie Dove, Jean Harlow, Ava Gardner, Ginger Rogers, Ingrid Bergman, Jane Russell, and many others—managed to carve out a modicum of power for themselves in a ruthless business largely through their romantic relationships. A powerful man, a director or producer or costar, could become a husband or a lover, and serve as a protector. At the same time, as Jane Russell learned from director Howard Hawks on the set of Hughes’s The Outlaw, an actress “needed to learn how to set limits, and enforce them.” Male protection could only go so far. Sometimes, a woman had to defend herself—as Ava Gardner did after a beating from Hughes, by striking him in the face with a heavy bronze ornament. The MGM “fixers,” dispatched to clean up the messes of the studio’s valuable assets, made it clear to Gardner that it was she, not her violent boyfriend, who was in the wrong. But she had her limits, and the fight ended her affair with Hughes.

Hughes’s so-called “womanizing” was at once totally standard for his time, and deeply weird. There were people who said he was impotent, several who thought he was gay, and those who said—like Hepburn—that he was the best lover they ever had. But at some point in the early 1940s, Hughes’s tastes calcified. He no longer wanted stars, or even starlets: He wanted clones. Longworth identifies Russell as Hughes’s “physical ideal” from this point on: “Big breasts, brunette, high drama.” As he got older, his girlfriends stayed the same age. These teenagers rarely got the chance to make a movie, or to establish themselves independently. Hughes would choose them, lure them to Hollywood, sign them to personal contracts, and set them up in a hotel or an apartment where his extensive network of aides and spies would occupy their days and police their nights. It was a perverse kind of wooing that consisted mainly in keeping them waiting, and it’s shocking how many put up with it, as did their parents.

In a patriarchal cattle market, Hughes knew the power of a marriage proposal, and he threw them around like he threw money, proposing relentlessly to most of the women in his orbit, holding out a figurative diamond ring (or often a literal one) as part of a transaction of virginity. The girls had been raised to assume that a proposal was a kind of binding contract, but Hughes, whose entire life was a dance of contracts, knew it was not. He married twice, first to Ella Rice, a Texan heiress, when he was nineteen (whom he shed as soon as he moved to Hollywood to make movies), and late in life to actress Jean Peters, who lived with him only briefly and barely saw him, as he became more and more reclusive.

But he also convinced devout Mormon Terry Moore that a ceremony conducted on a yacht and recorded in a ship’s log was legally binding, mostly so she would sleep with him—and after his death, Moore would devote years to insisting that she had actually married Hughes and was owed a cut of his estate. Hughes spent his life defying the forces—matrimony, taxes, family, gravity—that governed the lives of most ordinary people. Clearly he got off on controlling women, but what that means isn’t quite clear. If a beautiful wife is a trophy, or a “billboard” (as Longworth puts it in her account of the Ava Gardner movie The Barefoot Contessa, which she sees as presenting a version of the actress’s relationship with Hughes), it remains mysterious what victory Hughes wanted to celebrate, or what message he was trying to send.

It makes sense that when Hughes retreated from the world, he went into the movies: renting out screening rooms around town for months at a time, hiring a projectionist to run, over and over again, his favorite movies, with his favorite girls. Even though he owned his own studio, RKO, he spent months in a room on the Samuel Goldwyn lot, until he learned that it had been used by the predominantly black cast of Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess, and abandoned it. His racism, Longworth argues, was tied up with his germophobia; it was a visceral, irrational fear that went far beyond the common prejudices of the time.

Because most people in town respected the sanctity of a movie theater while the film was running, he could hide out from all the people he didn’t want to see: his wife, his other women, his staff, his shareholders. He ate barely anything, swallowed and later injected codeine and Valium, and sat naked in front of a movie screen, taking the hypnotic magic of cinema to its most screwed-up extreme. Something similar happens when we lose ourselves in the story of Howard Hughes—the outside world recedes to a muffled distance. Wars happen and enrich the millionaire further through his manufacturing contracts with the government. American society takes a sharp, stifling turn toward domesticity and conformity in the 1950s and that also benefits him, by confirming his vision of women as the domesticated playthings of powerful men.

There is no doubt some schadenfreude lurking in the fascination with Hughes, as there is in any story about a powerful man’s slow slide out of public life into a private hell of his own making. The legend that lingers in American culture, and the version portrayed by DiCaprio, is of “eccentricity” grown unmanageable, as Hughes barricaded himself first in studio screening rooms, then hotel suites, for weeks and months at a time. His hair and fingernails grew long and filthy, he touched nothing without a protective Kleenex, and grew dependent on painkillers. Throughout the 1960s until his death in 1976, he moved between the Bahamas, Nicaragua, Las Vegas, and other American cities, between hotels that he would sometimes buy to ensure his privacy. An entourage of staff insulated him from the world. The man retreated into myth.

It is tempting to shuffle possible, posthumous diagnoses of Hughes, whether they’re cultural or medical: head trauma from one too many plane crashes; undiagnosed epilepsy (perhaps the cause of all those crashes); secret syphilis; that hypochondriac mother. But as Longworth makes clear, a focus on “what went wrong” in his later years requires that we see the younger Hughes as basically decent and healthy—and it’s only possible to do that if we think it’s really no big deal to scout young women as though the entire world is a catalog, and then, essentially, to purchase and imprison them. In other words, if we celebrate megalomania and gilded male privilege run amok as quintessential American values.

Hollywood’s post-Weinstein reckoning with the entertainment industry’s treatment of women suggests that those values can be questioned. Longworth’s essential book reclaims the narrative from a man who obsessively sought to control it and from the many other men who benefited. She reminds us that abuses of power might be common, but they should not be routine. Instead, they need to be called out and protested, over and over again. Listening to women is a start.