What was your signature like at eighteen? Is it still the same? In the wake of the 2018 midterms, the American electoral system is under scrutiny again—as, in fact, it seems to be almost every two years now. This year, razor-thin margins in Florida and Georgia are drawing fresh attention to allegations of voter suppression and incidents of electoral mismanagement. And now, the recount in Florida has given absentee voters until Saturday to make sure that ballots originally thrown away are counted.

Florida, Georgia, and Rhode Island are three out of several states still requiring a signature match for absentee voters. In practice, what that means is letting election officials check the signature somewhere on the absentee ballot against the signature on an application or a form of government ID. Over the past year, judges in California and New Hampshire have struck down the requirements, declaring they unconstitutionally deprived voters of their right to cast a ballot and have it counted. The process’ implementation in other states is also raising alarms. Among other problems, the policy places a disproportionate burden on voters with disabilities, elderly voters, and others. It’s also strikingly unnecessary and unscientific.

It’s reasonable to try to make sure that the person who casts an absentee ballot is the same person who applied for it. One doesn’t need to be a handwriting expert, though, to see why signature-match laws could be problematic. A person’s signature often changes throughout their life, and in hasty circumstances a well-crafted one can be abandoned in lieu of a scrawled scribble. When it comes to electronic signature pads, all bets are off—as anyone who’s ever seen their own baffling jottings on one of those devices well knows. Nonetheless, Florida election officials use signatures taken from those pads while at the state department of motor vehicles as the basis for comparison to a print signature on Election Day.

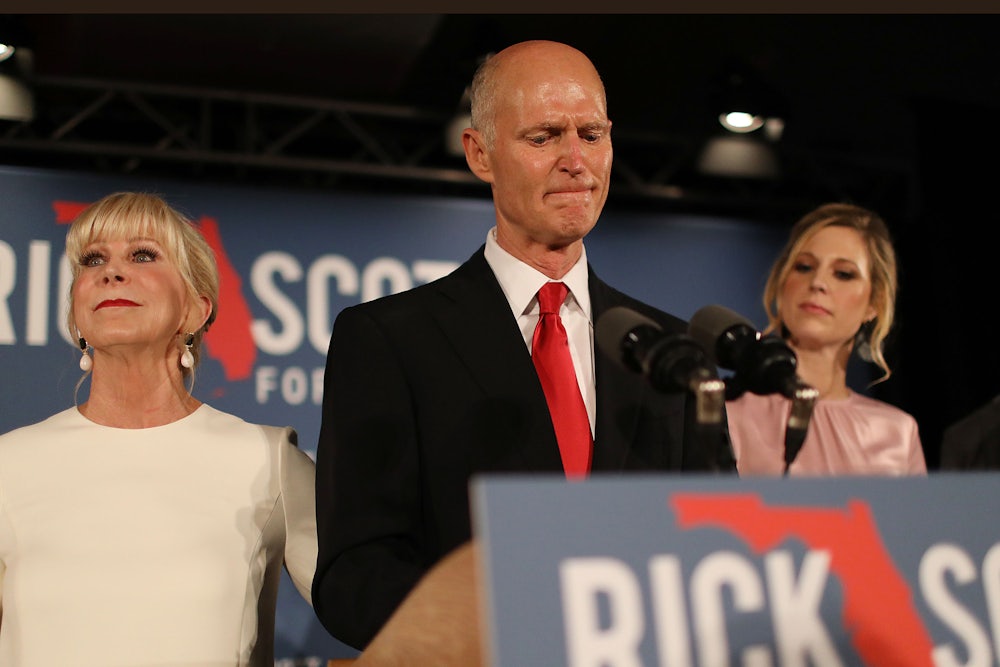

Their determinations could have an impact on two major races. Florida Governor Rick Scott is ahead by a narrow margin in his battle to unseat Senator Bill Nelson, with just over 12,000 votes separating the candidates. State officials are conducting a manual recount in the Senate race, giving voters until Saturday to fix their mismatched signatures—a hurdle they shouldn’t have to cross in the first place.

It’s not immediately clear how nationally widespread the problem is. America’s balkanized election system has some benefits. The lack of any centralized structures makes it somewhat resistant to large-scale rigging, for example. But there are also drawbacks. It’s not immediately apparent how many states use signature-matching laws. There can also be significant differences in how the laws are implemented from state to state. What seems clearer is that the requirements run the risk of tossing out valid, legitimately cast votes.

In New Hampshire, for example, absentee ballots are scrutinized by a local official known as a moderator, who is elected for a two-year term and operates independently from the secretary of state’s office—the office in New Hampshire (and most states) that oversees elections. On Election Day, the moderator publicly (i.e. in front of witnesses and reporters) checks the signature on the absentee ballot envelope—which in New Hampshire is a piece of paper doubling as an affidavit, with the actual ballot and vote inside. If he or she thinks it doesn’t match the one on the application form for the absentee ballot, the envelope is left unopened and the ballot isn’t counted. Their decision effectively nullifies that person’s vote.

The American Civil Liberties Union challenged the state’s law in 2017 on behalf of three New Hampshire voters who were disenfranchised during the 2016 election. One of them, Mary Saucedo, was 94 years old at the time. Advanced macular degeneration has left Saucedo legally blind, and she told the court that she filled out her ballot with the assistance of her 86-year-old husband. He filled out the absentee ballot request form on her behalf, and when her signature on the envelope didn’t match the one on the form, it was rejected on Election Day.

“There is no procedure by which a voter can contest a moderator’s decision that two signatures do not match, nor are there any additional layers of review of that decision,” Judge Landya McCafferty wrote in her August ruling blocking the law. “In other words, the moderator’s decision is final. Moreover, no formal notice of rejection is sent to the voter after Election Day.” New Hampshire voters whose absentee ballots are rejected can only find out by checking the secretary of state’s website after voting has already concluded. The site removes the information after three months.

A California state court blocked a similar law earlier this year with relative ease. State officials tried to contend that the provision had only prevented roughly 45,000 voters from casting a ballot, a group larger than the number of seats in San Francisco’s Pac Bell Park. But the judge concluded that it still violates the Constitution’s due-process requirements because it did not give those affected a chance to respond.

“The statute fails to provide for notice that a voter is being disenfranchised and/or an opportunity for the voter to be heard,” Judge Richard Ulmer wrote in his ruling. “These are fundamental rights. The parties consume considerable ink disputing what test to use in determining unconstitutionality, but [the provision] does not pass any test cited.”

In Georgia, the epicenter of voting-related controversies this election cycle, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order in October that barred state officials from tossing out ballots with signature mismatches. Instead, they became categorized as provisional ballots. The court ordered that voters be given notice that their ballot was being questioned as well as an opportunity to quickly remedy the problem in person after Election Day. A Washington Post analysis published on Friday found that the bulk of the statewide rejections are coming from a single Georgia county, which may suggest that state laws are being enforced unevenly.

Florida may be the most dramatic example of all. Tens of thousands of ballots in the state are in bureaucratic purgatory at the moment thanks to the state’s signature-match requirements. The impact is particularly acute in Florida because its elections are often decided by extremely close margins. Though the state’s 2018 results aren’t yet finalized, fewer than a hundred thousand votes have separated the first- and second-place candidates in both the Florida governor’s race and the U.S. Senate seat race in recent days.

This problem isn’t new for the state, either. According to Mother Jones, Florida officials rejected 24,000 ballots in 2012 and 28,000 ballots in 2016 for purportedly mismatched signatures. (Since the state is still undergoing a manual recount, it’s unclear how many ballots will ultimately be rejected this cycle.) The state offers voters the opportunity to “cure” the problem by showing up in person at state election offices to correct any errors, but the magazine reported that younger and minority voters were less likely to follow through on those offers.

Signature-match laws fall within a broader spectrum of measures that can deprive voters, based on small errors, of their electoral influence. Under Secretary of State Brian Kemp, Georgia tried to freeze voter-registration applications if they did not precisely match state databases, even if the difference was a mere comma or hyphen. A state judge also ordered Georgia earlier this week to not certify its election results until it counts ballots that had been excluded because the voter did not list his or her date of birth. Stringent measures like these are often justified by supporters as being necessary to thwart voter fraud, which is virtually nonexistent. Their practical impact appears to be disproportionately excluding lower-income voters or those from disadvantaged communities, who may lack the resources to contest their disenfranchisement.

Most of the discussion surrounding the integrity of the voting process this year focused on figures like Kemp and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach—both of whom have been accused of voter suppression—or on sweeping measures like voting-roll purges or voter ID laws. But voter rights aren’t always denied by heavy-handed tactics or blatantly discriminatory laws. Sometimes the most insidious threat to the franchise comes from a thousand bureaucratic cuts.