In early 2011, when new census figures showed that Evergreen, Alabama, a small city midway between Montgomery and Mobile, had grown from 53 to 62 percent black over the previous ten years, the white majority on the city council took steps to maintain its political dominance. They redrew precinct lines, pushing almost all the city’s black voters into two city council districts. Then, election administrators used utility information to purge roughly 500 registered black voters from the rolls, all but ensuring that whites would maintain their majority on the council and keep control of Evergreen.

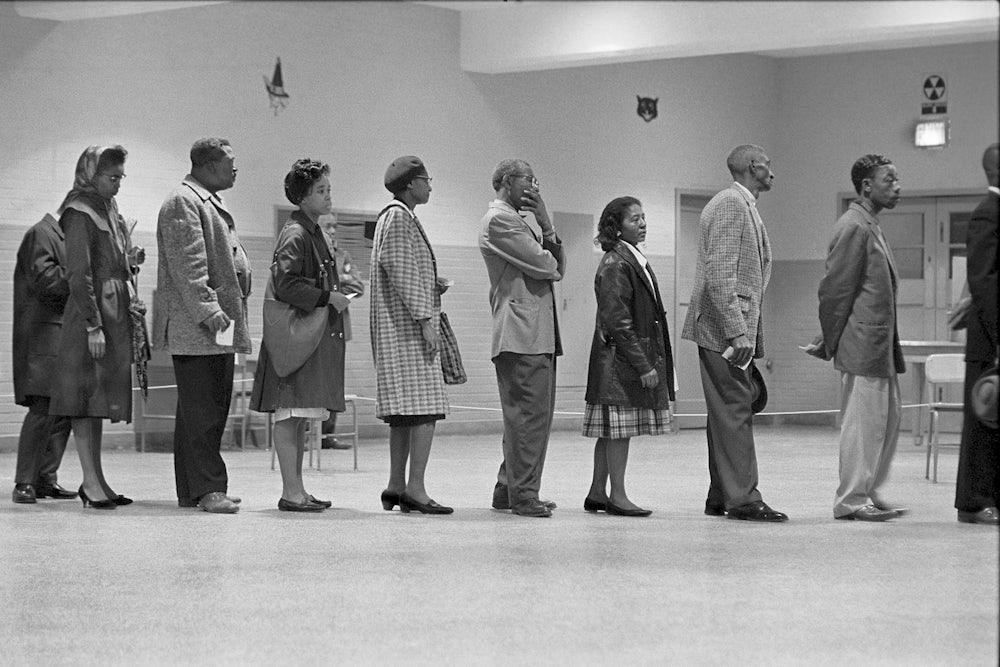

That kind of voter suppression is exactly what the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed to prevent. For 48 years, its “preclearance” provision barred election officials in states with histories of voter suppression from making changes to election procedures without permission from the federal government. It was far from a perfect system—even with preclearance in place, Evergreen officials were able to purge the rolls—but it did help hundreds of thousands of black Southerners vote. By 1972, black registration rates had reached 50 percent in all but a few Southern states. In 2013, however, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, striking down the provisions of the law that defined which states fell under preclearance.

Since then, efforts to keep people from voting have intensified. Officials in three states have shrunk early voting time lines, and one eliminated same-day registration. Five have implemented new voter ID laws. In Texas, someone can now vote with a handgun license but not a student ID. Georgia forces voters to use the same name on their application as the one on their ID card; something as trivial as an errant or missing hyphen, a dropped middle name, or the inclusion of an extra initial on an application could prevent someone from voting. (That was how Georgia’s Secretary of State and then–Republican gubernatorial candidate Brian Kemp was able to block, if only temporarily, some 53,000 voter registrations, mostly from African Americans.) This year, South Dakota has said people must have a street address to cast a ballot, disenfranchising many Native Americans who, because they live on reservations, only have post office boxes. And just weeks before the midterms, reporters in Dodge City, Kansas, which has a growing Latino population, discovered that election officials gave newly registered voters the wrong polling site address. (The real location was outside of town, a mile from the nearest bus stop.) All told, voters in 23 states faced greater obstacles at their polling places than they did in the midterms eight years ago, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. (There are occasional, if rare, successes. In 2014, for example, citizens of Evergreen were able to bring the city back under federal control after 14 months in federal court.)

It’s time Democrats think seriously about restoring some of the provisions lost to Shelby. If there is one lesson to draw from the midterms, it’s that the right to vote is a partisan issue. Suppression, framed as election security or a last defense against voter fraud, has become a fundamental tactic of Republican efforts to exhaust, confuse, and disqualify Democratic voters—and to win elections. Democrats must fight for access to the ballot for all citizens, and for the federal oversight necessary to assure it. The new Democratic majority in the House cannot be otherwise sustained.

Such a bill would have to accomplish a few things: In 2013, the Supreme Court’s conservative justices ruled that the Voting Rights Act unfairly singled out states for federal control because they had histories of discriminatory voting practices. But Democrats can sidestep those concerns by drafting new criteria to determine which jurisdictions have to submit to federal oversight. If, say, the share of citizens registered to vote drops suddenly, or the portion of registered voters who participate in elections goes below a certain point, that might be cause to bring a jurisdiction under federal control. It wouldn’t matter whether the state had a history of discrimination; any state, no matter where it was, could be put under federal oversight so long as there were indications that discrimination was taking place now. Congress might also mandate that any voting law, like a strict voter ID requirement, that has historically prevented people of color from voting be proposed first to the federal government before it’s implemented.

“Republicans love voter ID; they think it is great,” said Charles S. Bullock III, co-author of The Rise and Fall of the Voting Rights Act. “But photo ID has also worked for Democrats, in a different way. Try to restrain the right to vote from anyone, and voting becomes the most important thing in the world. It’s basic human nature.”

That should aid Democrats in their push to find the votes to pass such a bill. Of course, the chances of President Donald Trump signing one into law are remote. But a few Republicans in the Senate, eager to defend American ideals, might be willing to support it. After all, the more time and energy they commit to voter suppression, the more their party exposes its uneasiness with representative democracy.