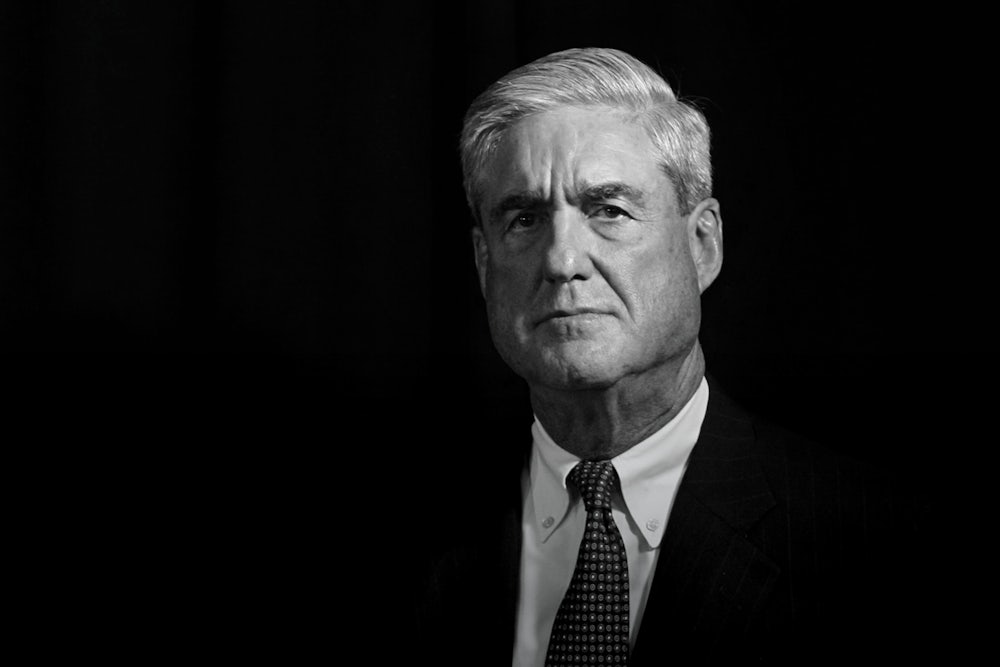

Here’s what the post-midterms world might look like: Democrats control the House by a decent margin. But they pick up just one seat in the Senate, allowing Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to exploit that more powerful legislative body to guard the White House. (Both electoral outcomes are likely, according to predictions.) Then, before special counsel Robert Mueller has the chance to reveal any of the work his team has been quietly doing during the campaign season, President Donald Trump finds a way to end or severely curtail Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Trump’s boldest move would be to fire Mueller himself. Shortly after Mueller was appointed in May 2017, Trump’s team claimed that the special counsel had conflicts of interest—claims that Trump might use to justify firing him. More recently, Trump has complained that the investigation—which by special counsel standards has barely begun—has gone on too long. If Trump is planning on firing Mueller, he’s most likely to do it right after the election, since it will take two months before the new Congress is sworn in and any political consequences will be delayed.

If Trump does not want to fire Mueller directly, he could derail the investigation in a couple ways. He could replace Mueller’s supervisor, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein. Rosenstein has forced Mueller to spin off unrelated parts of the investigation, but for the most part has permitted Mueller to proceed as he wishes, much to the chagrin of the White House. If Rosenstein were fired and no other staff shake-ups were made, his automatic replacement would likely be Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who has previously accused the FBI of overreach and claimed that former FBI Director James Comey, who was fired by Trump over the Russia affair, had shielded Hillary Clinton from possible prosecution. Democrats worry that an empowered Francisco could fire Mueller himself.

Alternately, Trump could convince Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has recused himself from the Russia investigation, to resign. Trump could replace him immediately with either Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar or Department of Transportation General Counsel Steven Bradbury, both Senate-approved officials who could take over temporarily under the Vacancies Reform Act. Both are reportedly under consideration to replace Sessions; both could fire Mueller if named attorney general.

Finally, Trump might even carry out a Wednesday Morning Massacre, working his way through the Department of Justice until someone decides they’ll back a claim that Mueller has engaged in misconduct—then use that accusation to justify firing him directly.

That would leave the new Democratic majority in the House as the chief means of carrying on the Mueller investigation. What could Democrats actually accomplish?

There are three main elements to a Mueller-less Russia investigation: 1) what Democrats could investigate whether or not Mueller is fired; 2) what they would be missing if Mueller were to be axed; and 3) what Democrats can salvage from an aborted investigation. Let’s take them in turn.

Democrats can call a whole lot of witnesses.

In a recent op-ed in The Washington Post, Rep. Adam Schiff of California promised that if he were to become chair of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence under a Democratic majority, the committee would provide “a full accounting” of Russia’s entanglements with the Trump campaign and Trump White House.

He said the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, under Rep. Elijah Cummings’s leadership, would address how Trump “is profiting off the presidency,” indicating that that committee would investigate Trump’s possible violation of the Emoluments Clause, which prohibits the president from receiving payments from foreign governments. These payments may include those made to Trump’s inauguration committee, some of which came from Russian donors.

Schiff also suggested that the House Judiciary Committee would focus on “potential abuse of the pardon power [and] attacks on the rule of law,” which could include Trump’s daily attacks on the FBI, his tampering in FBI investigations, and the pardons he reportedly floated to his former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn and one-time campaign chief Paul Manafort, before both entered plea agreements and started cooperating with Mueller.

Schiff suggested his own committee would examine Russian financial influence over the president, which could cover Trump’s various business dealings in Russia. But it’s also likely that the Financial Services Committee, under Rep. Maxine Waters of California, would conduct much of that work.

In March, Schiff and the other Democrats on the Intelligence Committee released a status report naming witnesses Republicans had refused to call in their own cursory probes into Russia’s ties to the White House. These witnesses included White House aides Stephen Miller and Keith Kellogg, as well as former administration officials like former Chief of Staff Reince Priebus and K.T. McFarland, who served under Flynn.

Between them, these witnesses could provide more insight into the Trump campaign’s interest in pursuing a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, as well as into whether Russians were offering stolen emails from the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee in exchange for such meetings. The witnesses could also shed light on Trump’s personal involvement in Mike Flynn’s reassurances to Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, during the presidential transition in December 2016, that the Trump administration would seek to reverse Obama-era sanctions on Russia.

Schiff said he could also call Roman Beniaminov, who worked with Rob Goldstone, the music promoter who first set up the Trump Tower meeting in June 2016 in which Donald Trump Jr. sought to obtain dirt on Hillary Clinton. Beniaminov learned in advance that Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya would be dealing “some negative information” on Clinton.

Democrats would also call witnesses related to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which the Trump-affiliated firm gained access to the data of millions of Facebook users. Those witnesses could provide insight into how the Trump campaign exploited Facebook’s personal data to suppress certain kinds of voters in 2016. The legal concern here is two-fold: first, whether Cambridge Analytica employees from the U.K. worked for Trump illegally in the United States; second, whether Trump’s PAC, where some of those employees worked, coordinated improperly with the campaign. Given reports that Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix had discussions with billionaire Trump supporter Rebekah Mercer about optimizing the release of the emails stolen by Russia, Democrats would also inquire whether Cambridge Analytica exploited data stolen by Russians.

Perhaps the most incendiary testimony could relate to how Russians Aleksandr Torshin and Maria Butina, with the assistance of Republican operative Paul Erickson, used the National Rifle Association as a vehicle to draw the Republican Party closer to Russia. While Butina was arrested in July and Erickson is reportedly under active investigation, court documents relating to Butina’s prosecution describe Rockefeller heir George O’Neill Jr.’s active cooperation in Butina’s operation, down to his learning about Putin’s personal approval for the effort to host a series of “friendship and dialogue dinners” at which Russians could foster pro-Russian policies. “[A]ll that we needed is <<yes>> from Putin’s side. The rest is easier,” Butina wrote O’Neill in March 2016.

In the March plan, Democrats also said they would compel more information and testimony from witnesses that Republicans had let off easy. For example, the report lays out how both Donald Trump Jr. and Trump’s former campaign chair Corey Lewandowski refused, in past appearances before the Intelligence Committee, to describe communications pertaining to the June 9 meeting in Trump Tower.

The report also calls for more materials from the president’s former lawyer Michael Cohen pertaining to a 2016 bid to brand a Trump Tower in Moscow that continued well into the election year. And it argues that Erik Prince, the former head of the private security firm formerly known as Blackwater, must fully explain his meeting in the Seychelles with the head of a Russian investment firm, Kirill Dmitriev. Reporting since Prince testified to the committee in November 2017 suggests Prince lied about the meeting being an effort to set up a backchannel between Trump’s team and Russia.

Democrats have also promised to subpoena Twitter, WhatsApp, Apple, and the Trump Organization to learn more about communications that might be part of a conspiracy. For example, they’d like to obtain records showing which people, including Trump associates, communicated with Russian military intelligence mouthpiece Guccifer 2.0 or WikiLeaks, the outlets that released the Clinton and DNC emails stolen by Russia. In addition, Democrats would like to learn whether Trump associates communicated using encrypted messaging applications—messages that might have been missed in prior records requests.

So Democrats have a fairly robust plan for the investigations they’ll conduct if they win a majority in the House. But even that would only scratch the surface.

Democrats don’t have Mueller’s investigative prowess.

The steps laid out by Schiff don’t account for what happens if Mueller is fired before finishing his investigation. That’s a problem because, at every step of his probe, Mueller has identified key players in Russia’s 2016 election operation that no one, including members of Congress, had yet discovered.

A few examples: A rural California man, Richard Pinedo, sold Russian internet trolls the identities they used to sow division among voters on Twitter and Facebook during the election—a role only disclosed when Mueller indicted the Internet Research Agency, a Russian troll farm based in Saint Petersburg. That same indictment described, but did not name, three Trump campaign officials in Florida who interacted with Russian trolls organizing a “Florida Goes Trump” rally in August 2016. (Those three people have never been publicly identified, and if they’ve been interviewed by any congressional committee, that fact remains secret.)

Meanwhile, Sam Patten, a Republican lobbyist, started cooperating with federal prosecutors a good three months before it was publicly reported. Patten was the partner of the Russian-Ukrainian consultant and suspected Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik, who interacted with Paul Manafort during the Trump campaign.

The most visible signs of Mueller’s investigation since February pertain to longtime Trump hatchet man Roger Stone, and yet where that aspect of the probe might lead remains a mystery. Trump campaign aide Sam Nunberg, Stone assistant John Kakanis, Stone social media adviser Jason Sullivan, Stone associate Kristin Davis, radio host Randy Credico, and conspiracy theorist Jerome Corsi—all appeared before Mueller’s grand jury.

Mueller’s team also interviewed Ted Malloch, an associate of the British anti-immigration firebrand Nigel Farage. They questioned Trump aide Michael Caputo, while Stone aide Andrew Miller is currently fighting a grand jury subpoena in the District of Columbia Circuit Court. By May 25, at a time when just four of his associates had publicly revealed their testimony, Stone said eight of his associates had already been contacted by Mueller’s team. (Another witness against Stone received a subpoena but has never been publicly identified.)

While public reports have focused on questions about Stone’s interactions with Guccifer 2.0 or WikiLeaks, some of the Mueller team’s activity may relate to Stone’s dirty election tricks, which were funded by dark money groups. It’s unclear how such fundraising might relate to allegations that Stone cooperated with Russia. So even for the part of the Mueller investigation that has been most public, there are big gaps in the public record—gaps that committees in the House might not be able to close.

And that’s just witnesses. Mueller has also obtained a great deal of records and communications that no committee in Congress is known to have obtained. As one example, on March 9, Mueller obtained search warrants for five AT&T phones, having shown probable cause those phones included evidence of a crime. At least one of those phones belonged to Paul Manafort (which is how details of the warrant became public), but the identities of the other people who had their phones searched remain undisclosed.

Then there’s the money angle. Buzzfeed has done great reporting on Suspicious Activity Reports on bank transfers associated with the Russian investigation. It has also raised questions about whether Treasury has cooperated with the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the one committee that requested financial records relating to the investigation. But there’s no sign any committee in Congress has examined Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency transfers—financial flows that have figured prominently in Russia’s campaign disruption efforts. If the Mueller investigation is sidelined, congressional investigators might need to access the secret connections Mueller’s team has spent 18 months discovering.

How would they go about doing that?

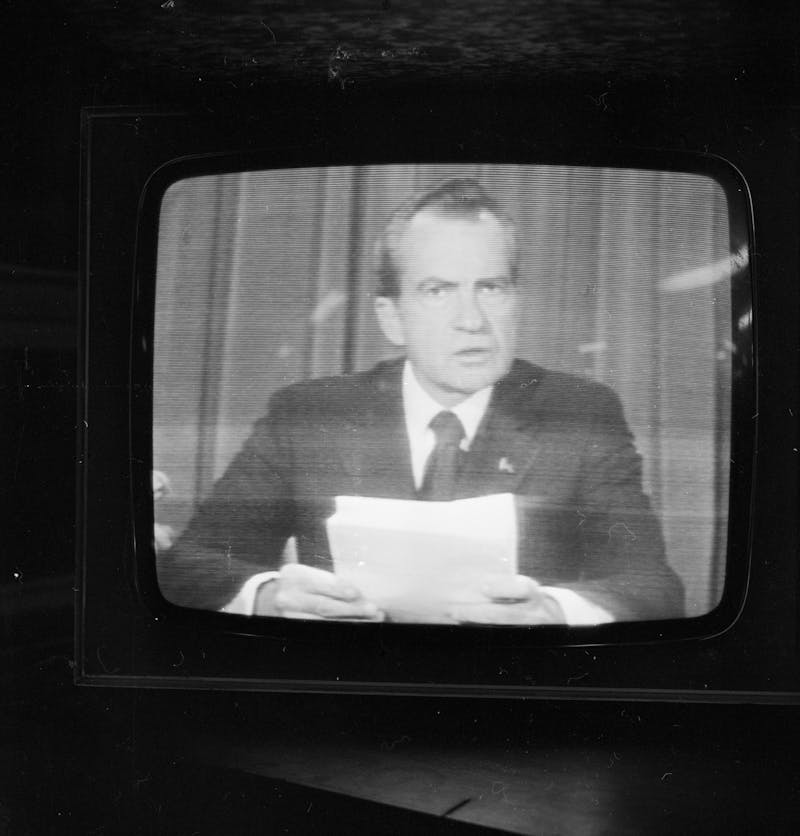

Democrats can use a Watergate playbook.

House Democrats might follow the precedent set during Watergate—the last time that a president tried to thwart an investigation into election corruption by firing the Department of Justice officials conducting it.

Mueller’s activities thus far have been laid out in plea deals and highly detailed “speaking” indictments, which provide far more information about the actions involved than strictly necessary for legal purposes. But according to the regulation that governs his appointment, at the end of his investigation Mueller must also provide the attorney general with “a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the special counsel.” Also upon completion of the investigation, if the attorney general overrules an action Mueller wanted to take, he or she must notify the chair and ranking members of the Judiciary Committee.

It’s not clear what, within the scope of the regulations, would happen to such a report in the scenario laid out here, where Mueller got fired on some trumped-up claim of improper action. The only thing that would necessarily get shared with Congress is the report on why the attorney general had overruled Mueller, which wouldn’t necessarily include details of what else Mueller had discovered. Indeed, Neal Katyal, the former Obama administration lawyer who wrote the special counsel regulation under which Mueller operates, recently advised Rosenstein to provide a report to Congress before a meeting with Trump at which he might have been fired.

But Rosenstein might not permit such reports under department regulations. Rosenstein has refused to share information on the investigation in the past, citing the Department of Justice policy on not confirming names of those being investigated unless they are charged. And thus far, even Republicans attempting to undermine the investigation have not sought investigative materials from Mueller, instead focusing on the FBI investigation up to the time when Mueller was hired on May 17, 2017. That’s partly because under rule 6(e) of grand jury proceedings, information can only be shared for other legal proceedings (such as a state trial or military commission).

Yet a Watergate precedent suggests the House could obtain the report if Mueller were fired.

Some Freedom of Information Act requests have recently focused attention on—and may lead to the public release of—a report similar to the one Mueller is mandated to complete. It was the report done by Watergate prosecutor Leon Jaworski, referred to as the “Road Map.” The Road Map consists of a summary and 53 pages of evidentiary descriptions, each citing the underlying grand jury source for that evidentiary description. In 1974, Jaworski used it to transmit information discovered during his grand jury investigation to the House Judiciary Committee—which then used the report to kickstart its impeachment investigation.

Before Jaworski shared the Road Map, however, he obtained authorization from then-Chief Judge John Sirica of the D.C. Circuit Court. In Sirica’s opinion authorizing the transfer, he deemed the report to be material to House Judiciary Committee duties. He further laid out how such a report should be written to avoid separation of powers issues. The report as compiled by Jaworski offered “no accusatory conclusions” nor “substitute[s] for indictments where indictments might properly issue.” It didn’t tell Congress what to do with the information. Rather it was “a simple and straightforward compilation of information gathered by the Grand Jury, and no more.” Per Sirica, that rendered the report constitutionally appropriate to share with another branch of government.

If Mueller—whose team includes former Watergate prosecutor James Quarles—were fired and he leaves any report behind that fits the standards laid out here, this Watergate precedent should ensure it could be legally shared with the House Judiciary Committee.

Can Trump do anything to stop them?

The D.C. Circuit Court recently heard a case, McKeevy v. Sessions, on whether judges can release historic grand jury materials. Chief Judge Beryl Howell, who is presiding over the Road Map FOIAs as well as the Mueller grand jury, has stayed the Road Map FOIA to await its results. But McKeevy is a request for public release of grand jury materials, rather than disclosure to a government body with the constitutional duty to conduct its own investigations. As such, it probably wouldn’t affect the Watergate precedent.

So if Trump challenges the conveyance of Mueller’s report to the House Judiciary Committee, he would be making an argument not even Richard Nixon made. It is also an argument that the U.S. v. Nixon precedent—which held that due process limits the president’s claims of privilege—likely would not support.

Still, Trump will have one more way to stall, though probably not kill, House efforts to pick up where a fired Mueller left off. Under current House rules, committee chairs have the authority and the majority votes to issue subpoenas; if Democrats win a majority, they could even set new rules in the new Congress permitting committee chairs to issue subpoenas by themselves. But because the Department of Justice traditionally enforces subpoenas, congressional committees led by the opposition party have traditionally struggled to enforce subpoenas they do issue, especially for White House officials. That would be doubly true if Trump replaced Sessions with someone even more interested in obstructing real accountability for the president.

Even under Republican control of Congress, Trump officials have avoided or sharply limited their testimony by suggesting executive privilege might cover their testimony—without actually making Trump invoke it. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats and then-Director of National Security Agency Mike Rogers dodged testimony in this fashion, before ultimately testifying in a session closed to the public. More egregiously, former White House Communications Director Hope Hicks and Lewandowski refused to answer some of the questions posed by the House Intelligence Committee, notably declining to share information on the presidential transition.

Given two recent precedents—forcing the testimony of George Bush’s White House Counsel Harriet Miers (and consigliere Karl Rove) in the investigation into the firing of U.S. Attorneys and the cooperation of Barack Obama’s Attorney General Eric Holder in the investigation into the Fast and Furious scandal—a Democratic House will likely be able to compel cooperation from witnesses, even if it might take a while.

At a fundraiser in July, Rep. Devin Nunes, the Republican who thwarted all of Schiff’s investigative ambition on the House Intelligence Committee, explained that unless the Russian investigation were stopped, then the only way to thwart it would be for Republicans to retain the majority in the House. “We have to keep the majority,” he said. “If we do not keep the majority, all of this goes away.”

It might take time and a whole lot of litigation for the Mueller investigation to come to light. But Nunes may well prove to be right.