Every state routinely prunes its voter rolls when registered voters move, die, or get convicted of a felony. But under Secretary of State Jon Husted, Ohio has taken an aggressive tack to removing voters from state registration lists. The state purged more than two million voters from its rolls between 2011 and 2016. Many, if not most of those voters were likely ineligible. But over the past few years, as part of an annual audit of sorts, Husted’s office has removed thousands of eligible voters from the rolls simply because they failed to vote in three consecutive elections and didn’t return a postcard confirming their registration.

Critics, including state Representative Kathleen Clyde, said this practice disproportionately affects low-income Ohioans and communities of color, two constituencies that typically favor Democratic candidates. In 2015, Clyde introduced a bill to block Husted from purging voters unless they leave the state. Two years later, she authored another bill that would enact automatic voter registration.

Neither measure became law in the Republican-led chamber. And this past June, the Supreme Court upheld Husted’s purge. But soon Clyde may be in a position to stop the practice herself: She’s the Democratic nominee to replace Husted as secretary of state, a position that would give her significant influence over the state’s election laws.

Clyde is one of roughly a dozen Democratic candidates across the country who could become their states’ chief election officers if a blue wave sweeps through polling places in November. Their victories would provide Democrats an opportunity to turn back voter suppression efforts by Republican officeholders—and could give the party a leg up in voter turnout when President Donald Trump is up for reelection in 2020.

Forty-seven states have a secretary of state, either as an appointed post or an elected office. While the position’s duties can vary from state to state, the most common duty is to oversee elections and voting procedures, which are shaped by a mixture of federal statutes, state laws, and county policies. Navigating that legal labyrinth often falls to secretaries of state—the hall monitor, of sorts, for the nation’s democratic processes.

The role has taken on a heightened significance in recent years. Republicans hold more than half of the positions across the country, giving the party an advantage when shaping the nation’s election processes. Some Republican secretaries of state have used the position to crusade against the purported threat of voter fraud. Though vanishingly rare in the U.S., voter fraud has provided a useful justification for more restrictive voting measures that have kept tens of thousands of Americans from exercising their right to cast a ballot.

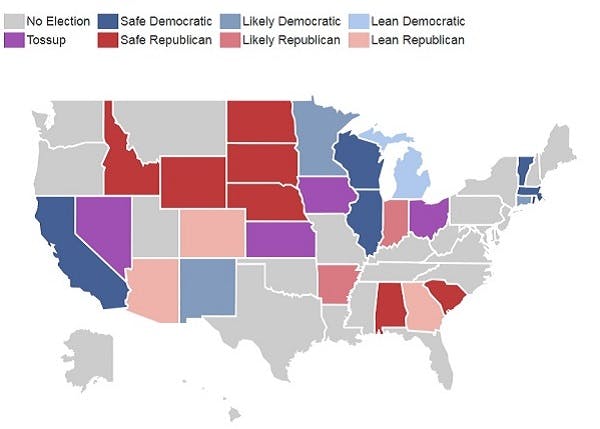

Democrats have an opportunity in the November midterm elections to tear down those barriers. Roughly two-thirds of the nation’s elected secretary of state positions are on the ballot this year, and Republicans are defending seven open seats, versus none for Democrats. (Governing magazine has rated eight races as competitive—and all seats currently held by Republicans.) What’s more, the secretaries of state elected this year will serve during the 2020 presidential election, meaning that Democratic officeholders would be well-placed to expand voter access in battleground states like Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, and Wisconsin should they prevail in two weeks.

Some contests have already drawn national attention. Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, the Republican candidate for governor, froze 53,000 voter registration forms for dubious reasons, according to an Associated Press investigation earlier this month. More than 70 percent of the forms came from black applicants, raising concerns that the freeze is aimed at reducing voter turnout for Stacey Abrams, Kemp’s Democratic opponent. (If elected, Abrams would be the first black woman governor in American history.) Kemp also presided over a sweeping purge of the state’s voter rolls that removed almost 700,000 voters over the past two years.

Brad Raffensperger, the Republican candidate to replace Kemp, said at a debate earlier this month that he would continue the purges to “safeguard and keep our elections clean.” Jack Barrow, the Democratic challenger, opposes them. “Just because the Supreme Court allows you to discriminate doesn’t mean you must discriminate,” he wrote on Twitter after the court’s ruling in the Ohio case. “As your next Secretary of State, I’ll protect citizens who choose not to vote and keep them from being purged from voter rolls.” Barrow has also been critical of Kemp’s approach to election cybersecurity after Russian hackers targeted state election systems in 2016.

Kansas also moved to the center of the voting-rights wars after Kris Kobach’s election as secretary of state in 2010. He became a national spokesman of sorts for restrictive voting laws, championing the state’s strict voter ID law, successfully persuading Kansas lawmakers to let his office prosecute voter-fraud cases, and overseeing a dubious interstate anti-fraud program with a high false positive rate. His efforts to add a proof-of-citizenship requirement to the state’s voter registration forms sparked a legal showdown with the ACLU, which successfully argued in court that the move violated federal election law. A federal judge found Kobach in contempt earlier this year for failing to register voters who had been previously blocked by the requirement. Kobach is leaving the secretary of state post because he’s running for governor (and facing a strong challenge from Democratic state Senator Laura Kelly, who backed his voter citizenship bill).

It’s hard to imagine a sharper contrast to Kobach than Brian McClendon, the Democratic candidate to replace him. A former Google vice president who helped build Google Earth, McClendon is one of multiple Democrats running for secretary of state offices who have emphasized election cybersecurity. He’s also sketched out a less centralized version of the Kansas secretary of state’s office that focuses on voter access. “With appropriate leadership and support from the state, county elections staff are admirably effective at managing voting rolls,” he told the Topeka Capital-Journal in June. “And the office of the attorney general is better staffed and better qualified to handle law enforcement and prosecutions in the rare instances of voter fraud.”

Not every Republican secretary of state has tried to suppress voter participation, and not every Democratic candidate will have the power to carry out sweeping changes if they win next month. Some races, in fact, are referendums on expanding voter access rather than suppressing it: Michigan’s secretary of state contest is taking place alongside a major ballot initiative that would enact automatic voter registration, Election Day registration, no-excuse absentee ballots, and a slate of other reforms. Jocelyn Benson, the Democratic candidate, supports the initiative, while her Republican opponent Mary Treder Lang does not.

Secretary of state contests haven’t always been high profile or high stakes. But as the Supreme Court abandons its role as a guardian of voting rights, and the Trump administration ramps up its efforts to combat the illusory threat of voter fraud, this once-esoteric position could be a key bulwark in protecting Americans’ right to choose their own political destiny.