Before Angela Merkel decided to welcome more than a million asylum seekers to Germany in 2015, the German conservative coalition she belongs to spent years insisting that “Germany is not an immigration country.” When Merkel’s Christian Democrats fought to restrict the right to asylum in 1993, for example, their Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) one-upped by suggesting that Germany abolish the right to asylum altogether and introduce a state-granted privilege in its stead.

Sunday’s state elections in Bavaria showed how much the country has changed since then. For nearly six decades, the CSU has ruled Bavaria under the mantra that no party should exist to its political right. Paradoxically, this concern about right-wing extremists often served as an excuse for the CSU to adopt a very right-wing agenda.

But with the rise of the intensely nationalist, anti-immigration Alternative für Deutschland, the political landscape has shifted, demanding ever-greater contortions from conservatives eager to keep their voters. This year, the CSU party’s electoral campaign to win over voters flirting with the far right backfired—it was the pro-refugee Green Party which came second in the exit polls and helped cost the CSU its absolute majority, the AfD also gaining seats in the Bavarian parliament for the first time. And the results, possibly alongside the U.S. midterms in November, may soon become an object lesson in the challenges facing traditional conservative parties in the new populist right-wing environment.

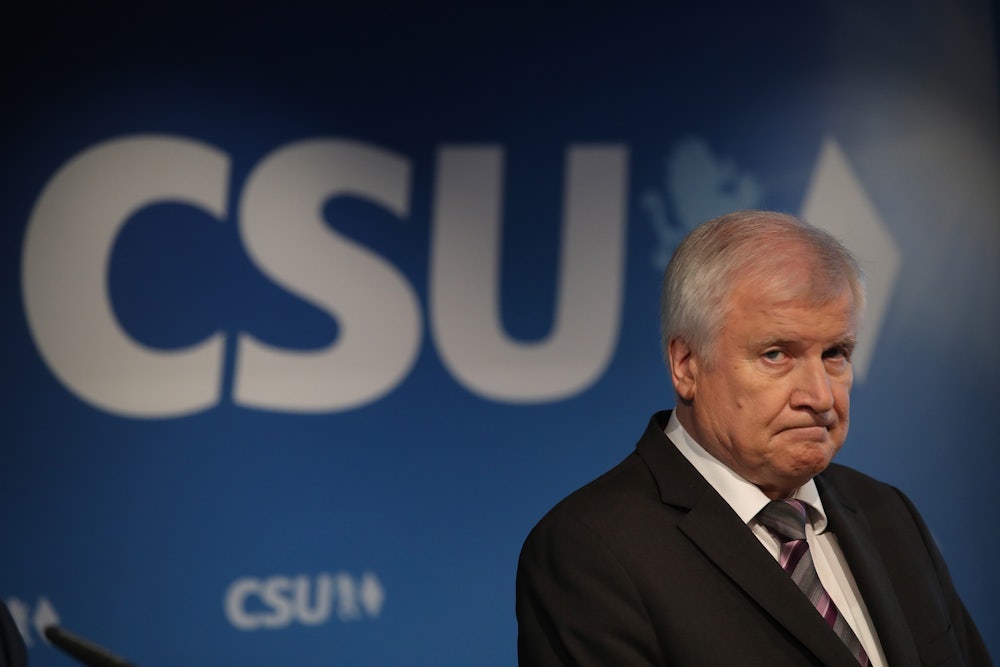

Bavarian Prime Minister Markus Söder of the CSU spent a lot of his summer chatting about “asylum tourism” and “state failure.” He also egged on the CSU party leader Horst Seehofer to challenge Angela Merkel over a symbolic migration policy disagreement to the point that it almost ripped apart her coalition government.

All of this went down well in the beer tents, where CSU party members praised Söder for “showing Germany who is boss.” But the erratic behavior of the CSU party’s leadership this year made many Bavarians—an increasing number of whom come from other parts of Germany and the world—“embarrassed and uncomfortable,“ according Simone Egger, an assistant professor for European ethnology at the University of Munich. In Munich, thousands of people took to the streets throughout the summer to protest “the politics of fear.” Antifa teens walked with churchgoers who held up signs reading “mass instead of hate.”

Religious politics have traditionally favored the CSU in Bavaria—a relatively Catholic state, although the number of churchgoers is declining. But Cardinal Reinhard Marx was unimpressed when Söder, who previously accused the churches involved in asylum aid projects of making a profit from the state, ordered crosses to be hung on all state buildings as a cynical nationalist ploy, calling it a “cultural symbol.” “Those who only see the cross as a cultural symbol have not understood it,” the cardinal said in a rare political intervention, speaking to the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Prior to the 2015 migrant crisis, it was not unusual for Germany’s conservative parties to run election campaigns that stoked Islamophobia and anti-immigration sentiments. But since Angela Merkel decided that Germany is, in fact, an “immigration country,” conservatives have lost their xenophobic credibility with the right-wing fringe. Now, it seems conservatives who try to win those voters back risk alienating the mainstream base, newly conscious of xenophobia’s dangers thanks to the more distilled form on offer with the AfD, or possibly just more attuned to the current multicultural reality.

It appears in this year’s Bavarian state elections that some of the CSU’s voters were appalled by the kind of rhetoric that would have been pretty socially acceptable at a boozy party convention a few years earlier—for example, when party leader Horst Seehofer stood up in a beer tent in 2011 and assured his fold that Merkel’s coalition government would stop “immigration into the social security systems,” up “until the last bullet.”

It’s also possible voters were put off purely by the disorder and disconnect between Merkel and the local conservative leaders. But between the protests and the cardinal’s rare foray into politics, there’s reason to think at least some of the desertion came from moral grounds. Stephan Reichel works on coordinating church asylum for rejected asylum applicants. In 2015, he noticed how many of the traditional Christian clubs in the Bavarian countryside became active again through asylum aid programs. But since then, the CSU government’s restrictive policies, which were intended to ward off conservative backlash to Merkel’s open-door refugee policy, have made it more difficult for these groups to help refugees integrate. Now, Reichel tries to connect the church communities and lobby for their new political interests. Many people he meets used to vote for the CSU.

As both the AfD and the Greens make gains in Bavaria, it’s clear the refugee crisis galvanized voters—just not always in predictable ways. The CSU’s loss of its sixty-one-year majority could be seen as a special German case, a reflection of Merkel’s unusual leadership on refugees. But it also shows that for mainstream conservative parties—caught between xenophobes who have adopted their rhetoric and a newly enraged left—coopting the far right’s agenda is no longer the political panacea it once was.