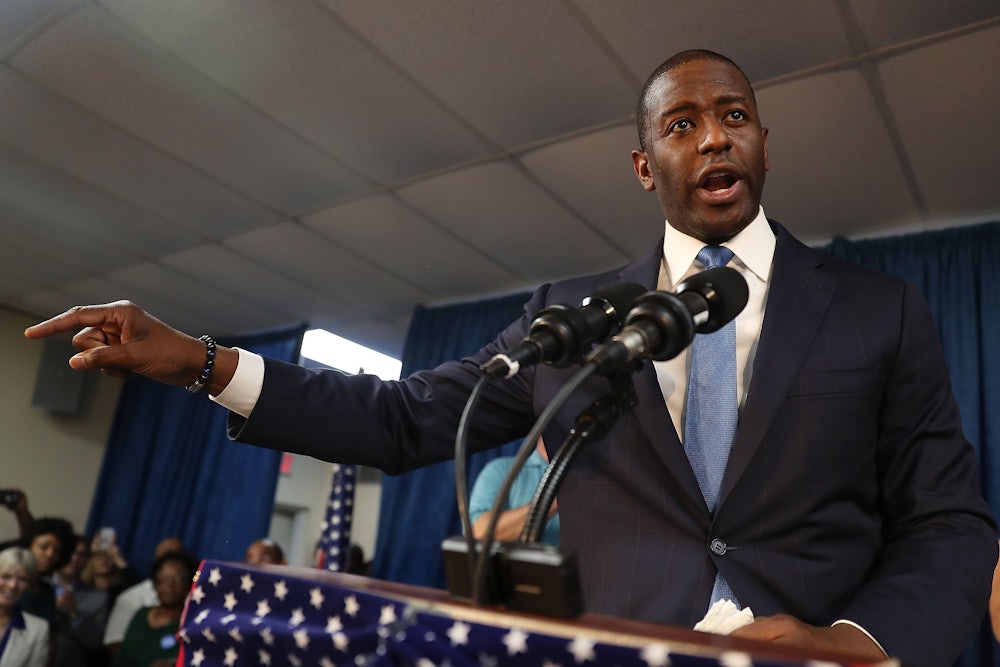

In 2014, years before he became the Democratic nominee for governor of Florida, Andrew Gillum was targeted by two gun-rights organizations, Florida Carry and the Second Amendment Foundation, which threatened to remove him from his post as Tallahassee city commissioner over a pair of local regulations prohibiting residents from shooting firearms in public parks. Despite the fact that these regulations, which were passed in 1957 and 1988, were no longer being enforced, the lobbyists argued that they violated a 2011 state law barring local governments from passing their own gun regulation ordinances. With the full weight of the National Rifle Association behind them, the gun groups sued the city of Tallahassee.

Facing personal fines of $5,000 and damages of up to $100,000 in addition to the threats to remove him from office—all for not officially removing the defunct laws from the books—Gillum defended his city in court. He did so without even the support of Tallahassee’s legal team, which was prevented by the same 2011 state law from supporting local legislators in such cases. In the midst of the lawsuit, he defined the stakes of the legal battle as a bid by red state governments to overturn the democratic will of blue cities: “It’s … about how these special interests and corporations, after getting their way with state government, are trying to intimidate and bully local communities by filing damaging lawsuits against officials like me.”

Gun control is just one of many areas where Gillum confronted intimidation tactics, first as city commissioner and then as mayor of Tallahassee. In Florida, cities are preempted by the state from raising their minimum wage, enacting paid sick days, restricting smoking in public areas, regulating the nutritional value of restaurant food, establishing public broadband networks, or regulating Uber and Airbnb. Ultimately, the court ruled in Tallahassee’s favor, but it left the firearms preemption law intact.

Tallahassee is hardly alone. Across the country, the past few years have witnessed a spike in state preemption of local authority—every state except one has at least one such law on the books and nearly three-quarters of states have three or more. In the past year alone, 19 new preemption laws were passed in different states. The effort has been quiet, but nonetheless coordinated and precise: In many states, particularly conservative ones, preemption law has rendered left-leaning local policy-making largely impotent. It has revealed yet another way Republicans have paralyzed government, while underscoring the need for progressives to win back not just Congress, but statehouses across the country.

For most of American history, preemption law was used differently. “Preemption was about aligning state and local law—making sure there were no inconsistencies,” says Kim Haddow, director of the Local Solutions Support Center, a national hub working to counter preemption. “It wasn’t used very often, and it was used by both Democrats and Republicans without much disparity.”

One of preemption law’s most significant functions was to establish statewide standards on civil rights. It’s only in the past decade or so that it has been widely used to establish a ceiling—rather than a floor—on benefits, quality of life, and equality. “The laws are punitive, they’re broad, and they’re a denial and distortion of democracy,” Haddow says. “It isn’t the voice of the people being truly represented by their elected representatives—it’s that voice being deliberately warped.”

Preemption laws are not inherently anti-democratic but become so when used to amplify existing racial and economic inequality. “What we’re seeing is conservative, mostly white legislatures really tying the hands of cities that are majority people of color,” says Jackie Cornejo, an organizer with the Partnership for Working Families. Cornejo’s colleague Miya Chen Saika explains, “The pro-preemption industry groups use the argument that we need to protect the uniformity of wages across the state. But the reality is that the only uniformity these corporate interests want to protect is the uniformity of African Americans earning the lowest wage in all sectors in all geographies.”

This aggressive manipulation of preemption law by corporate lobbyists has played a big role in transforming preemption from a largely neglected policy tool to a conservative blockade against progressive interests. The American Legislative Exchange Council—known as ALEC—has taken the lead, drafting model legislation to preempt everything from minimum wage regulations to sanctuary city policies. Representing over 200 corporate and nonprofit members and a quarter of all state lawmakers, the organization has immense influence over state law nationwide.

ALEC has been advancing corporate interests in statehouses since the tobacco bills of the 1990s, but entrenched itself further after the Republican wave of the 2010s that decimated Democrats at the local level. There are currently 25 states where Republicans wield absolute power—controlling the legislature and governor’s mansion—compared with only eight for Democrats. For progressive city officials attempting to compensate for gridlock in Congress or to counteract the White House’s deregulatory efforts, this alliance of state and corporate interests presents a formidable opponent.

Preemption laws have tended to sneak through state legislatures mostly unnoticed, with bills often passed in a matter of days. This quick turnaround has been a major obstacle in generating the public awareness necessary to build resistance. But there have been some successful efforts to thwart such laws. In Birmingham, Alabama, a federal appeals court ruled in July, after over a year and a half of pressure from local labor groups, that the state’s minimum wage preemption law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection rights. In California, organizers collected enough signatures to put a bill to repeal the state’s rent control preemption law on the November ballot.

The crucial next step, advocates believe, is to show these disparate movements that they are connected, and that the issue is larger than any one preemption bill. And they’re looking to a blue wave to make it happen—not in the House, but in state legislatures.

“Democrats for too long have been ignoring legislatures while Republicans have been, frankly, eating our lunches,” says Steve Farley, an Arizona state senator. “That’s why we’ve seen so much gerrymandering—Republicans have understood the power the legislatures have to be able to change a lot of things.”

Democrats are aiming to flip 14 legislative chambers in ten states in November, and advocacy groups are promoting a new generation of state leaders more favorable to local progressive power. Local Solutions Support Center, for example, aims to support progressive state legislators in challenging preemption law right away. “There is a reason Kris Kobach showed up on Trump’s doorstep on day one with a 365-day plan from the Heritage Foundation,” says Haddow, referring to the hard-line Republican secretary of state from Kansas. “Republicans are very good at thinking through ‘what do we want to move when we win?’ So, we’re taking a page out of their book.”

For his part, Gillum has a history of rallying leaders around the cause of local democracy, organizing a group of mayors into the first anti-preemption group in the country: the Campaign to Defend Local Solutions. Other candidates in this election cycle also have a history of anti-preemption work: Stacey Abrams, running for governor in Georgia, fought in 2017 against a bill that preempts local governments from requiring employers to compensate workers for last-minute scheduling changes.

Pushing back against preemption is becoming a theme for an emerging slate of local candidates. “There are a lot of young Democrats and progressives coming up and running for state legislatures who can have a big impact here,” says Mark Pertschuk, the director of Grassroots Change, an organization fighting preemption from a public health perspective. Pertschuk says preemption isn’t a cut-and-dry partisan issue. Democratic legislatures have also been guilty of overreach, such as this past summer when California’s overwhelmingly blue statehouse passed a bill preempting soda taxes in an effort to appease the American Beverage Association. The power of up-and-coming candidates to challenge preemption lies not just in their party ticket but in their good-government politics. “These candidates are much less likely to care what multinational corporations or trade associations want them to do than the old time political hacks,” says Pertschuk. “And they’re much less likely to listen to ALEC and others because of a campaign donation.”