In July, Jeff Merkley, the junior senator from Oregon, traveled to Iowa. The trip was his third in twelve months—a sign, political commentators said, that he was preparing to launch a presidential bid.

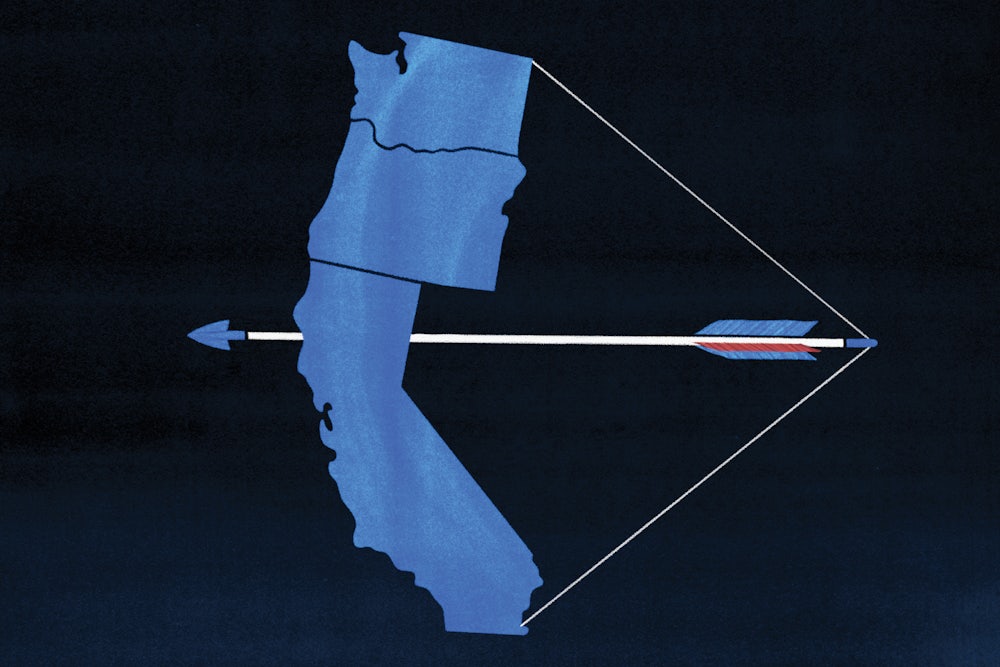

Nobody from the West Coast has ever won the Democratic presidential nomination. But two years from now, at least six will likely be competing for it: a mayor, a governor, at least two senators, even a few business executives. Tom Steyer, a venture capitalist from San Francisco, has already spent $40 million on a national ad campaign calling for President Trump’s impeachment and has held town halls in Iowa and New Hampshire. Jay Inslee, the governor of Washington, headed to Iowa in June, where he gave the keynote speech at a Democratic Party function outside Des Moines. Eric Garcetti, the photogenic mayor of Los Angeles, was there just two months before. On a swing through the Northeast in May, Garcetti also stopped by New Hampshire. (Senator Kamala Harris of California and Howard Schultz, the former CEO of Starbucks, are widely seen as presidential contenders as well, though so far they have refrained from visiting the early primary states.) The flurry of trips is instructive. With Donald Trump in the White House, a group of gifted politicians and public figures from the Pacific Coast believe that they are the best positioned to challenge him.

They may be right. A special brand of American liberalism, at once independent-minded and dedicated to the common good, has flourished in the West. And it could well be this tradition—with its commitment to immigrants, to equality, to free trade, and to environmentalism—that provides the best path forward for Democrats looking to unite their fractured base.

Americans tend to think of the West Coast as a liberal fortress. But not so long ago, Washington, Oregon, and California supported Republicans. (Much of the rural parts of all three states still does.) Westerners were attracted to the GOP’s valorization of individual independence, an attraction that sometimes manifested as libertarianism. They wanted to be allowed to do their own thing, without interference from the state. This emphasis on autonomy is still apparent. “We’re the people who believe in personal freedom,” Oregon Senator Ron Wyden told me.

Yet what personal freedom means to Westerners is now different from what it means to the GOP. As Republicans started to take more regressive stances on social issues, the desire for independence led voters in Washington, Oregon, and California in another direction, toward advocating for abortion rights, gay rights, and the legalization of marijuana.

With help from the technology industry, all three states also came to support loosening immigration restrictions. Tech startups lobbied for more H-1B visas, and not only because they needed skilled workers from overseas; immigrants or their children have founded 60 percent of tech startups.

Washington, Oregon, and California became strong proponents of free trade, as well. Tech companies, which rely on global supply chains, had strong incentives to block tariffs. So did Hollywood, which in the 1980s started to depend heavily on the international market. Nike, and the sports shoe and apparel companies that grew up around it in the Portland area, make many of their goods in Asia. Boeing, historically the linchpin of the Seattle economy, depends on international sales.

Starting in 1949, with California’s landmark Dickey Water Pollution Act, the West Coast also made itself the role model for environmentalism. More than half a million Californians work in renewable energy, ten times the number of coal miners in the entire nation.

In spite of the West Coast’s early conservatism, or perhaps precisely because of it, Democrats from the region are now uniquely suited to challenge Trump. All told, they have created a platform that is almost the polar opposite of his xenophobia, bigotry, protectionism, and environmental carelessness.

This isn’t to say that these Democrats won’t have obstacles to overcome in 2020; there are plenty. Even though all three states boast some of the highest state minimum wages in the country, housing costs and income inequality are major regional challenges. (California has a higher rate of inequality than Mexico.) Any presidential candidate from these states will have to answer for the problems back home. But of all the critiques leveled at these politicians, their alliance with the tech industry may be the most difficult to overcome.

Several prominent liberals in the Pacific Northwest, like Washington’s Suzan DelBene and Maria Cantwell, worked in tech before they entered politics, and even the politicians who didn’t work in tech rely on its donations: Kamala Harris’s donors are a “who’s who of major Silicon Valley players,” according to The Hill. At a time when some Democrats want the party to take a far tougher stance on monopolistic business practices, these connections could be a liability.

Then again, voters may not be concerned. Even after the Cambridge Analytica scandal of this past spring, the social media giants remain wildly popular. In June, a Pew Research Center poll showed that 74 percent of Americans think major technology companies have had a positive impact on their lives. Middle American cities such as Nashville, Dallas, and Indianapolis are eagerly seeking Amazon’s planned second headquarters, as smaller cities vie for Facebook and Google data centers. “Silicon Valley should be a huge ally to the progressive movement,” said Ro Khanna, a Democratic congressman from California’s 17th district, home of the technology industry.

Perhaps the most powerful reason Democrats from the West Coast have a real shot at the White House is that on many fronts they have been leading the resistance to Trump. Kate Brown, the governor of Oregon, refused Trump’s request to send National Guard troops to the Mexican border. Xavier Becerra, the attorney general of California, has buried the administration in lawsuits, at least 40, on topics as diverse as clean air and 3-D printed firearms. As Trump prepared to gut the Paris climate agreement, the three states made a deal with British Columbia to reduce their own emissions.

The region is likely to be significant for Democrats well before 2020. Of the 23 seats they need in order to take control of the House in November, Democrats hope to pick up eight in California, and as many as three in Washington. And now that its primary falls earlier in the presidential cycle, soon, not only will Californians need to visit Des Moines; Democrats from the Midwest and the East will have to make pilgrimages to California. As a result, state Senator Ricardo Lara has said, they will no longer be able to treat as “afterthoughts” issues that are for the West—and ought to be for the nation—of utmost importance.