Chris King wasn’t the person most Florida liberals expected Andrew Gillum to name as his running mate in the state’s gubernatorial race. A white, evangelical Christian who made a fortune buying up dilapidated Florida apartment complexes after the 2008 crash and refurbishing them as affordable housing, the Winter Park businessman had run against Gillum in the Democratic gubernatorial primary earlier this summer—and lost spectacularly, finishing fifth in the primary, with less than 3 percent of the vote.

His religion might have had something to do with his loss. King has called himself “the case study of whether faith is a deal killer in the modern Democratic Party.” But Florida, like many states, has a highly secular Democratic base that dominates the primaries. With the evangelical community nationally so firmly aligned behind the conservative right, the mere fact that King, who had never run for office before, was an evangelical, and a proud one at that, may have hindered his chances.

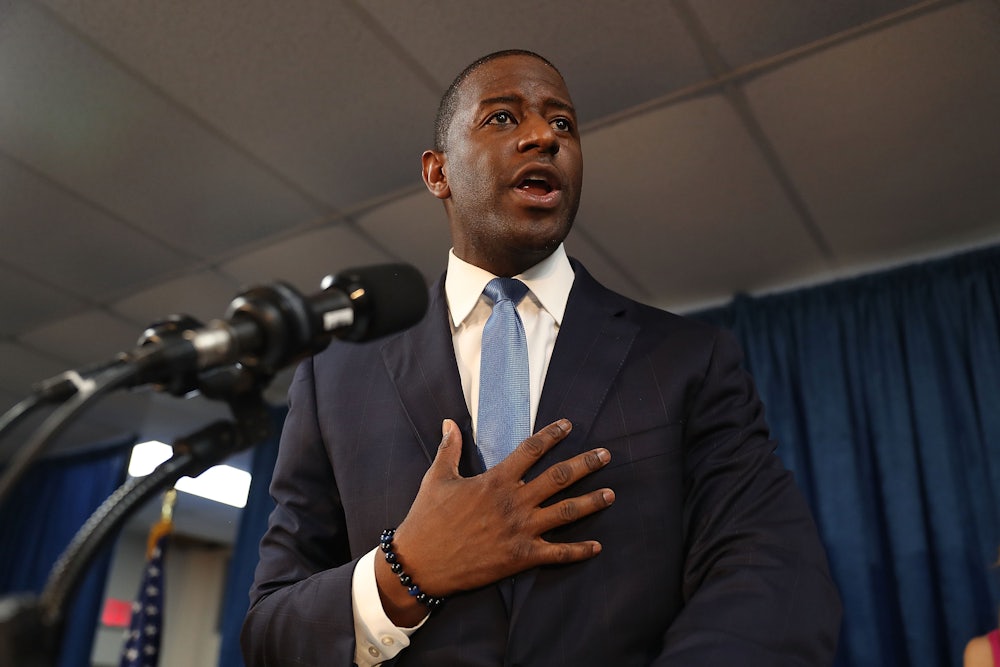

Evangelicalism might have held King back in the Democratic primary, but in a statewide general election, his ties to the Christian community could be an asset, and Gillum’s decisions of late suggest he understands that. Gillum himself is Baptist, and in August he spoke to supporters outside the Bethel Church in Richmond Heights, the South Dade neighborhood where he grew up. Apart from than his numerous visits to African American churches and appearances with black preachers, Gillum did not explicitly raise religion, nor, for the most part, did his opponents or interviewers. Still, his choice for lieutenant governor suggests that he will lean into it in his quest to win the governorship.

Since Gillum named him his running mate, King has insisted that “this is not a political marriage—this is not a marriage of convenience.” Regardless, it makes strategic sense. Barack Obama carried Florida with help from the young white evangelicals in the state. They may not be the voters who decide the primaries, but they are an important and often overlooked demographic in general elections within Florida and throughout the South. With King on the ticket, Gillum can craft a campaign message that mixes evangelicalism and left policies—a powerful combination that could provide a path forward for Democrats looking to win back seats in the Sun Belt.

This won’t be an easy sell. “Eighty percent of white evangelicals would vote against Jesus Christ himself if he ran as a Democrat,” Amy Sullivan wrote in the New York Times in March. Even though the president was married three times, divorced twice, and has a string of lawsuits and debts to his name, the white evangelical community continued to support him. Nationally, he got 81 percent of their votes in 2016. In Florida, he earned 86 percent. And despite being a lifelong Methodist and churchgoer herself, Clinton only got 19 percent. Still, that’s enough to open up an opportunity for Democrats in the South.

The rough political calculus in Sun Belt swing states like Florida and North Carolina is this: A coalition of African Americans, Hispanics (except older Cubans in Miami), single women, Jews and other liberal whites, millennials who vote, the LGBT community, and union members (except police and firefighters) usually brings the Democratic vote total to about 48 percent. In some election cycles, a strong enough candidate or a galvanizing issue can be sufficient to attract a smattering of suburban centrist swing voters who can help carry the state or district. Evangelicals are another crucial demographic. If Democratic candidates can pull in more than 19 percent of white evangelicals, say 25 or 30 percent, they can win.

In Florida, the complicated racial dynamics of the state make independents and white evangelicals doubly important. Latinos are split between the Democrats and the GOP. African Americans almost universally vote Democratic in Florida, as elsewhere in the Sun Belt. For them, the main issue is turnout. Thus the effective battleground is for a sliver of white voters: independents and winnable evangelicals. In fact, in 2008, an increased minority of white evangelicals was thought to have helped provide the margin of victory for Obama in both North Carolina and Florida.

Democrats have struggled to replicate his success in recent years, but according to Aubrey Jewett, a political scientist at the University of Central Florida, the reasons are more cultural than political. “These Christians tend to be more progressive in their political views,” Jewett told me, “but sometimes feel like the Democratic Party at best grudgingly accepts their support and at worst is outright hostile to their religious values.” That’s where a candidate like Chris King comes in.

Tall and handsome, with an incandescent smile and a Norman Rockwell family, the 39-year-old King has undeniable charisma. A graduate of Harvard and the University of Florida Law School, he’s a liberal who ticks all the right boxes, beginning with “common sense” gun control: banning assault weapons, high capacity magazines, and bump stocks; instituting enhanced screening, including at gun shows; and repealing Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law.

King also wants to raise the state’s minimum wage; legalize medical marijuana; welcome Syrian and other refugees; accept federal Obamacare Medicaid subsidies for the working poor; and restore voting rights to nonviolent felons. He opposes the state’s voter ID law, which he says are “part of institutional racism in Florida,” as well as private prisons, fracking, and offshore drilling. He was also the only gubernatorial candidate in Florida to categorically oppose the death penalty and prompted most of the others to refuse donations from the sugar industry. And, unlike most evangelicals, King unequivocally supports abortion rights and fully funding Planned Parenthood.

At the same time, King is also a lifelong, evangelical Christian: In high school, he belonged to the Fellowship of Christian Athletes; at Harvard, he was affiliated with Campus Crusade for Christ. Now, he is an elder at the nondenominational, evangelical church where the family worships in Orlando. His mother-in-law is a religious broadcaster with Good Life Broadcasting’s WTGL-TV Channel 45 in Lake Mary.

King didn’t campaign as a Christian candidate. However, the question often came up, and when it did, he was quick to connect it to the policies he advocated on the stump. “My faith always propelled me to serve others and to care about the needs of folks who’ve not had a voice and who need an advocate,” he told the Daytona Beach News-Journal. “So my politics are really a reflection of that. For the last 30 years, I would say that the Christian faith has in many ways been hijacked by a very conservative Republican ideology that is not reflective of a commitment to serve, and care for, and lift up people of all backgrounds. My politics I think reflect a much more comprehensive view of the Gospel of Love.”

Most Democrats today tend to run largely secular campaigns, but not so long ago, many used overtly religious language. For much of the twentieth century, various Christian reform movements were associated with the Democratic Party, from William Jennings Bryan to Jimmy Carter, the first declared evangelical. Child labor, women’s suffrage, unions, civil rights, and the fight to end the Vietnam War were all fueled by the religious left.

Returning to such language could be particularly useful at this political moment. Gillum and King are running against Ron DeSantis, a Republican congressman who has overtly aligned himself with Donald Trump on everything from immigration to trade to law and order. As Gillum and King look to draw out contrasts with their opponent, religion could help them campaign for a more compassionate government that helps the poor, the disenfranchised, immigrants, people with disabilities, and the unemployed. “King’s unusual combination of religion and progressivism could make him more palatable to some voters,” said Donald Davison, a political scientist at Rollins College in Winter Park.

Of course, King won’t ever be able to win over all the evangelicals in the state. Even for young, progressive churchgoers, his support of abortion rights “still may be a deal breaker,” Jewett noted. But it does provide a test case for what candidates on the left can do when they weave religion into their rhetoric—and perhaps even a path forward for 2020.

Barack Obama became president in 2008 with the help from white evangelicals, and there is no reason why Florida Democrats cannot use their shared concerns about social and economic justice and compassion for the disenfranchised to reach out to this winnable demographic.

After all, as Myriam Renaud, a religious scholar at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, has written, “If progressives hope to recapture the White House, they will have to persuade most, or all, of the white evangelical Christians who switched from Obama to Trump to switch back to their next candidate.”