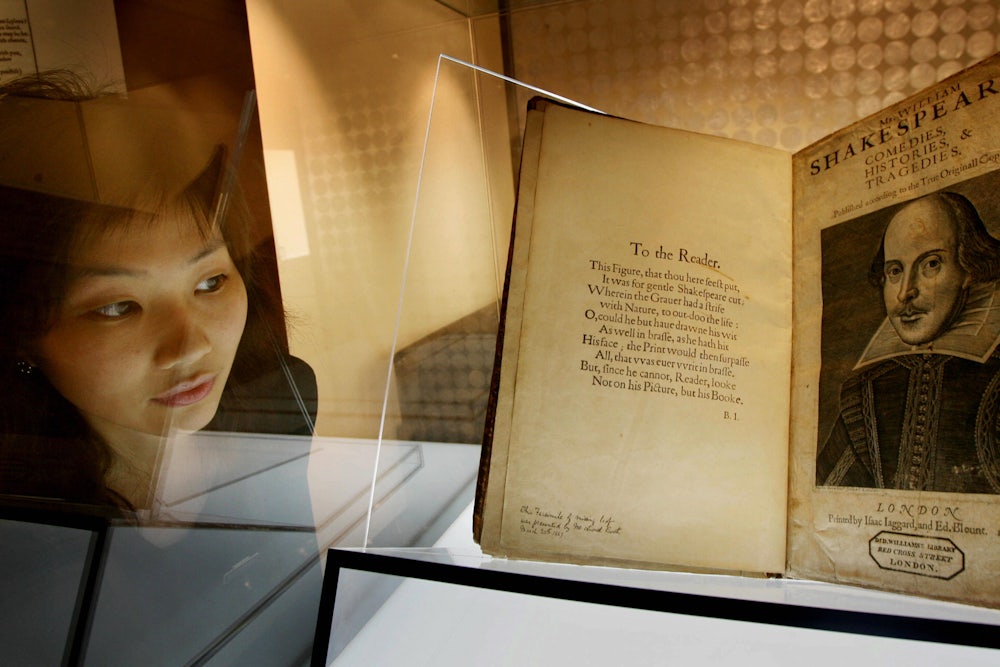

In 2011, Kevin Spacey played Richard III at the Old Vic in London. Director Sam Mendes put his actors in contemporary dress. Spacey wore fringed epaulettes in the style of Muammar Gaddafi, playing Richard as a modern dictator and arch manipulator who was ultimately left alone with his self-pity. It was terrifying. That production felt like the spiritual cousin of Nicholas Hytner’s 2003 production of Henry V at the National, also in London. His actors wore fatigues and transformed the Hundred Years’ War into the invasion of Iraq.

Both productions drew a big, bold arrow between global politics of our time and the events depicted in Shakespeare’s plays. But the nature of that arrow is more complicated than it might first appear. Were Mendes and Hytner using our own world as a key to unlock the unfamiliar speech of Shakespearean English? Or were they doing the reverse, cracking open current events (Tony Blair’s dissimulation, the media’s complicity with the “weapons of mass destruction” lie, Gaddafi’s rise) with the timeless lessons of a long dead dramatist?

The intention was probably something of both. Mendes and Hytner bet on the plays’ drama flowing in two directions, from the past into the present and vice versa. But the past of Shakespeare’s plays is not a fixed era. In none of his works did Shakespeare set the action in his own time, in England. Instead, he looked to the classical period, to medieval Britain, to unnamed islands full of magic. When Hytner and Mendes linked 2011 or 2003 to the worlds of Richard III or Henry V, they were skipping the possibility of connecting the present to a third era: Shakespeare’s own.

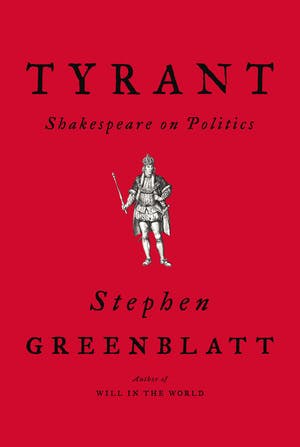

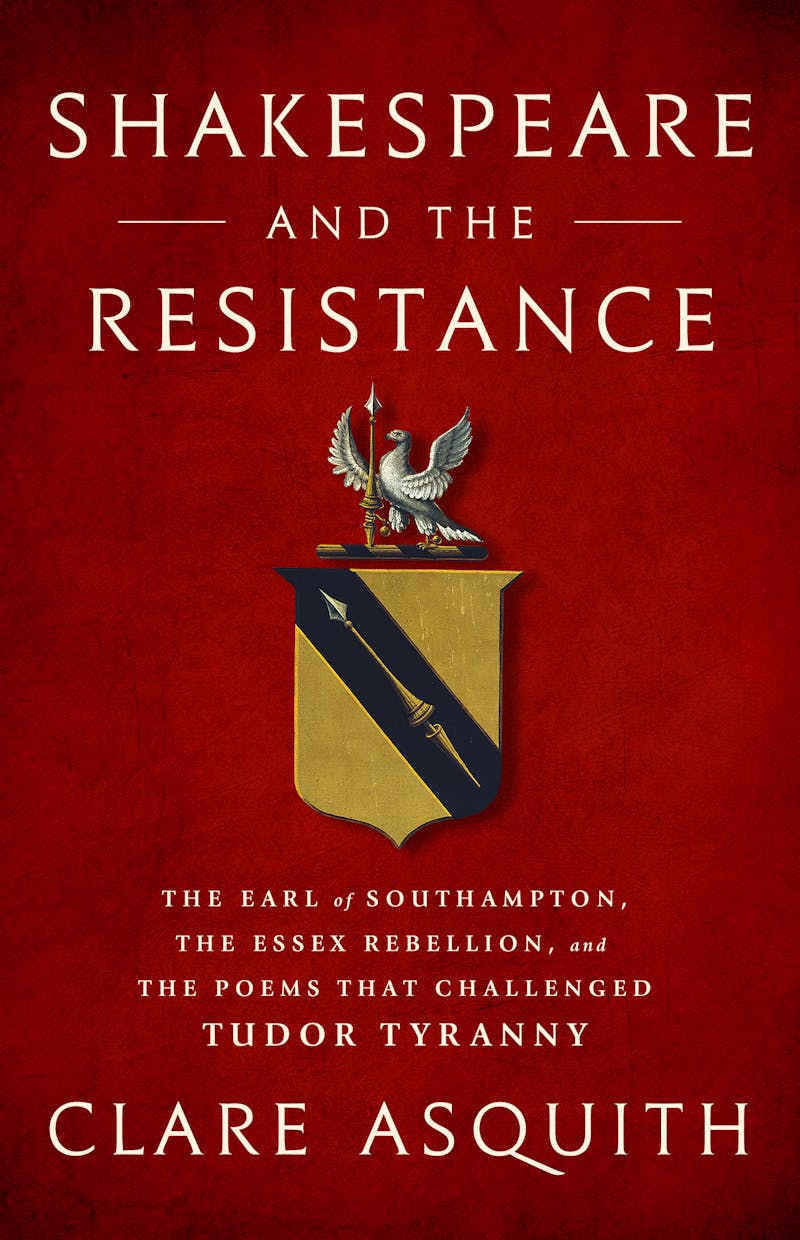

Two new books argue that Shakespeare wove oblique political critiques of the English establishment into his works, and that we can learn a thing or two from them in our own troubled times. Stephen Greenblatt’s Tyrant is a survey of all Shakespeare’s major despots: Richard II, Macbeth, King Lear, Coriolanus, Leontes of The Winter’s Tale, Saturninus of Titus Andronicus. It is a handbook that strongly implies but never outright states that it is a guide for living through the Donald Trump era. By contrast, Clare Asquith’s Shakespeare and the Resistance has the hashtaggier title, but the bolder scholarly content. In her book, she makes the case for interpreting Shakespeare’s narrative poems The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis as allegories of post-Reformation political discontent in Elizabethan England.

Unlike Hytner or Mendes, neither author is writing with artistic aims in mind. Instead, each yokes its analysis of Shakespeare to the current political context, and each is clearly being marketed with the big sticker of Trump. But the utility of these two books to our contemporary political climate is, to put it mildly, unclear. If Shakespeare toed a delicate line around sedition in his writing, as both Greenblatt and Asquith assert, it implies that the politics of literature in his time mattered—that those in power cared what was said in stories and plays. Today, we’re not so sure.

In the acknowledgements section of Tyrant, a slim volume of under 200 pages, Greenblatt recounts a conversation over dinner during Trump’s presidential campaign. “What can I do?” he asks the company. His friend replies, “You can write something.” Thus Tyrant was born, an act of resistance disguised as literary analysis.

He does not, however, mention the president. And Greenblatt has to begin with two inconvenient facts: Elizabeth I was not, in fact, a tyrant, and Shakespeare only made one reference in his entire oeuvre to a contemporary figure. Instead of directly protesting Elizabeth, Greenblatt argues, Shakespeare reacted to the thicket of conspiracy and fear that surrounded Catholicism and its suppression in the post-Reformation era.

As Shakespeare loved to do, Greenblatt works through puns. He writes of Catholic plotters as terrorists. He directly compares Mary Queen of Scots to Osama Bin Laden. He describes Jack Cade, the real medieval rebel whom Shakespeare wrote into Henry VI, Part 2 as a lying demagogue who wants to “drain” the “swamp” of government.

Greenblatt’s book has two chief projects: showing that Shakespeare was consciously responding to historical events, and defining the “tyrant” as Shakespeare saw it through a very Trump-colored lens.

As Greenblatt recounts, Shakespeare’s countrymen feared a power vacuum, since Elizabeth refused to name a successor. Henry VIII’s split from Rome had engineered a many-layered crisis, destroying the treasures of the monasteries and dividing English Catholics from Protestants along violent lines. The Earl of Essex staged an unsuccessful rebellion against Elizabeth in 1601, assisted by Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southhampton, who is thought to be the “fair youth” whom Shakespeare himself celebrated in many sonnets.

Most of the book is given over, however, to readings of Shakespeare’s monstrous kings. Greenblatt analyzes Richard III as an incel who blames women for not wanting him. Macbeth, for Greenblatt, doesn’t even want to be king but has been manipulated by evil sidekicks. King Lear is senile. Coriolanus is a narcissistic aristocrat turned demagogue. Saturninus is a nasty spoiled rich kid. Leontes is a jealous paranoiac.

Without a mention of the American government, Greenblatt puts together a scathing portrait of Trump through the words of a different writer. And most of Greenblatt’s historical arguments read less like scholarship and more like excuses to cite great lines that fit our times. “Civil dissension is a viperous worm / that gnaws the bowels of the commonwealth,” he quotes from Henry VI, Part 1. With his last words, Lear says, “Never, never, never, never, never.” Never … Trump? In Coriolanus Greenblatt finds the leader cursing the population’s “multitudinous tongue.” He also finds a line from the “citizens” that could act as a balm for those #resisters who still believe in democracy’s power: “The people are the city.”

Greenblatt himself has a fairly big role in the introduction to Clare Asquith’s Shakespeare and the Resistance. She argues that The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis are both keys to understanding Shakespeare’s politics. But there are scholars who think that such speculation, a pillar of the New Historicism movement that Greenblatt championed (he even coined the term in the early 1980s), is wrongheaded. The New Historicists want to break down the idea of Shakespeare as some independent genius different from everybody around him, seeking to place him in his proper context. But this approach has hit stormy waters among a smaller sector of scholars who want to use it to prove things about Shakespeare himself, particularly that he was a Catholic.

Asquith published an article in the Times Literary Supplement in 2001 arguing that Shakespeare’s The Phoenix and the Turtle contains evidence of his religious feeling. She also published a book, Shadowplay, in 2005, which furthered her work on the “religious and political subtext underlying Shakespeare’s work.” It was “vehemently rejected by Shakespeare scholars, who portrayed it as merely another attempt to prove that he was a Catholic,” she writes in her newest book. Asquith was tarred as one of the many speculators who wanted to show that Shakespeare was “an Italian, a covert homosexual, a Jesuit, Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, the Earl of Oxford ... a loyalist, a dissident, a Tudor apologist, an atheist, a Catholic, a Protestant, a Puritan, an elitist, a populist, a proto-Marxist, and the love-child of Elizabeth I.”

So, Asquith comes to this new book with a lot of personal baggage. But she plows ahead, tackling not our own political moment, as Greenblatt does in code, but specifically the Essex Rebellion of 1601. Asquith’s reading of The Rape of Lucrece essentially proposes the poem as a political allegory, with Lucrece the raped but stoical suicide as a figure for an England ravaged by the Reformation. Tarquin’s attack on Lucrece is a perfect “parallel to the royal takeover of the English church,” she writes, while Cardinal Wolsey’s liquidization of monasteries for cash represents an ideal example of revenue generated “ex rapinis,” by seizure. The poem represents a kind of political catharsis, Asquith argues, an “exhilarating” experience for Elizabethan readers “as they saw their own situation portrayed on stage, and, often, not merely portrayed but closely analysed and resolved.”

Her argument is bolstered by the dedication of The Rape of Lucrece and also Venus and Adonis to the Earl of Southampton, a patron figure to Shakespeare and supporter of the Essex Rebellion. In these poems she finds a portrait of Southampton that doesn’t tally with the traditional stereotype of the patron as an effeminate, ineffectual youth engaged in a love affair with Shakespeare. Instead, she finds in Shakespeare’s narrative poems an allegory of the “opponents of the late Elizabethan regime.” They are the enemies of tyranny itself, Southampton included. And Shakespeare, as their champion, is the voice of the resistance.

Both the narrative poems are deeply unpopular today, but were huge hits in their time. The reason for that, argues Asquith, was that they conjured a “dark world” of an England heading towards crisis. When we see “late Tudor and early Stuart England as a police state,” she writes, we can understand “the sudden explosion of sectarian hatred that fueled the Civil War.”

Asquith and Greenblatt’s books are very different projects. One seeks to dig into Shakespeare’s oeuvre to find clues about his own politics. The other, in the purported style of Shakespeare, writes blistering critiques of authority figures, but in a code that pretends to be about something else. They are both, however, books whose raison d’être is the Coriolanus-like tyranny we live under now.

On the face of it, Shakespeare and the Resistance is a book about history, not the present. But it also paints Shakespeare as a man “at the heart of the resistence movement,” as the publisher’s site puts it. If Asquith is arguing that a writer is always responding to his or her historical milieu, then the implication follows that she is doing exactly that, too.

The relation between Donald Trump and history is fraught with confusion and paradox. Alt-right Trump supporters are in love with an inauthentic vision of the European Middle Ages. His ethno-nationalist project itself is based in a pseudo-historical concept of America as the rightful property of its white heirs, a territory to be protected from Mexican invaders. Trump wants to make America great again, implying some ill-defined moment in the past that he, in the future, will recreate. It’s a view of history structured by certain nationalist ideologies that echo the historical visions of Nazism, for example. Still—it’s all chaos.

Where does this leave the historians? On the one hand, a scholar who cares about the sixteenth century, say, has to defend her own field’s validity in these anti-intellectual times. On the other hand, the rhetoric of #Resistance requires that she situate that validity in terms of its usefulness in the anti-Trump agenda. The R-word in the title of Asquith’s book invokes the slightly corny chorus of pussy hat–wearing bombast on Twitter. And at the end of all that work, a historian can’t help but turn to her books with the sinking feeling that none of this, in political terms, is going to make the slightest dent.

Shakespeare’s works are art, and there is a political value to his language that needs no set of historical references to be important. When we reduce literature down to its utility in a political contest, then we reduce its complexity and, in turn, its intrinsic worth. But in their insistence on the written word’s ability to act as a counterweight to power, it’s hard to see these books as anything but miniature acts of heroism. Tyrant and Shakespeare and the Resistance are trying, at least. Perhaps there’s life in the hashtag-resistance yet.