You would think there would be more literature about why men are so angry—the president, the mob in Charlottesville a year ago, the alt-right generally, the bar brawlers, the wife-beaters, the gay-bashers, the man who got more famous than he anticipated for screaming at a couple of women who were speaking Spanish in a Manhattan restaurant earlier this year. Add to this all the high-powered, high-profile men—the #MeToo perpetrators—who have been cruel and degrading to women, and the men who went berserk in early August when The New York Times appointed Sarah Jeong to its editorial board, slinging sexualized and racist insults at her because she had dared to criticize them. Anger is often entangled with entitlement—the assumption, which underlies a lot of the violence in the United States, that one’s will should prevail and one’s rights outweigh those of others.

Male anger is a public safety issue, as well as a force in the ugliest politics and social movements of our time, from the epidemic of domestic violence to mass shootings, and from neo-Nazis to incels. Because we normalize the behavior of men—and of white men in particular—the fact that a lot of far-right movements, such as the American neo-Nazi terror group Atomwaffen Division, are mostly male, is seldom noted. (Michael Kimmel’s recent book, Healing From Hate, which examines male fury in global politics, is among the valuable exceptions.) We have until very recently treated it as inevitable that women should adapt to these outbursts with Mace in our purses, self-defense lessons, and limits on our freedom of movement, tiptoeing around men who use their volatility to intimidate and control others.

Instead of a theory of male anger, we have a growing literature in essays and now books about female anger, a phenomenon in transition. Rebecca Traister’s new book, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, scrutinizes its causes, its repression, and its release in the last half-dozen years of feminist action, particularly in response to the treatment of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, and in the remarkable power shift that women demanded in #MeToo. Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger focuses on the ways in which women’s (and by contrast, men’s) emotions are managed, judged, and valued in contemporary North American life, while Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower is a first-person narrative about power, solidarity, race, gender, and their intersections.

These books arrive at a moment when a lot of women have changed and too many men have not—and some are, in fact, retreating into revved-up misogyny and rage against the erosion of their supremacy. Women no longer obliged to please men may finally be able to express rage, because we’re less economically dependent on men than ever before, and because feminism has been redefining what’s appropriate and acceptable. “Gender-role expectations . . . dictate the degree to which we can use anger effectively in personal contexts and to participate in civic and political life,” Chemaly notes. “A society that does not respect women’s anger is one that does not respect women—not as human beings, thinkers, knowers, active participants, or citizens.”

The same feminist transformations that have allowed this outpouring may eventually wear down some of the causes of our anger. Much of the anger discussed in all these books comes from being thwarted—from the inability to command respect, equality, control over one’s body and destiny, or from witnessing the oppression of other women. One of the pitfalls in trying to establish equality is to confuse gaining power with unleashing rage. For all of us this is the conundrum: How, without idealizing and entrenching anger, can we grant nonwhite people and nonmale people an equal right to feeling and expressing it?

There’s a zen story I heard long ago, about a samurai who demands that a sage explain heaven and hell to him. The sage replies by asking why he should explain anything to an idiot like the samurai. The latter becomes so enraged in response that he draws his sword and prepares to kill. The sage says as the blade approaches, “That’s hell.” The samurai pauses, and realization begins to flood in. The sage says, “That’s heaven.” It’s a story about anger as misery and ignorance, and awareness as the antithesis.

Verbal rage and physical violence are weaknesses. (Here I think of Jonathan Schell’s book on the power of nonviolence, The Unconquerable World, which makes the case that even state violence is ultimately weakness, since, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. … to speak of nonviolent power is actually redundant.”) Equanimity is one of the key Buddhist virtues, and anger is considered a poison in many Buddhist philosophies. It too often hardens into hate or boils up into violence. The sage makes clear that the samurai feels lousy when he’s about to commit a murder. Angry people are miserable. The sage also shows that the samurai is easily yanked around by what someone else does or says. Easily angered people are manipulable.

Yet here in the West, we talk about anger constantly, and we’re a lot more like the samurai than the sage. We assume, at least about male anger, that it’s an inevitable and normal reaction to unpleasant and insulting things, and that it’s powerful. This summer, NBC broadcast a video of a man from Nashville flying into a rage after he repeatedly propositioned a woman at a gas station and she turned him down. (Did he think women came to gas stations to get dates, not gas and maybe a soda? Or did he just think that women in general owed him, and he had the right to punish any stranger of that gender for disobedience?) In the footage, the man jumps onto the woman’s car, kicks in her windshield, and then assaults her directly. This inability to take no for an answer is far from rare. Since 2014, a Tumblr titled “When Women Refuse” has kept track of “violence inflicted on women who refuse sexual advances.” There is no shortage of examples, some of them fatal.

For those whose anger is sanctioned, its display can net rewards—if you want to be part of a system of intimidation and extortion, if you imagine the people you interact with as primarily competitors to be bullied rather than collaborators to be embraced. Some of the most privileged people on earth are raging and roaring their way through life—notably the president and his older white followers whose faces, scrunched in fury, can be seen at his rallies. These crowds are angry, perhaps because the alternative is to be thoughtful about the unfairness and complexity of this time and place and what they demand of us.

Much of what Traister and Chemaly address in their books is a double bind: We live in a world in which there is a good deal for women to object to, including the fact that a lot of men wish to harm and humiliate and subjugate us, but responding to that comes with its own penalties. When a woman shows anger, Chemaly observes, “she automatically violates gender norms. She is met with aversion, perceived as more hostile, irritable, less competent, and unlikable.” But even if, for example, she says quite calmly that gender violence is epidemic, she can still be attacked and characterized as angry, and that anger can be used as a way to discount the evidence, in a society that often still expects that women be pleasing and compliant.

A disturbing anecdote that Chemaly tells shows how early in life women are denied the right to be angry. At her daughter’s preschool, a boy keeps knocking down the towers that her daughter builds while his parents justify his aggression and refuse to prevent it. “They sympathized with my daughter’s frustration but only to the extent that they sincerely hoped she found a way to feel better,” Chemaly writes:

They didn’t seem to “see” that she was angry, nor did they understand that her anger was a demand on their son in direct relation to their own inaction. They were perfectly content to rely on her cooperation in his working through what he wanted to work through, yet they felt no obligation to ask him to do the same.

All three authors point out that race, as well as gender, sorts out whose anger is tolerated and whose is condemned. Among the black women Traister interviewed are Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and Representative Barbara Lee, who tells gripping stories about her own birth—in a hospital that nearly let her mother die because of her color—and about her mentor, congresswoman and 1972 presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm. Chemaly talks about the ways conservatives imagined and impugned Michelle Obama’s anger, and also reflects on her own family’s avoidance of women’s pain and anger. She wonders if it was rage that made her mother break all the best dishes by silently hurling them, if it was rage that her grandmother—kidnapped as a teenager by her grandfather—felt about a life in which she had little say.

Traister’s book documents moments when women have overturned expectations of silence and compliance in order to bring about change. As well as recent events, she presents vignettes from earlier eras of American history, covering Mother Jones, and the Industrial Workers of the World; Fannie Peck, who organized “Housewife Leagues” in Detroit; Rosa Parks and her only recently rediscovered, pre-bus-boycott feminism; the drag queens and transwomen who led the Stonewall Riot but were lost in the legend; and Anita Hill, who faced viciously condescending white men when she testified in Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearing. Traister portrays these women’s motives for standing up in each case as anger, an anger that gave them the energy to do what they did.

Yet sometimes it seems that energy might come from something else. Traister quotes Representative Lee saying that in public Chisholm would be “so cool, her voice and demeanor tough and strong and boom, boom, boom,” even when she was upset. “But get her behind closed doors? She’d let her guard down and acknowledge her pain.” Was her pain the same as anger? Or was it something else? Traister also quotes Garza saying that “what is underneath my anger is a deep sadness” and that it breaks her heart “to hear that a woman as visionary as Shirley Chisholm used to cry.” Later, Garza tells Traister that

the question for us is: Are we prepared to try and be the first movement in history that learns how to work through that anger? To not get rid of it, not suppress it, but learn how to get through it together for the sake of what is on the other side?”

What is on the other side is not quite clear, but Garza definitely takes the view of the sage, though she has compassion for the samurai in all of us. Perhaps Cooper is already there. Her book is as much a book about love as it is about anger: self-love and the struggle to find and hold it; love for the many women in her life, as well as public figures from Ida B. Wells to Audre Lorde to Terry McMillan to Hillary Clinton (they all talk about Clinton, of course); and at least implicitly a love of justice, of equality, of righting wrongs and telling truths. It is a warm and generous work, and a fierce one. All three books are compendiums of enormous numbers of anecdotes from and figures on recent American life, but Cooper’s is distinct both for its telling as the author’s own journey and for its—yes—eloquent personal voice, which, between her erudition (she is a professor at Rutgers) and her command of vernacular, is funny, wrenching, pithy, and pointed.

Returning to the fable, it seems the interaction between the two figures is about many less obvious things than fury and restraint. One of those things is power: If the sage had held the sword and the power of life and death with it, it’s easy to imagine his interlocutor would have been less eager to turn to violence, and their interaction would have stopped with the insult. Imagine a woman asked the sage the same question and he told her she was stupid and ineligible for enlightenment. Like the samurai, she might resent it, but, unlike him, she might not express that resentment, because expressing it will just open her up to other kinds of condemnation.

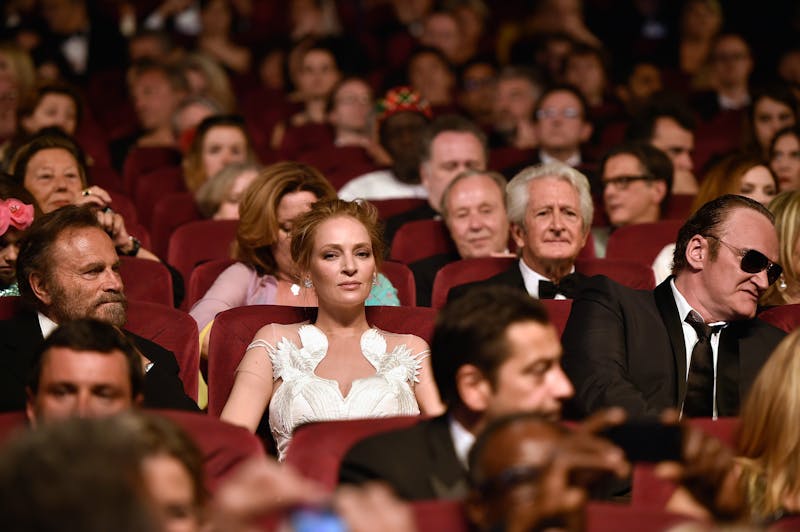

Or perhaps she accepts his definition of her worthlessness and his right to disparage her, so she’s not even angry, just miserable because she believes in her own inferiority. This is another kind of hell in which a lot of people reside. Don’t think of the warrioress Uma Thurman in the film Kill Bill, where she uses a samurai sword to slice off the top of an adversary’s head; think of the actual Uma Thurman, who seemed, before #MeToo, to have long normalized her abuse by director Quentin Tarantino.

Both Chemaly and Traister see Thurman as a counterexample to the more unrestrainedly angry women they describe. When Thurman was asked in October 2017 what she thought about Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo insurrection, she was reluctant to vent: “I don’t have a tidy sound bite for you,” she responded, “because I’ve learned—I am not a child—and I have learned that when I’ve spoken in anger, I usually regret the way I express myself. So I’ve been waiting to feel less angry. And when I’m ready, I’ll say what I have to say.” For Chemaly, this response shows that Thurman was fenced in by inhibitions; she should have spoken out in the moment. “The actress’s sense of her own position,” Chemaly argues, “reflected the precariousness of women, even powerful women, when they have this anger.”

Traister also analyzes that extraordinary footage of a clench-jawed Thurman (who is the daughter of a renowned Buddhist practitioner and scholar, and who perhaps has absorbed some non-Western ideas about the uses and abuses of anger). But she proposes that “sometimes, there is a strategy behind the suppression of rage; in Thurman’s case, she was waiting to tell her story in full.” Months later, in an interview with The New York Times, Thurman did just that, revealing that she considered that Tarantino had subjected her to “dehumanization to the point of death” when he forced her to perform a stunt in an unsafe car and she crashed, leaving her with permanent, painful injuries.

Thurman confided that up until that moment most of the abuse she had suffered from Tarantino—including spitting in her face—“was kind of like a horrible mud wrestle with a very angry brother.” The stunt setup was different, because it wasn’t just degrading but potentially fatal. “Personally, it has taken me 47 years to stop calling people who are mean to you ‘in love’ with you,” she reflected. “It took a long time because I think that as little girls we are conditioned to believe that cruelty and love somehow have a connection and that is like the sort of era that we need to evolve out of.” That is, women are conditioned to accept abuse and to accept it as its opposite (and to keep letting boys knock down their towers). The power to define your own experience is one of the powers that matters most.

Thurman impugned the reputation of two powerful men she’d worked with to speak of her own struggle and the plight of women exactly as she wanted to. She waited until she could be considered and effective. Her goal was not just what we call letting off steam—an Industrial Revolution-era metaphor that casts human beings as machines in which pressure builds up and must be released. Thurman’s goal was apparently to tell the truth in a way that had consequences, for the men who mistreated her and for the public at large—and perhaps for participants in the feminist insurrection underway, because stories like hers can fortify other women and the movement for women’s rights.

Anger itself is a catch-all term for a lot of overlapping but distinct phenomena. Among them are outrage, indignation, and distress, which are commonly born of empathy for the victims rather than animosity toward the victimizers. These feelings, which may last a lifetime, may not include the temporary physiological reaction that is bodily anger, with rising blood pressure and quickened pulse, tension, and often a surge of energy. That reaction is, in the moment, a preparation to respond to danger. It may be useful if you’re actually being attacked; when it becomes a chronic state, it turns the body against itself with impacts that can be devastating or even fatal.

I have often been struck by how some of the people who have the most grounds for anger seem to have abandoned it, perhaps because it could devour them. These are the falsely accused prisoners, farmworker organizers, indigenous rebels, black leaders, who are closer to the sage than to the samurai in our story, and powerful when it comes to getting things done and moving toward their goals.

I had a formative experience in the mid-1990s, when I was working with activists trying to expose the effects of depleted uranium on people who had been exposed to it in the 1991 Gulf War and at American weapons testing sites. I took two dedicated experts to a radio station, where they and the radio host talked at cross purposes throughout the interview. My colleagues were driven by love and compassion for the soldiers and the civilians in the United States and Iraq exposed to the stuff, and they wanted to talk about the suffering and the solutions. Their interlocutor—who if he were female might’ve been called histrionic, self-involved, and volatile—wasn’t really interested; he seemed to be motivated by hatred of the government and kept trying to turn the conversation to indictments of the institutions of power. He missed what his subjects were trying to say as he tried to beat their story into his mold.

Most great activists—from Ida B. Wells to Dolores Huerta to Harvey Milk to Bill McKibben—are motivated by love, first of all. If they are angry, they are angry at what harms the people and phenomena they love, but their urges are primarily protective, not vengeful. Love is essential; anger is perhaps optional.