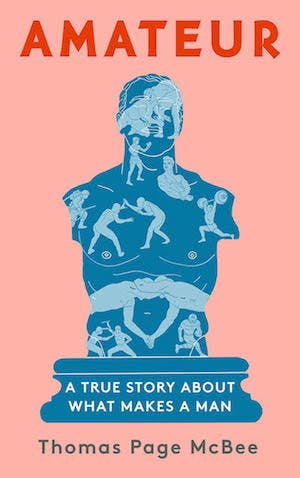

The beginning of Thomas Page McBee’s new memoir finds him locked in battle with another man. “I loved him even as I danced around him with my hands in the air,” he writes. Although this is the opening scene of Amateur, it’s also the story’s end, since the memoir is structured around McBee’s journey from regular journalist to journalist who boxes seriously on the side. It describes his training, his relationships with the men he meets at the gym, his changing interactions with his family and fiancée, before culminating in a big fight in Madison Square Garden. The book is about punching people but it’s more specifically about masculinity, and the complex architecture of rage, intimacy, and fulfillment that boxing represents. It is also a trans memoir, because McBee’s fight at Madison Square Garden in 2015 represented the first time that any trans man had done so.

Early in his transition, McBee experiences changes in his body and face, in the way that T-shirts fit him. His love for men’s bodies takes the form of a spectator becoming that which he desires: “I loved their lank and bulk and ease, their straight-razor barbershop shaves, their chest-first centers of balance.” But a change in the body is not a simple thing for the human mind to keep pace with. McBee finds himself coming up against internal impulses that are foreign to him, and social situations that provoke thoughts and actions with which he’s deeply uncomfortable.

One of those impulses comes when a man in New York City walks up to McBee, accuses him of photographing his car, and then calls him an asshole. McBee’s fists seem to curl themselves of their own accord, and he realizes how much he wants to break the teeth of this man who himself seems desperate to do the same. What can he do with this feeling? In the same sense, what can he do when his newly deep voice silences a room? When he speaks over his sister, without even realizing it?

McBee responds by confronting the problem of male aggression head on: He takes up boxing. During his training he discloses his transition to some, and not to others. In one case, a confidant does it for him, without his consent. Within that uneasy framework, McBee returns again and again to the idea of male violence, committing as much to that analytical journey as to the long runs and rope-jumping that his task demands.

In one such foray into analysis, McBee explains that sociologists use a classroom task called the “man box” to draw out young children’s developing ideas about masculinity. “Boys are asked what words or phrases go inside it, and what should be left out of it.” Their responses are commonly “a troubling primer in male socialization: Do not cry openly or express emotion. Do not express weakness or fear. Demonstrate power and control. Do not be ‘like a woman.’ Do not be ‘like a gay man.’”

With an associative flourish typical of McBee’s style, he explains that “sometimes the box is squared as an office or bounded more invisibly, the tight corners scripting the jocular camaraderie at the back of the bar.” Then again, “Sometimes it’s not a box, but a ring, iced or roped. And sometimes it’s the slow circles men make around each other in a street fight.”

The ring becomes a place for McBee to invert the “man box.” Where fighting conventionally symbolizes alienation, he finds intimacy. Where boxes ordinarily signify constraint, he finds freedom. And where aggression usually signifies hate, he finds love. In the final fight, McBee hits his opponent. But, he writes, “eventually I was not hitting him.” He hits his abusive stepfather, the doctors who treated his dying mother poorly. He hits everything inside him that already feels like it is getting slugged. Sometimes punching is not punching. And sometimes a box becomes an infinity.

The genre of the trans memoir is notable for the way that it offers cis readers an anthropological view of that which they take for granted. The author expresses a desire to be what the cis reader already is, trained up since infancy to perform their gender unconsciously. The trans memoir also functions chronologically, from point A to point B, charting the body’s progress towards a more normative gender presentation. Some books, like Akwaeke Emezi’s novel-memoir Freshwater, describe the author’s journey to a middle place, neither man nor woman. But the best-selling transition memoirs, like Juliet Jacques’s Trans or Deirdre McCloskey’s Crossing, almost take on the form of a success story, with the narrator achieving a complete transition.

Critically-lauded books about cis women are rather different. Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, for example, takes us nowhere except deeper into the emotional quagmire that her protagonist is thrashing in. Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, an older novel much feted in recent years, commits to an emotional present tense that totally forecloses the future. Both of those writers insist on the now, which is radical because women are traditionally depicted on a reproductive timeline, becoming a wife, then a mother, then a menopausal crone.

Because it works within its own rhetorical tradition, Amateur is marked by a heavy flavor of conclusion. It’s not that McBee delivers a highhanded lecture on the nature of contemporary masculinity—far from it. Instead, he writes with a tone that I suspect has been shaped by his career in journalism, which loves to match a high-flying concept with a lot of reportorial legwork.

Take one early idea that McBee picks up, the notion of a “crisis of masculinity” in turn-of-the-millennium America; that vague vision of lonely, older, white men who are tortured by their irrelevance. “Because of my conditioning, I suspected that the ‘crisis’ was far more complex than people understood,” McBee writes. He realizes that it has roots “far deeper than class and race and ‘tradition,’ that the bedrock of the crisis was inherent in masculinity itself, and therefore it encompassed all men, even the ones who felt they successfully defied outdated conventions.”

It’s a beautifully expressed observation. It leads directly to a second step in the argument: “It seemed to me that being in crisis was a natural reaction to being a man, any man, even if that wasn’t precisely what anyone else meant.” For McBee, masculinity holds at its center a set of paradoxes—tenderness through aggression; communication through silence—that can only be properly understood through crisis.

McBee structures his inquiry like a series of questions to be “reported out” into essays. (He initially attacked the challenge of boxing in an article for Quartz.) So even though this book relays a subtle, profound personal investigation into masculinity and personhood, the author emits the vibe of someone who takes very detailed notes.

If the trans memoir is going to keep pushing in this reportage-cum-personal journey direction, one danger is that transness will continue to be treated as an anthropological phenomenon, to be explained to cis readers, rather than a human perspective. McBee’s great twist is to treat masculinity itself as an anthropological phenomenon, represented by this bloody, extreme sport. Inside the fight, McBee finds reconciliation.