A big red kiosk greets you at the entrance of the new MoMA exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980. It’s a 1966 model of a modular design by Saša Janez Mächtig, made of reinforced polyfiber, steel, and glass. The kiosk is cuboid but with sinuous curves instead of vertices. As a video installed beside the kiosk explains, the design could be used singly, or combined with other kiosks. Across Yugoslavia, the kiosks were used as florists, newsagents, parking attendant lodges—anything. “How beautiful,” I said to my companion, an architect. She reached out as if to caress it. “How sad,” she responded, “that they did not realize how quickly rubber perishes.”

This is just one of the many wistful things that can be said about modernist architecture of the twentieth century. How sad it is that concrete, that most utopian and promising of materials, streaks so badly in the rain. How sad that this particular dream is dead. Such is the romance of these buildings for the contemporary Western viewer.

Brutalist architecture has become a kind of visual shorthand for Cold War-era socialism. Their looming concrete towers, so devoid of ornamentation, remind us of scary Soviet dictators. Their devotion to functionality also embodies socialist principles. Yugoslav architects built ergonomic housing, where each unit was the same size; large and accessible kindergartens, so that everybody of all genders could go to work; and dreamed of rebuilding entire cities for better, more efficient living.

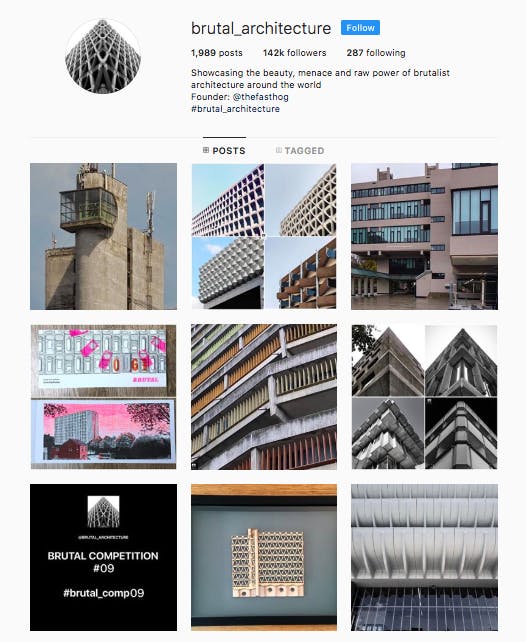

But this aspect of brutalism is not part of an ongoing political conversation. American culture is engaging with a postcard version of the design that found such favor with governments seeking to reimagine public space after World War II. This is the nostalgic, internet-optimized version of history, and it has become very popular. As The New York Times Style Magazine declared in 2016: “Brutalism Is Back.” Photographs of brutalist buildings are all over Tumblr (see: “Fuck Yeah Brutalism”) and Instagram, where accounts like @brutal_architecture showcase “the beauty, menace, and raw power of brutalist architecture around the world.”

Brutalist architecture has become the stuff of “aesthetic,” the shallow visual trickle that drips through social media and into the feeds of young people. It conflates brutalism with a fetishized minimalism—a Silicon Valley, cappucino minimalism that extends from apartment design to Everlane clothing to overpriced coworking space—at the expense of understanding what brutalism might actually contribute to the places where we live and work.

There are many utopias, perhaps as many as there are individuals to dream them up. The Yugoslav architecture of the new MoMA show historicizes one particular dream: of the Non-Aligned Movement, of big government budgets for a new region of the world, and of socialism writ large. The show’s insistence on that history gives the lie to the romanticization of brutalist architecture in the West.

Eastern Europe and Russia do not hold a monopoly on brutalism. The term itself comes from the French for “raw concrete,” béton brut, a term used by Le Corbusier. The kiosks are a great example of the quick, versatile, elegant functionality that all kinds of governments fostered in the post-war era. London is full of grand brutalist projects by Ernö Goldfinger; Le Corbusier’s own Unité d’habitation in Marseille is probably the first great achievement of the movement.

MoMA’s show deals with a period that begins with Yugoslavia’s break with Stalin in 1948, and ends with the death of the dictator Josip Broz Tito in 1980. In those years, Glenn D. Lowry writes in the catalog’s foreword, “the country, which offered a ‘Third Way’—an alternative to capitalist West and Communist East—enjoyed an outsize international presence for a time, thanks to its unique geopolitical situation at the intersection of East and West.” That presence was defined by Yugoslavia’s commitment to the Non-Aligned Movement, a global alliance of states with no declared affiliation to one of the world’s two major power blocs. As a leader in the movement, the Yugoslav state was under pressure to be exemplary in its services, urban planning, and architecture.

Between 1948 and 1980, as Martino Stierli and Vladimir Kulić explain in the introduction of the volume that accompanies the exhibit, “Yugoslav architects produced a massive body of work that can be broadly identified as modernist for its social, aesthetic, and technological aspirations.” You can see those aspirations in the large collection of kindergarten designs on exhibition, which freed parents of the yoke of childcare. “Belgrade apartment” was for a time a kind of international shorthand for a spacious, well-appointed flat in a tower block. These apartments were machines for living, in Le Corbusier’s phrase: domiciles in which socialist principles of equality, industriousness, and efficiency were built into daily life.

Yugoslavian utopianism ran from the ergonomics of office space to an entire region’s development. The first plan on the wall of the first exhibition room is not a building blueprint, but instead a 1968 “South Adriatic Regional Plan” by the urban planning institutes of Croatia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The smallest details of furniture design in this show are reflected in the project of the nation-state itself.

Of course, Yugoslavia is no more. So the grand projects of Janko Konstantinov, Kenzō Tange (a Japanese architect who did much in the Macedonian capital of Skopje), Vjenceslav Richter, or Slobodan Milećević is inevitably nostalgic. The whole state-sponsored architectural paradigm is, like Yugoslavia itself, kaput. But MoMA has done a very good job of keeping apocalypse out of these rooms. It concentrates on the functional aesthetics of a time and place, without reference to the violent end that would greet this state and ultimately affect the maintenance of the buildings honored. In so doing, it also avoids the question of why the principles of socialism may have been insufficient in keeping Yugoslavia together.

There is a cost to embedding a piece of art in its real-world context. Konstantinov’s telecommunications center in Skopje, for example, is a beautiful thing in and of itself. But only his drawings really exist outside history. The building itself gets used by people and rained upon by the sky, and relies on human beings to maintain it. It hardly seems fair to Konstantinov’s genius that his ideas had to become part of the physical world.

But architecture is for using, and brutalist architecture more than most. So, when its finest examples (in disrepair or in glorious form) are disconnected from their context, these concrete megaliths of the 1960s become something very strange indeed.

When Tumblr users reblog photographs of brutalist architecture, they turn them into pieces of furniture for their own pages. On Instagram, the effect of reblogging, or posting found images on a user’s feed, is to create of visual map to the user’s identity. There’s nothing wrong with this practice per se; it’s a very democratic way to access visual culture. But the social aspect to social media has turned the cultivation of aesthetics into an exercise in personal branding.

Every new generation does something new and destructive with its artistic inheritance. The great modernist architects did it themselves, cultivating an allergy to the curlicued fussiness of Art Deco, for example. But it is unlikely that the administrators of @brutal_architecture are much interested in the Croatian children who sat in those beautiful 1960s kindergarten classrooms—and those children are precisely the audience for whom these buildings were intended. It is not possible to relate to these buildings on a purely aesthetic level, because their use-function is an inextricable element of their form.

The historical and political relation of Brutalist architecture to our present moment is not the stuff of Instagram captions, not least because it won’t fit. It’s melted into the concrete itself. Towards a Concrete Utopia is an extraordinary show precisely because it engages with our romanticization of this form, but in so doing teaches, gently, about the time and the place.

For as long as we have Instagram accounts we’re going to keep emptying out the history from our visual signifiers, turning them into pretty shells that we arrange into advertisements for our own personal value. A utopia is whatever a person imagines it to be, after all. Utopia can be the size of the world, a nation state, a skyscraper, a kiosk; it can an iPhone screen or the dimensionless, disembodied gamut of the internet.

When a Tumblr or Instagram user pins a little bit of their identity on a beautiful old Yugoslav tower block, they are participating in a specific kind of capitalist utopianism, one that twists away from the politics of the original architecture. It’s the prerogative of each generation to destroy history in its own way. But some of those buildings, after all, are still standing.