This weekend, headlines across the internet announced that the British Museum was to “return looted antiquities to Iraq.” Eight tiny artifacts, some of them 5,000 years old, were handed to Iraqi officials in a ceremony on Friday, to be transported to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. But the antiquities were not, as the headlines implied, a part of the British Museum’s own collection; they were just identified there after police seized them from a dealer. The distinction is crucial, because the Museum houses one of the largest permanent collections of human culture on earth, some of which came from the old-school kind of “looting”—colonialism.

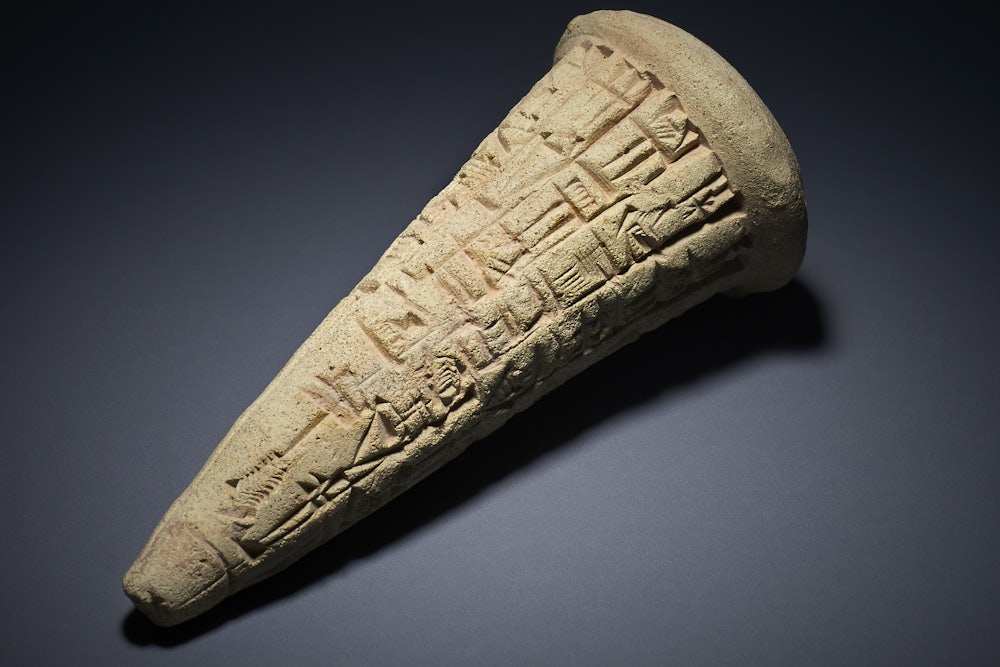

According to the Museum’s press release, the objects consist of an Achaemenid stamp seal; two stamp-seal amulets “in the form of a reclining sheep or showing a pair of quadrupeds facing in opposite directions”; and five Sumerian artifacts. Three of these objects are clay cones inscribed with the sentence, “For Ningirsu, Enlil’s mighty warrior, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made things function as they should (and) he built and restored for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” The inscription locates the objects as originally part of the Enninu temple of the Sumerian god Ningirsu.

The objects were seized by the London police in 2003 from a dealer who could not provide proof of ownership (and who is no longer in business). They were not among the treasures stolen from the National Museum of Iraq in 2003, but rather come from Tello in southern Iraq, where the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu once stood. The press release emphasized that the objects were identified “thanks to the British Museum’s Iraq Scheme,” which was founded in 2015 “in response to the appalling destruction by Daesh (also known as so-called Islamic State, ISIS or IS) of heritage sites in Iraq and Syria.” The program “builds capacity in the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage by training 50 of its staff in a wide variety of sophisticated techniques of retrieval and rescue archaeology.”

The scheme is no doubt an important one, and the region’s artifacts have been, no doubt, in danger. But as the media picked up the story of the handover, a strange impression arose: that the British Museum gave something back. The British Museum never gives anything back.

The story recalls last year’s flurry of articles promising the British Museum’s return of ancient sculptures to Nigeria and Benin. The Benin bronzes, as they’re known, were looted by the British in 1897 while they destroyed Benin City. The destruction was meted out as punishment for Oba Ovonramwen’s defiance, as he insisted on charging the colonizers custom duties. The Guardian and other outlets described excitement over a summit, planned for 2018, during which the British Museum might hand back the stolen treasures. British officials this year have so far only offered to loan the artifacts to Nigerian museums.

Many items in the Museum’s collection have similarly dodgy histories. In 2015, an exhibition called “Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilization” displayed items acquired after the British occupied Australia in the early eighteenth century and, over the course of the next 200 years, massacred thousands of its aboriginal inhabitants.

The most famous controversy over the Museum’s collection centers around the so-called “Elgin marbles,” named for Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, who obtained treasures of the Parthenon as a favor from the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and transported them to England. The longstanding argument for his actions, both then and now, is that the marbles were moved in order to preserve their integrity. Though this argument is not without its merits (and its holes), it’s not the overarching issue for British authorities. The real problem, I think, is the scale of restitution that could open up once a precedent is set. Responding to India’s call for the return of the Koh-i-noor diamond in 2013, for example, former Prime Minister David Cameron said, “I certainly don’t believe in ‘returnism,’ as it were. I don’t think that’s sensible.”

So, reading the news that the British Museum would “return” anything came as something of a surprise. The British Empire’s violent colonial actions are not regularly subject to re-examination. Tony Blair said in 1997 that the empire should be the subject of neither “apology nor hand-wringing.” In 2011, Cameron told his party that “Britannia didn’t rule the waves with armbands on” (armbands are British for floaties). It was 2013 before the U.K. acknowledged its torture and murder of the Mau Mau people in the 1950s, and agreed to pay compensation to survivors.

This week’s headlines invoked a fantasy version of the British Museum’s role in international relations. The director of the museum may have shaken hands with Iraq’s ambassador to the U.K., but he has not performed a genuine act of restitution. The British Museum has been styled in the press (and styled itself in its own press release) as a bulwark against looting. But the museum is a cathedral to the practice. The presence of the rest of the collection cast a long shadow over proceedings on Friday, and it showed the “return” for what it was: A simple case of stolen goods, intercepted.