In the middle of the 1970s, Zbigniew Brzezinski approached his friend, Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington, with a question: Is democracy in crisis? It was a subject of much concern at the Trilateral Commission, a kind of Rotary Club for members of the international power elite that Brzezinski had co-founded in 1973 with David Rockefeller, head of Chase Manhattan and grandson of the famous robber baron. With the Trilateral Commission’s backing, Huntington and two co-authors produced a survey of democracy’s health in the United States, Europe, and Asia. They found that faith in government had nosedived, political parties were fracturing, and efforts to pacify voters through more public spending had sent both inflation rates and deficits soaring. Too many people—Huntington’s list included “blacks, Indians, Chicanos, white ethnic groups, students, and women”—were demanding too much from politics, rendering the entire system ungovernable.

How needlessly gloomy all of this soon sounded. In 1992, Huntington’s former student Francis Fukuyama explained that the end of history had brought humanity to a “Promised Land of liberal democracy,” which offered an unbeatable combination of economic prosperity and political recognition. Capitalism and democracy fit together in a seamless whole, blocking out all other competing visions. Once intractable dilemmas of modern politics had been swept aside. The collapse of the Soviet Union had proved the bankruptcy of communism, and the taming of inflation had shown that democracies could manage their internal economic affairs. Even Huntington joined in the optimistic mood, writing a much-discussed work on a “third wave” of democratization that, beginning in the 1970s, had taken more than 60 countries from authoritarianism to democracy. The crisis was over, seemingly for good.

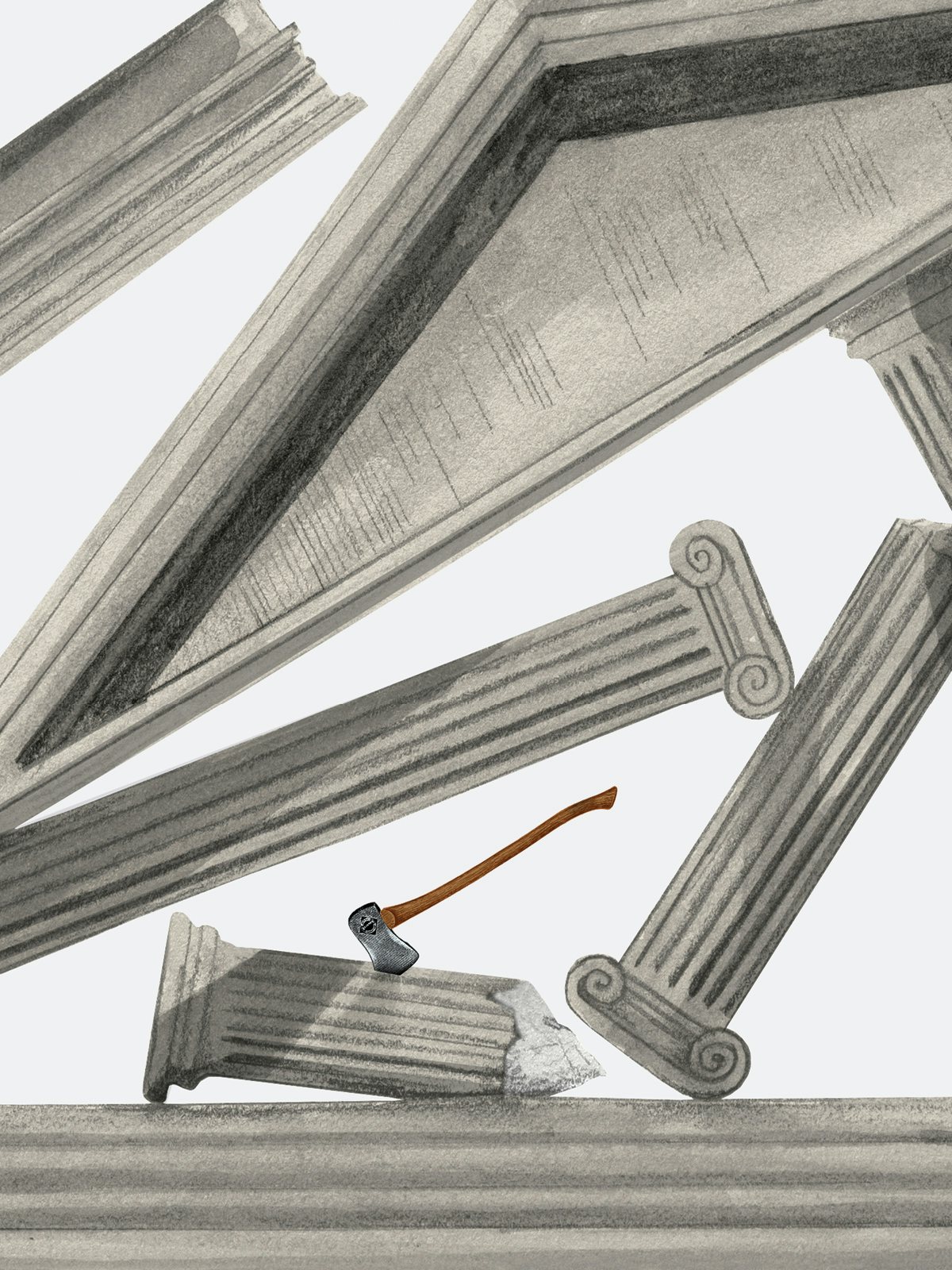

Today, of course, despair is back in style. The percentage of people who say that living in a democracy is “essential” has declined, and polls show rising support for nondemocratic forms of government, from technocracy to military rule. An international populist revolt has turned the previously unthinkable—from Britain exiting the European Union to Donald Trump entering the White House—into the new normal. This is a crisis that, provoked by the right, has so far been theorized by the center-left in gloomily titled books ranging from Madeleine Albright’s Fascism: A Warning to Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die, both New York Times best-sellers.

Now two more books have arrived with cases that hover between cautious optimism and measured despair: Cambridge political theorist David Runciman’s How Democracy Ends and conservative pundit Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West. Goldberg’s book has been taken up in the beleaguered ranks of the intellectual right as one of the best explanations the movement has for the rise of Trump. Runciman, on the other hand, is too idiosyncratic a thinker to belong to any tribe except the professoriate. Both authors came of age in the 1980s—Runciman was born in 1967, Goldberg in 1969—and made careers in the long 1990s, that period between the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the financial crisis of 2008. Dire warning about democratic crisis belonged to their childhood, and so did radical challenges to the political system. Intellectual maturity required putting away juvenile delusions—until, suddenly, maturity itself seemed like the delusion.

In their own ways, both push against the conventions of the emerging literature on democracy’s latest breakdown, which has tended to speak in earnest tones of endangered norms and existential threats to the republic. In other ways, they remain trapped in the mental world of the long ’90s, when pragmatists were supposed to limit themselves to tinkering with the status quo—a way of thinking that helped produce today’s populist revolts in the first place. Yes, democracy is again in crisis. But in every democratic crisis lies a political opportunity.

One of the many virtues of How Democracy Ends is Runciman’s insistence that talk of impending doom is almost certainly overblown. “The crisis is real,” he notes, “but it is also a bit of a joke.” Runciman is an inveterate contrarian who has no patience for the melodrama of the Resistance. Trump is not Hitler, and a fascist coup is not lurking around the corner. The true danger is much more banal. “Mature, western democracy is over the hill,” he writes. If this is a crisis, it’s a midlife crisis. Democracy’s best days are behind it. The great battles of the last century—expanding universal suffrage, extending civil rights, establishing the welfare state—have been won. Yet people are still unsatisfied, and Runciman sees no plausible way to restore their lost faith.

When a representative democracy thrives, it does so by offering enough benefits to citizens that they are willing to overlook the system’s inevitable frustrations. Following Fukuyama, Runciman emphasizes that the rewards are both material and intangible. Higher living standards and the recognition that comes from having your vote counted are an appealing combination. Fail to deliver on either front, however, and compromise starts to look like betrayal. Fail on both counts, and the prospect of abandoning democracy becomes increasingly attractive. This will be especially true in countries with shallow democratic traditions and lower living standards. The less a nation has to lose, the easier it is to make this switch.

The question is what system to switch to. Democracy’s advantage in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse was that it appeared to have proven itself the least bad of the available options. According to Runciman, this is no longer the case. What he calls “pragmatic twenty-first-century authoritarianism” has found a new way of satisfying demands for economic prosperity and political recognition. Compare authoritarian China with democratic India. Today, China’s per capita GDP is nearly five times higher than India’s, its poverty rate is half as large, and the average person’s lifespan is longer. As for political recognition, there’s the pride that comes from being part of a nation whose success is envied around the world. Whether the balance the Chinese government has struck is sustainable remains to be seen, but, for now, young democracies with low standards of living have an attractive alternative to consider.

For the mature and wealthy democracies of Western Europe and the United States, Runciman believes, the future holds the same fate that awaits most of us: death from old age. “Democracy could fail while remaining intact,” he writes. Even as governments deliver fewer gains, the political systems in such countries are too entrenched, populations too old, and economies too robust for the system to collapse outright. Instead, a long period of decline, during which institutions perform just well enough to avoid catastrophe, is the most likely outcome. Slowly, something new will emerge. It might still be called democracy, if the brand is worth preserving. In reality, it will bear as little resemblance to what we understand as democracy today as our system does to Athens in the time of Pericles.

The shape of this new order, Runciman argues, will be determined by future technological revolutions whose contents are today unknowable. “Mark Zuckerberg,” he writes, is “a bigger threat to American democracy than Donald Trump.” Politicians will continue to promise transformative change, but real authority will devolve to experts tasked with managing the technical problems facing a modern society, and individuals will find meaning in private communities isolated from the larger public. Imagining the system that gives full expression to these tendencies—he calls the first “solutionism” and the second “expressionism”—Runciman allows himself a rare moment of nostalgia for what will be lost. “The institutions we need to confront the political emptiness we increasingly feel,” he writes, are being hollowed out. The demos will be too splintered to exercise its will, and even if voters somehow united, they wouldn’t know what to do.

Beyond this, Runciman has few predictions to make. Pick a scholarly discipline, and he can give a good reason for questioning its value in navigating the present. The social sciences can tell us everything and more about the intricacies of our political system but precious little about how the enterprise as a whole hangs together. History is just as duplicitous a guide, filled with misleading parallels that lead us to assume we know more about how the future will play out than we do. Yet his own accounts of pragmatic authoritarianism and unchained technocracy have a distinctly early-twentieth-century flavor to them, back when political visionaries foresaw the dawning of a reign of engineers. As Runciman noted in his last book, The Confidence Trap, a more sanguine study of democracy published in 2013, this earlier bout of pessimism gave way to yet another period in which democracy’s triumph seemed unassailable, until the onset of the Cold War caused another crisis of faith. The case for optimism is easy to make in good times, and when conditions are dire, nihilism looks like prudence.

Even if his vision of the future comes to pass, there’s something unsatisfying about Runciman’s refusal to speculate on what might be done to avoid the dreary scenario he conjures. He could be right that in the long run democracy is doomed. But as his Cambridge predecessor John Maynard Keynes noted, in the long run we are all dead. It would help to have a little more guidance in the meantime.

Jonah Goldberg is not nearly so reluctant to weigh in. There is no purer representative of the modern conservative intellectual than Goldberg, senior editor at National Review; regular contributor to Fox News; and fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he holds a chair endowed by hedge fund billionaire Cliff Asness. Shaped by the intellectual movement that developed around William F. Buckley Jr. in the middle decades of the twentieth century, he is a believer in the efficiency of markets, the wisdom of tradition, and the dignity of bourgeois virtues.

Around National Review, this synthesis of moral conservatism and economic libertarianism was known as fusionism, and today Goldberg is its most forceful defender. From justifying the war in Iraq to championing the Tea Party, he has been a reliable voice from the right, usually with a nod to the conservative canon and a decades-old pop culture reference that allows him to gin up a few hundred words on the radicalism of Dead Poets Society or the insights of Groundhog Day.

Goldberg made his most significant contribution to the movement in 2008, with the publication of his first book, Liberal Fascism, which claimed that contemporary liberalism was, if not fascist, then at least fascism’s “well-intentioned niece.” “I have not written a book about how all liberals are Nazis,” he wrote, in a work whose cover featured a smiley face with a Hitler mustache. But he did write a book arguing that fascism and Progressivism were united by their rejection of laissez faire, making it possible for him to place Hillary Clinton in an intellectual tradition that reached back to Benito Mussolini. This thesis outraged liberals and historians—categories with significant overlap—but the book was a more interesting failure than its critics admitted, and Goldberg was right to draw attention to often neglected aspects of American history, including the importance of eugenics to Progressives and the scale of the domestic repression imposed by Woodrow Wilson’s administration during World War I.

The book was a hit, peaking at number one on the New York Times best-seller list and solidifying Goldberg’s position in the conservative media hierarchy. Then came Trump. Like many other conservatives, Goldberg supported much of Trump’s agenda, including a border wall, which he had been calling for since 2006. But he saw Trump himself as a walking insult to the American right. “Conservatives have spent more than 60 years arguing that ideas and character matter,” he wrote in the fall of 2015. “That is the conservative movement I joined and dedicated my professional life to,” and it had no place for figures like Trump.

In 2016, he learned that most conservatives had signed up for a different movement. Shortly after Ted Cruz dropped out of the primaries, Goldberg informed participants in a National Review cruise along the Danube that he still could not support the presumptive Republican nominee for president. “When I announced on the boat that I would never vote for Trump,” he recalled, “many in the audience gasped.” Trump noticed Goldberg’s criticism, writing in his campaign book, Crippled America, of the “truly odious” commentator being his “usual incompetent self.” Goldberg has kept up the fight since Trump has taken office, rarely objecting to the administration’s policies but always ready to spar with Sebastian Gorka on Twitter. That’s been enough to earn him the contempt of the president’s loyalists and a strange new respect from the liberal media.

Suicide of the West is Goldberg’s reckoning with the long road that has led to now. Whereas Liberal Fascism offered a mishmash of political and intellectual history, his latest book is more a work of pop-historical sociology, with doses of economics, anthropology, and psychology thrown in for good measure, all presided over by the spirit of Friedrich Hayek. Reflections on everything from the torture practices of the Assyrians to Japan’s most recent Godzilla movie sprawl across its 464 pages. Buried amid the plot summaries of Mr. Robot and block quotes of Woodrow Wilson is a simple argument: Liberal capitalism has brought unprecedented prosperity but is perennially in danger because it runs counter to an unchanging human nature.

At the core of Goldberg’s narrative is an event that he, borrowing from the philosopher and anthropologist Ernest Gellner (described here, weirdly, as a historian), called “the Miracle.” Once upon a time, the story goes, the overwhelming majority of humanity lived in grinding poverty. That time lasted from before recorded history up to the eighteenth century, when a small but increasing proportion of the population began to experience sustained economic growth. The result is that today billions of people live longer, healthier lives than would have been imaginable before the Miracle. Scholars disagree over the timing of this shift, but, give or take a century, Goldberg’s story checks out. We take economic growth for granted today and lament when it clocks in at a measly 1 percent, but even that is a profound departure from the historical norm.

According to Goldberg, there’s a good reason for the Miracle’s late arrival. Humans are tribal creatures by nature, built to live in small groups that fear the unknown. The emergence of modern economic growth required an intellectual revolution that ran counter to all of this. It put respect for free markets (capitalism) and individual rights (classical liberalism) at the center of society, challenging instincts hardwired into humanity’s collective unconscious by some 250,000 years of evolution. The human species is old, the Miracle is new, and the two have not yet come into alignment. This is where the “suicide” of the book’s title—borrowed from the conservative philosopher James Burnham’s 1964 work of the same name—enters the picture. Populism, nationalism, and identity politics are ways our tribal nature rebels against the liberal capitalist order. Turn away from the Miracle, Goldberg warns, and humanity will return to the squalor and misery that is our natural condition.

Nothing in this account of liberal capitalism requires the presence of democracy. In eighteenth-century England, which Goldberg treats as the site of the Miracle’s first appearance, fewer than one in five men had the right to vote. Not until 1918 did all adult British men win suffrage, and not until 1928 did women join them. Liberal capitalism might be desirable, but it is not necessarily democratic. Historically, the two were more likely to be seen as antagonists than allies. That’s certainly how Hayek understood them, and he put liberal capitalism first. So, in the past, has Goldberg. “I’m in the camp,” he wrote for National Review in 2006, “which holds that liberalism is more important than democracy.... I mean liberalism in the classical or philosophical sense: rule of law, individual liberty, free markets, free expression, etc., etc. Lost on many people is the fact that these things don’t necessarily come with democracy. Indeed, democracy can often take these things away.”

Goldberg places the blame for democracy’s most recent attempt to “take these things away” squarely on the left. Suicide of the West is preoccupied with the influence of what could be called Social Justice Inc. His taxonomy of this group includes not just the tenured radicals who so often feature in right-wing polemics, “but also diversity consultants, administrators, and various outside activist groups,” all of whom “have a vested interest in heightening racial and sexual grievances for the simple reason that they make a living from such things.” This is Goldberg the Nietzschean, who sees left-wing radicals concealing their will to power underneath bromides about making a better world. Barack Obama is his leading representative of this group. “He is part of an entire social and psychological movement that basically says the sort of white middle-class majority that ran this country for a very long time is the problem,” Goldberg told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt in the spring of 2016.

Which, according to Goldberg, brings us to Trump. “Trump is,” he explained to Hewitt, “a response to the sort of bile that I think Obama has injected into the American politics.” Trumpism, too, in Goldberg’s view, is not merely “an alternative to the worst facets of progressivism” but “a new right-wing version of them.” He attributes this mutation to the failure of the Tea Party. In his telling, the Tea Party began as an authentically conservative movement dedicated to limiting the size of government, paying down the deficit, and respecting the Constitution. (“I spoke to many of their rallies,” he notes.) Then the social justice warriors got to work. “What turned so many Tea Partiers into tribalists,” he argues, was the experience of being “demonized by the media and Hollywood as racist yokels and boobs.” Out of frustration, they succumbed to the eternal lure of the tribe and decided that the time had come to Make America Great Again. And so, thanks to both the provocations of the left and the clash between human nature and liberal capitalism, the right turned to Trump.

That’s one version of the story, and I’m sure it tracks with Goldberg’s personal experience. He was the one speaking at the rallies. But it doesn’t seem like he did a good job listening. After conducting interviews with Tea Party members, political scientists Vanessa Williamson, Theda Skocpol, and John Coggin concluded that, while Tea Party members did support deficit reduction and cuts to government spending, the movement was powered by the sense that an unaccountable political elite was showering undeserving freeloaders with money taken from the taxes of hard-working Americans. They loved big government when it benefited them, especially Social Security and Medicare. But the issue that provoked the strongest emotional reaction was immigration, which was just one part of a thorny tangle of questions related to race. Polls of Tea Party members revealed high levels of racial resentment: According to one survey, 59 percent weren’t confident that Barack Obama was born in the United States. “I just can’t relate to him,” one Tea Partier said of Obama. But they could relate to a billionaire reality star who said exactly what they wanted to hear.

These tendencies go back much further than the Tea Party, and so do the origins of Trumpism. Goldberg needs a sweeping theory of modernity to justify his claim that Donald Trump’s rise is a rupture in the conservative tradition. A simpler story would begin by acknowledging that mobilizing the resentments of white voters against both racial minorities and cultural elites has been an essential strategy for the modern right from the days of Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon up to the present. More recently, the right-wing infotainment machine—Fox News, talk radio, and the online opinion swamp—turned a political project into a profitable business. It also made minor celebrities out of figures like Goldberg, self-proclaimed guardians of true conservatism who fancied themselves warriors in a battle of ideas. Now it’s found suppliers who better understand their audience.

Like Runciman, Goldberg has emerged from his ruminations with a melancholy outlook on the future. “I haven’t felt this kind of alienation from politics in a very long time,” he wrote during the book tour for Suicide of the West. “It’s not disgust so much as a kind of exhaustion.” Exhaustion is a good term for the impression Runciman conveys, too, though in his case it’s the weariness of the perpetual cynic bemused at the naïveté of the innocents who buy into what he calls the “empty promises” of modern politics. It’s also a fair description of the entire crisis-of-democracy literature, in which the warnings about imminent disaster ring with clarity but the obligatory summons to a better tomorrow come out in a mumble.

Today’s populist fever could soon break. By 2021, Trump could be working in real estate full-time again, the blandest of Democrats could be in control of government, and pundits could be heralding the revenge of the norms. But it’s also possible that a more profound shift is underway. As the political theorist Corey Robin has observed, when an old order is collapsing—whether it’s New Deal liberalism in the 1970s or Reaganite conservatism and Clintonian neoliberalism today— it is easy to confuse the waning of a particular political system with a more fundamental breakdown of democracy. Just as Huntington’s world gave way to Fukuyama’s a generation ago, democracy’s latest crisis opens the way for a new kind of politics.

Lately, a single day’s news can offer glimpses of both the worst and best futures: The Supreme Court rules in favor of the White House’s travel ban in the morning, and at night Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez topples a pillar of the Democratic establishment. A revanchist conservatism fueled by white nationalism waits on one side, and a left committed to reviving socialism for the twenty-first century lies on the other. For now, the scales are weighted clearly in favor of the right. But as defenders of normalcy have learned in the last two years, nothing lasts forever.

American democracy might have entered its golden years, but new blood is rejuvenating it every day—including next January 3, when Ocasio-Cortez will become the youngest woman ever to serve in Congress. For all Goldberg’s emphasis on an unchanging human nature, he misses one of its most important features: To each new generation, yesterday’s hard-won victories are just another part of the world as they have always known it. That refusal to be dazzled by old achievements is what makes progress possible. And it just might save democracy. Today, the suicide Goldberg warns against is one potential outcome, even if a remote one; the senility Runciman predicts is an option, too, maybe a likely one. But a third prospect is coming into sight: rebirth.