Of all the human endeavors that lend themselves to cinematic depiction, the act of writing—as opposed, say, to painting or playing music—has always seemed to me the most difficult to portray. The problem remains: how to show on the screen something that is inherently interior and static, except for the sound of a pencil scratching on paper, or more likely, the click-clack of fingers on a keyboard? In a recent piece in the Times Literary Supplement, the British writer Howard Jacobson referred to “the nun-like stillness of the page” and quoted Proust’s remark that “books are the creation of solitude and the children of silence.” None of this bodes well for the clamorous imperatives of the screen, with its restless camera movements and need for compelling dialogue.

At best we might have a shot of the writer sitting in front of a manual typewriter, smoking intently and staring into the middle distance in between noisily plunking out a few sentences. Crumpled sheets of paper on the floor attest to the anguished perfection required to wrest the right word or phrase from the welter that beckons, but in the end the Sisyphean labor of writing—the means by which thoughts or imaginings are transferred from the mind to the page—is a mystery that no one image or series of images can hope to capture.

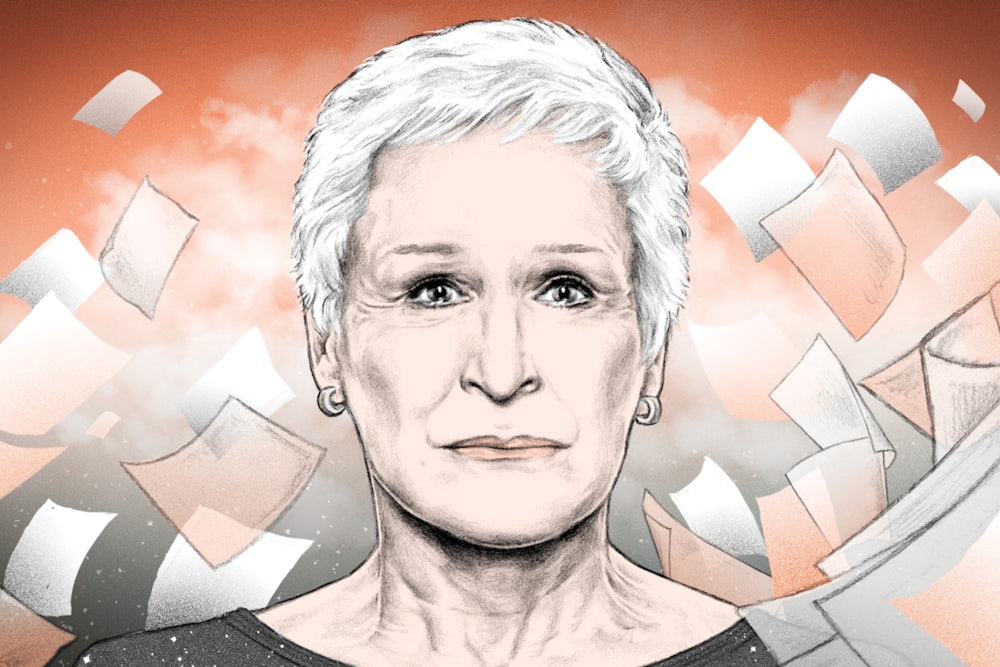

Björn Runge’s film The Wife attempts to penetrate that mystery and the enigma of creative genius by suggesting that, in order for good writing to take place, someone else—in this case, a woman—must not write, or must at least sacrifice her own talent to aid and abet male artistry. The film, which is based on a novel by Meg Wolitzer, with a screenplay by Jane Anderson, begins with an early morning phone call, disturbing the sleep of a close, upper-middle-class couple in Connecticut. The call comes from the Nobel Foundation in Sweden and brings news that the novelist Joe Castleman (Jonathan Pryce) has won the 1992 prize for literature. His wife, Joan (Glenn Close), seems as thrilled as Joe is, the two of them jumping up and down on their conjugal bed in celebration of a joint triumph.

Shortly thereafter the couple fly to Sweden on the Concorde, accompanied by their son, David (Max Irons), who is—but what else?—an aspiring writer in his twenties. He resents his father’s success and lack of interest in his own work and smolders accordingly when he appears. (Joe and Joan’s daughter, Susannah, appears in the film only briefly, caressing her pregnant belly.) Also along for the ride is Nathaniel Bone (Christian Slater), a journalist who plans to write the definitive biography of Castleman, with or without the writer’s agreement. Joe unceremoniously brushes Bone off when he comes over during the plane ride to offer his congratulations—although how a freelance writer could possibly afford a Concorde ticket is left unexplained. Joan is more polite, engaging in wary conversation. “There’s nothing more dangerous,” she admonishes Joe, “than a writer whose feelings have been hurt.”

This dynamic will prove a defining feature of their partnership: Joe barges through the world, convinced of his own importance (except when he isn’t—“If this doesn’t happen,” he says right before hearing the Nobel news, “I don’t want to be around for the sympathy calls ... . We’re going to rent a cabin in Maine and stare at the fire”), while Joan brings up the rear, soothing bruised feelings and uncomfortable situations, making sure that the cheering and adulation go on.

From this point, the film moves back and forth, through a series of expertly rendered flashbacks, between the Stockholm ceremonies and the period, during the late 1950s and early ’60s, when Joe and Joan first met and their relationship took shape. We discover that the young Joan Archer (Annie Starke), a WASP-bred Smith College student, has writing aspirations of her own, as well as the talent to fuel them. One of her teachers, who happens to be the young Joe (Harry Lloyd), casts an admiring glance at both Joan’s looks and gifts, singling out her student writing for its promise. Jewish and driven, Joe comes from a Brooklyn-accented background, a difference that pulls the two together rather than dividing them.

After Joe’s first marriage ends, Joan and Joe move in to a Greenwich Village walk-up and set up la vie bohème. She goes to work for a publishing house, where she serves coffee to the all-male staff who discuss possible projects as though she weren’t there. Joe, meanwhile, is pounding the keys back in their apartment, and somewhere along the way Joan has the bright idea not only of presenting his manuscript to the publisher she works for but also of finding ways to improve it, first by skillful editing and then by wholesale ghostwriting. He has the big ideas; she has the “golden touch.” Thus begins Joe’s literary career, one that will see him, some 30 years later, as the subject of a cover profile in The New York Times Magazine after his Nobel Prize is announced. Joe, ever the unabashed egotist, frets about his image: “Is it going to be like one of those Avedon shots with all the pores showing?”

As it turns out, Joe’s anxiety is not entirely misplaced. Runge and The Wife’s cinematographer, Ulf Brantas, make frequent and telling use of close-ups, especially of Glenn Close. One of the joys of this film is in watching the different pieces of Joan Castleman’s complex character fall into place, which Close can telegraph with just a shift in her gaze or the set of her mouth. She looks out for both the big and small potential blunders with a kind of casual, humorous vigilance: “Brush your teeth,” Joan tells Joe, after one of their Stockholm events. “Your breath is bad.” “Do you think they noticed?” he responds. “No, they were too busy being awed,” she replies. But underneath her role as the Great Man’s Wife, we catch occasional glimpses of her resentment of Joe (her repressed fury at times recalls the unhinged character Close played in Fatal Attraction) and the pain of her deferred ambition. In a particularly poignant scene, Joan comes upon the roving-eyed Joe flirting wildly with the young female photographer assigned to trail him. Her wordless but clearly chagrined response speaks volumes.

Without making use of jagged editing or a handheld camera— indeed, the look of The Wife sometimes verges on the satiny—the film succeeds in inhabiting its characters’ insides as well as their outsides. Christian Slater does a lot with his limited on-screen moments, imbuing his huckster role with enough depth to suggest that there is a sliver of humanity in his perceptions. When he tells Joan, for instance, that he suspects she is more than just a compliant wife—that she may in fact have a great deal more to do with her husband’s success than she lets on—we get a sense of the canny intuition that exists alongside his Sammy Glick–like striving. The character of Joe’s son, David, is, by contrast, irritatingly one-note, and Pryce is less than persuasive in the role of the Noble Prize–winning author. He plays Joe as an amalgam of every schmucky, womanizing Male Writer out there, with a predictable and unappealing mixture of arrogance and insecurity, rather than as a particular writer with a particular set of attributes.

There is, it must be admitted, something over-programmatic— or, perhaps, emotionally over-spun—about The Wife, especially with regard to the pile-up of dramatic incident in its last half-hour, which sometimes makes it seem like Bergman Lite. Just as you’re beginning to see the Castlemans’ marital arrangement in a whole other light, a new plot twist comes along to divert you. Then, too (spoiler alert), I’m not sure that long-standing marriages, however compromised, fall apart from one minute to the next, no matter how incremental the process behind the ultimate moment of recognition.

I also don’t know if I entirely believe in the too-neat scenario at the heart of the film, which has Joan perform a kind of exalted form of altruistic surrender (to borrow Anna Freud’s resonant phrase) in exchange for proximity to “the literary life and the house by the sea,” as Joe puts it. It seems to me, especially given the decade of her young adulthood, that even a woman as privileged as Joan would have faced a whole gamut of setbacks and discouragements out in the patriarchal world—circumstances that would have made pursuing a career as a writer difficult. It’s too reductive, to my mind, to imply that she simply gave up her own drive and hopes for the sake of a man. “I love to write, it’s my life,” Joan says early in the film, but we don’t really see evidence of this. Among other things, we barely see her reading, except in the last scene—and reading is what writers do when they’re not writing.

“I don’t want to be thought of as the long-suffering wife,” Joan declares, but that is inevitably how Joe and we in the audience come to see her, at least at first. The Wife is that increasingly rare offering, a commercially viable film that also makes you rethink your assumptions about talent and who gets to wield it. It begins as a portrait of a seemingly conventional marriage, its comforts and compromises, and gradually builds to a portrait of one woman’s radical journey to self-definition. One might have wished for a slightly less heavy-handed storyline, one that offered a bit less “closure,” but there’s no gainsaying the power of the film’s last image: an empty notebook page that winks out at us, alluring as the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby, suggestive of all the voices that have not yet had their say.