The evening before Chad Baker died, his fiancée, Katie Offenburger, came home from her job as an account manager at a credit card company, let the dog out, and smoked a cigarette on the back porch of their three-bedroom house in Newark, Ohio. The couple had met in addiction recovery, and they had moved in together a few years after they got out.

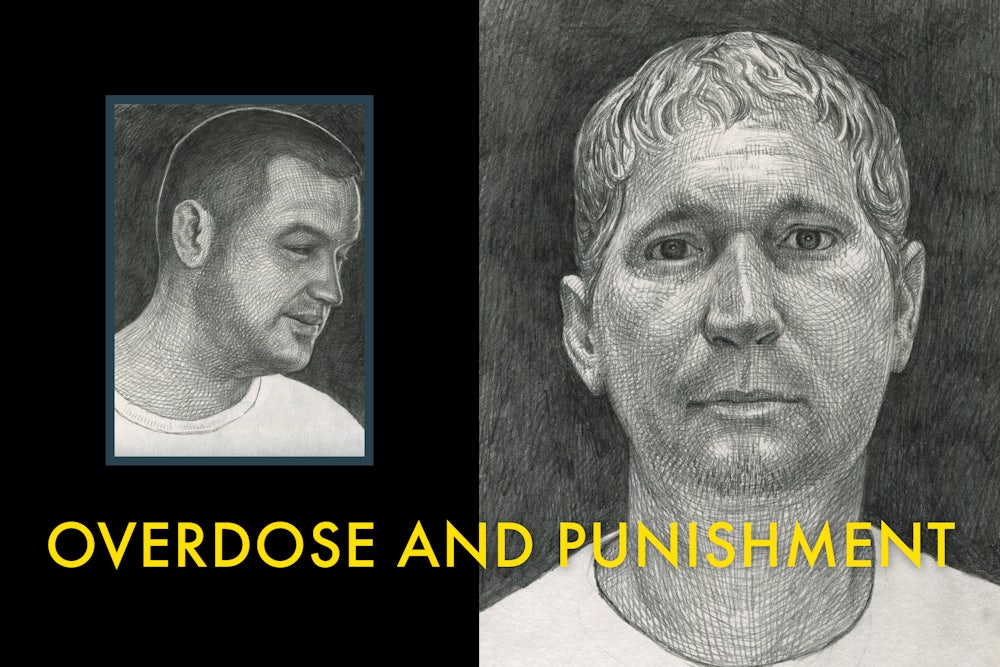

Offenburger, a petite woman with short, wavy brown hair, was tired but happy after a long day. She and Baker had both endured more than a decade of heroin addiction, recovery, and relapse—a cycle that, for Baker, included six months of incarceration. Now, however, Offenburger, who had turned 34 two months earlier, was more than three years sober, and Baker seemed to have turned his life around as well. He had a job as a plumber’s assistant, and his recovery, as far as Offenburger knew, was going well. Thirty-four years old, he was active in recovery groups, and his outlook appeared to be positive. In drug court, a diversion program that promotes treatment, drug testing, and social services as an alternative to prison, he met Aaron Campbell, an artist and Newark native, and the two became close friends. They bonded over their sobriety and shared love of basketball. They checked in on each other when they were tempted to use and watched games together whenever they could. One Sunday afternoon, Campbell fell asleep on Baker’s couch, a Cavs game on the television. Baker snapped a photo and posted it to Facebook: This is what true friends do, he wrote.

Baker and Offenburger’s relationship had deepened as well. They were raising their one-and-a-half-year-old child, and Offenburger was looking forward to their next phase together, which included getting married. With one caveat: There would be no wedding if they both couldn’t stay sober.

The next morning, Offenburger woke up and walked to the bathroom. The door was closed, but she heard water running. She knocked, but Baker didn’t answer. She pushed on the door, but it barely moved. Through the narrow opening, she could see Baker’s feet. She pushed hard and made her way in. “I saw Chad lying on the floor. There was a needle between his legs,” she later testified.

The paramedics who arrived on the scene at 7:46 a.m. found Baker unresponsive. His skin was pale, he had no pulse, and his pupils had shrunk to pinpoints. The paramedics performed CPR and attempted to revive him with epinephrine (adrenaline) and Narcan, a drug that blocks the effects of opioids, and then rushed him to the hospital, but he never recovered. Chad Baker was pronounced dead at 8:29 a.m. on May 29, 2015, three days before his birthday. A toxicology report subsequently revealed heroin and cocaine in his system.

Offenburger later testified that she thought Baker had finally put his drug use behind him for good, and that she didn’t know he had relapsed. “That’s not the life I wanted,” she said. “When we committed to each other, that wasn’t the life neither of us wanted.”

Two years later, Tommy Kosto sat in the Licking County Courthouse awaiting a jury’s verdict after a three-day trial. A 39-year-old white man with thinning blond hair, he wore khakis and a blue-and-white checked Oxford shirt, slightly larger than his slim frame. Baker and Kosto had met while serving time for drug offenses in a community-based correctional facility for nonviolent offenders about eight years earlier. Both were working toward sobriety while incarcerated. Kosto struggled, however, and by the spring of 2015, he was using heroin again, sending desperate, daily text messages to his dealer hoping to buy more.

But the county prosecutor alleged that Kosto wasn’t just a struggling user—he was a dealer and had sold Chad Baker the drugs that killed him. Kosto admitted to using heroin with Baker days before he died but denied that he sold the drugs that killed him. The jury sided with the prosecutor, finding Kosto guilty of involuntary manslaughter, corrupting another with drugs, possession of heroin, and tampering with evidence—for deleting text messages between himself and Baker. Together, these offenses could result in 15 years in prison. As the jury announced its verdict, Kosto wore a look of disbelief, and his attorney just shook his head.

Baker’s death was far from an anomaly in Licking County, Ohio, where 92 people have fatally overdosed since 2015. This story has played out across the country, as powerful synthetic opioids like fentanyl have entered the illicit drug supply chain, turning the opioid epidemic into what could just as easily be deemed an overdose epidemic. In 2016, the most recent year for which statistics are available, more than 64,000 people died from a drug overdose in the United States, a 21 percent increase over the previous year. It’s a crisis that has sparked national attention, yet no one, from federal officials to local politicians to public health organizations, has been able to curtail it. Ohio has been particularly hard hit. The accidental overdose rate in the state has more than tripled since 2000 and is the leading cause of accidental death for Ohioans under the age of 55.

The long-term economic and social impacts of the crisis on Ohio are stark. According to a report from the C. William Swank Program at Ohio State University, which focuses on rural-urban policy, the costs associated with treatment, criminal justice, and lost productivity in 2015 alone were between $2.8 billion and $5 billion. In Licking County, the number of children entering foster care increased more than 50 percent in 2017 compared to the previous year, the overwhelming majority of child removals due, at least in part, to substance abuse by their parents. Despite the depth of this crisis, the Swank Program notes, “in the best-case scenario, Ohio likely only has the capacity to treat 20 percent to 40 percent of the population abusing or dependent upon opioids.” This is due, in part, to a lack of regular access to medically assisted treatment for opioids—drugs like methadone and buprenorphine that can aid in recovery—especially in rural communities.

And in Ohio and across the country, as public health officials have struggled to address the opioid and overdose crisis, prosecutors have adopted a decidedly “tough on crime” approach. Increasingly, this has meant treating overdose deaths as murders and seeking to level harsh penalties against dealers, even small-time drug users like Tommy Kosto, who have supplied people with the drugs that killed them. The federal government and 20 states currently have what are known as “drug-induced homicide” laws on their books, under which anyone involved in the illegal manufacture, sale, distribution, or delivery of a controlled substance that causes death can be charged with murder or manslaughter. Last year, 13 additional states introduced bills to create or increase penalties for drug-induced homicide offenses. Midwestern states, including Ohio, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota, have been among the most aggressive in prosecuting drug-induced homicides. According to a New York Times investigation, there have been more than 1,000 prosecutions or arrests in connection with accidental overdose deaths since 2015 in 15 states where data was available. News reports about drug-induced homicide prosecutions have also spiked, with cases documented in 36 states. The use of drug-induced homicide laws “has already skyrocketed in the last three to five years,” said Leo Beletsky, associate professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, “and it’s going to continue increasing substantially.”

While this trend began prior to Donald Trump’s election, it has accelerated since he assumed office. According to the United States Sentencing Commission, a federal agency, there was a 10 percent increase in 2017 in the number of people who received federal prison sentences for distributing drugs resulting in death or serious injury and a nearly 200 percent increase since 2013. Trump has made it clear that he favors an aggressive approach to the opioid crisis. “My take is you have to get really, really tough—really mean—with the drug pushers and the drug dealers,” Trump said in February, during a speech in Blue Ash, Ohio.

Trump has pushed this rhetoric to its logical conclusion, suggesting that drug dealers should face the death penalty, an idea he said he got from Chinese President Xi Jinping. He has also expressed admiration for President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines for his violent approach to curbing drug trafficking. In March, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memo to the 93 U.S. attorneys reminding them that they have the power to pursue capital punishment in certain drug-related cases.

This aggressive approach has filtered down to the local level. In Ohio, residents have ample reason to be frustrated with the bodies piling up in the state’s morgues; the strain on health care, police and emergency services, and the workforce—a cost of up to billions of dollars every year; and the emotional pain it’s causing families. Last summer in Middletown, Ohio, a city of 50,000 near Cincinnati, city council member Dan Picard proposed a three strikes policy for overdose rescues. Overdose victims would be required to perform community service to make up for the cost of treatment—and if a 911 dispatcher determined that someone who was overdosing had not performed community service, they would not dispatch emergency services. “We’ve got to do what we’ve got to do to maintain our financial security, and this is just costing us too much money,” Picard told a local news station. First responders balked at the proposal, but the anger that bred it persists. Stickers that say SHOOT YOUR LOCAL HEROIN DEALER have started to appear on truck windows around the state. In Summit County, where the opioid crisis is so bad they have had to use refrigerated trailers as morgues, prosecutors have charged 49 people with manslaughter in connection to an overdose since 2014. And in Licking County, at least four people in addition to Tommy Kosto were charged for supplying drugs that led others to overdose between 2016 and 2017.

After Kosto was convicted, prosecutor Bill Hayes told The Newark Advocate that drug-induced homicide laws would help stem the opioid crisis in Ohio. “The jury sent a strong message that cavalier use of drugs in our community isn’t going to be tolerated,” he said.

The concept of prosecuting individuals in connection with drug-related deaths goes back more than a century. In 1885, a doctor in New York was charged with manslaughter after a patient died from a morphine overdose. The doctor was accused of administering the drug “with wicked, wanton, willful, and reckless disregard of the life of the patient.” In 1916, less than two years after Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act, which regulated the sale of opiates and coca products, three people were arrested in connection with the death of a 15-year-old boy who died of a heroin overdose. And in 1970, a Bronx grand jury indicted two men for second-degree manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide for giving heroin to a 17-year-old Barnard freshman.

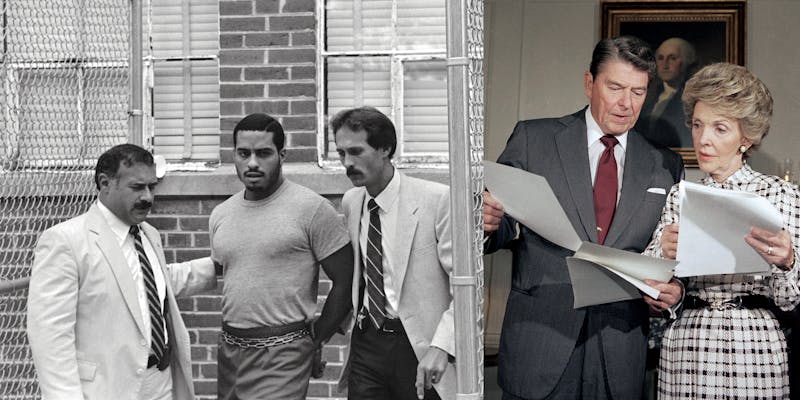

Many drug-induced homicide laws date to the 1980s, however, when states and the federal government used them as part of the war on drugs approach to the crack cocaine epidemic. After University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose in June 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which mandates a sentence of 20 years to life in prison for dispensing a controlled substance that results in “death or serious bodily injury.” Eleven of the 20 states that have such laws passed them in the 1980s and early 1990s. Penalties for charges under the state laws range from two years in prison to capital punishment, which is the case in Florida and Oklahoma. (To date, no one has been sentenced to death in a drug-induced homicide case.) In six states—Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and West Virginia—the minimum sentence for a drug-induced homicide conviction is life in prison. Despite their creation as a knee-jerk response to a social crisis, however, these laws were rarely used for decades. That is changing.

Leo Beletsky said that, in many ways, drug-induced homicide prosecutions are a form of political theater: “It’s an episode out of a multiseries sort of American story.” Passing these laws and prosecuting individuals under them might help lawmakers and prosecutors burnish their tough-on-crime bona fides. But there’s no evidence that stiffer penalties have reduced drug overdoses. A recent report by the Pew Charitable Trusts points out that there’s no relationship between drug imprisonment rates and a state’s drug problem. “The theory of deterrence would suggest, for instance, that states with higher rates of drug imprisonment would experience lower rates of drug use among their residents,” the report notes. But according to the study, incarceration is one of the least effective methods for reducing drug use and crime. “With addicted people, it doesn’t deter behavior or deter people who have multiple felonies and can’t do anything else to make a living,” said Kathie Kane-Willis, director of policy and advocacy with the Chicago Urban League, who has been tracking the outcomes of Illinois’ drug-induced homicide law since the early 2000s.

And yet, incarceration is still a common method for addressing America’s addiction crisis. One in five of the almost 2.3 million people currently in prison in the United States is there because of a drug-related offense. Most of these people are not violent drug kingpins; mandatory minimum sentencing laws have filled jail cells with low-level drug offenders—primarily minorities. African Americans make up 40 percent of those incarcerated in the United States, despite being 13 percent of the population.

Kosto and Baker are both white, and the prevailing narrative around the opioid crisis is that it is a white problem. This isn’t factually the case, of course—the prosecution of drug-induced homicides is likely to affect minorities disproportionately. African Americans are dying from opioid overdoses at a rate higher than the general population in a number of states, including Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, Minnesota, and West Virginia. In Illinois, deaths from opioids among African Americans increased by 123 percent from 2013 to 2016, faster than for any other racial group. And as Kane-Willis from the Chicago Urban League told me, as the opioid crisis spreads, and drug-induced homicide prosecutions become more common, even more people of color are likely to go to prison.

Moreover, while many states, including Ohio, have Good Samaritan laws that are meant to encourage people to call 911 if someone appears to be overdosing, the fact that you could be charged with manslaughter discourages some users from seeking help. In a 2017 study, Johns Hopkins public health researchers Amanda Latimore and Rachel Bergstein found that some drug users said they would hesitate to call 911, or not call at all, in part because they feared being charged with the person’s death. Illinois law specifically includes language that says it will not protect individuals from drug-induced homicide charges. Health workers in Licking County told me anecdotally that the local emergency room sees just as many overdose victims being dropped off as being transported by ambulance—likely because people are afraid to call 911.

Drug-induced homicide laws are supposed to fight serious drug traffickers, the people responsible for so much misery and death, even if they don’t know their victims personally. For example, New Jersey’s 1987 statute targets “upper echelon members of organized trafficking networks,” and 1988 legislation in Illinois was aimed at large-scale drug suppliers. “It is time we treated drug traffickers, suppliers, and dealers as the murderers they are,” said Democrat Emil Jones, who sponsored the bill. In 2003, Vermont used similar language, claiming its law targets “entrepreneurial drug dealers who traffic in large amounts of illegal drugs for profit,” rather than users who sell to support their habit.

In practice, however, the laws often lead to prosecutions against friends and family members. Twenty-five of 32 drug-induced homicide prosecutions identified by the New Jersey Law Journal in the early 2000s involved friends of the person who overdosed rather than “upper echelon” traffickers. In 2016, Jarret McCasland of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was sentenced to life in prison after his girlfriend died of an overdose following a day the couple spent shooting heroin together. That same year, Lindsay Newkirk injected heroin into her arm and then into her father’s arm in a motel on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio. When she woke up hours later, her father was dead. Facing more than eleven years in prison for involuntary manslaughter and corrupting another with drugs, she pleaded guilty and is serving a three-year sentence. Later that year, too, Samantha Molkenthen, a young woman in Jefferson County, Wisconsin, was sentenced to 15 years in prison for delivering the drugs that led to the overdose death of her friend Dale Bjorklund.

Last year, an investigation by a Fox News affiliate in Wisconsin into 100 drug-induced homicide prosecutions in the state found that in nearly 90 percent of the cases, the people charged were either low-level street dealers or friends and relatives of the person who overdosed. According to Lyndsey LaSalle, senior staff attorney at the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy organization focused on ending the war on drugs, one reason the last person who touched the drugs is typically charged is because it’s easier to get a conviction. “The further you get up the supply chain and the further removed you get from the actual hand-to-hand sale or exchange, the more difficult they become” to prosecute, she said.

Leo Beletsky agrees. “You can’t typically make the case stick with someone who is two, three orders removed,” he said. “They’re going after co-users, who are often also dealers, and the idea that you can distinguish between the two is based in a willing sort of denial of how drug markets work. Prosecutors and cops know this, but they talk about it in a different way than what they understand to be reality.”

In the case of Tommy Kosto, the Licking County assistant prosecutor, Clifford Murphy, asserted that Kosto had deliberately targeted Chad Baker. Kosto, he argued, knew that Baker was doing well with his sobriety but wanted to get him using again to help support his own habit. “He set out to infect somebody, or reinfect somebody, who had already been through most of the disease,” Murphy told me.

For Douglas Berman, a law professor at Ohio State, this is the crux of the problem with how the government allocates resources and what public officials emphasize in the rhetoric around the opioid crisis. “Lots of drug dealers are actually themselves addicts and struggling with a range of social and personal issues,” he said. “They’re not intentional killers. They’re not involved in the kind of vile and venal behavior that produces the labels and the sentences that we think the worst of the worst criminals ought to get.”

According to Billy McCall, a former DJ and construction worker who knew both Kosto and Baker from the same community-based correctional facility, and who is also in recovery, Kosto’s intentions were far from sinister: He was simply a drug user engaging in typical user behavior. In Licking County, he said, that can mean pooling money and driving to Columbus, Ohio, to buy cheaper heroin and picking up a little extra for four or five other people. Today you help them out; tomorrow they help you out. McCall also said that one of the main reasons users feel compelled to buy and share drugs is that they know what it means to go through withdrawal. He recalled a time when he and Baker were working together assembling grills and bicycles for Walmart in Western Pennsylvania. They were both sober at first, but after a while they began using again. “At times,” he said, “if we were sick, and we couldn’t get nothing there, we would drive all the way back to Columbus, a five-and-a-half-hour drive, grab our stuff, and then go all the way back.” Understanding the pain of withdrawal explains why users might help each other get drugs, even though that in and of itself is a crime, McCall said. “If you’re compassionate, if you’re a human, you wouldn’t want to see anybody go through that, you know?”

McCall’s story also highlighted the capricious manner in which overdoses become crime scenes, and in which drug-induced homicide prosecutions can be pursued. He was once charged with abusing harmful intoxicants in Pike County, Ohio, after an overdose. Several years ago, however, McCall and his girlfriend, Michelle, bought some heroin together and shot up in her car, in the parking lot of a Columbus-area Nordstrom. She initially said the drugs were good. They stepped out of the car to take in the beautiful July day. “I gave her a big hug and said, ‘Let’s go to Newark,’ ” McCall said, but she suddenly collapsed on the ground, overdosing. “I remember saying, ‘Michelle, I’m gonna have to call the squad if you don’t start breathing,’ ” McCall said, before he, too, lost consciousness. “Then I came to, and I’m spread out, and there’s all kinds of paramedics around me.” Michelle died. Unlike Tommy Kosto, McCall faced no charges.

At Tommy Kosto’s sentencing hearing last July, Clifford Murphy, the assistant prosecutor, pointed out that Kosto had been in the court before and had been given multiple chances to turn his life around. This time, he asked the judge to “impose a prison sentence that will deter other people from similar type conduct”—a sentence “consistent with the expectation that the community should be aware that people that are going to participate in these endeavors, especially when someone dies, are going to be held accountable.

“We’re asking that this court send a strong message through a serious prison term for Mr. Kosto,” Murphy told the judge.

According to Leo Beletsky, handing down harsh prison sentences will do little to address the current addiction crisis. It is simply an emotional response, he said, by people who are looking at a crisis and seeking a quick solution. If the goal is to reduce overdoses, Beletsky told me, then the state has to approach the problem differently. “We’ve had these laws, and we have more people on drug-related charges behind bars, per capita, than any other nation on earth, currently, and yet heroin is more widely available and cheaper than it’s ever been,” he said. It would be much more effective to focus instead on harm reduction—measures that seek to change user behavior and save lives.

The grassroots Ohio Safe and Healthy Communities Campaign has backed a constitutional amendment that would reclassify the lowest-level drug felonies as misdemeanors and call for more state funding for treatment. The amendment will be on November’s ballot. Groups like Harm Reduction Ohio are advocating for syringe-exchange programs throughout the state. And in Licking County, a Quick Response Team, made up of people representing law enforcement, treatment providers, and peer support groups, is trying to intervene with overdose victims. But more resources are needed. If people are overdosing around loved ones, that’s a sign that a community could use better access to Narcan so that people can be quickly revived and have access to treatment, a policy Surgeon General Jerome Adams and others have called for. But programs like these require funding, as well as a dramatic transformation in the country’s approach to addressing addiction—and that hasn’t happened. Every dollar that goes to a drug-induced homicide prosecution is a dollar not going to support harm reduction or treatment.

In the Tommy Kosto case, Judge David Branstool addressed the court before issuing his sentence in July 2017. “I knew Chad Baker,” Branstool said. “He graduated from the drug court probably three or four weeks before he OD’d. He was a drug addict, and he relapsed. Tommy Kosto is a drug addict ... probably one of the most severe addicts I’ve ever come across.”

At Kosto’s sentencing, Chad Baker’s father, Jeff Baker, a thin and energetic man in his late fifties, choked up as he talked about how much his son’s death had disrupted his close-knit family. But he also hinted at some ambivalence about the outcome of the trial. Standing in the wood-paneled courtroom, his hands shaking as he held a piece of notebook paper in front of him, he said, “There are no winners in this matter, but me and my family never get to spend time with Chad.”

Jeff Baker told me that after his son died, he wanted Kosto to receive a harsh sentence. When I spoke to him after Kosto’s sentencing, though, he said he wasn’t sure. Baker said he no longer felt any animosity toward Kosto.

“My family would probably hate to hear that,” Baker said. “There is no justice, to be honest. I don’t think so. My honest opinion, my son would tell you, ‘Leave these people alone. I made the choice on my own.’ He would, I know he would.”

Baker told me that coming to terms with his son’s death is also about coming to terms with his son’s addiction and what he said was his choice to take drugs that day—or rather, he added, the fact that the drugs made the choice for him. “Tommy is sitting in prison because he broke the law. That’s the way I look at it,” Baker told me. “Did he kill my son? No. He broke the law.”

Branstool sentenced Kosto to a mandatory four-year prison term, plus one additional year, a fairly lenient sentence. In May, however, the Ohio 5th District Court of Appeals found there was not enough evidence to convict Kosto of involuntary manslaughter and corrupting another with drugs. Baker had died from a combination of heroin and cocaine, but Kosto had been charged with supplying only the heroin. The other two convictions still stand, and Kosto will serve another year while the prosecutor appeals the appellate court decision in the state Supreme Court. At his resentencing, Kosto told the court, “I just want this nightmare to be over.”

Meanwhile, the overdose crisis in Licking County, Ohio—and around the country—has continued unabated. If drug-induced homicide prosecutions are intended to send a message to dealers, there is no discernible evidence that it has been received. Nor has there ever been such evidence. In a speech at the White House on August 4, 1986, as lawmakers in Washington wrestled with how to address the drug crisis in the wake of Len Bias’s fatal overdose, President Ronald Reagan acknowledged that it would take more than criminal prosecutions to win the war on drugs. “We’ve waged a good fight,” Reagan said. “Drug use continues, and its consequences escalate. All the confiscation and law enforcement in the world will not cure this plague.”

That is as true today as it was three decades ago. And as is the case today, when Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act into law that October, political theater won out over rational thinking. Out of the law’s total $1.7 billion budget, $1.1 billion was allocated for law enforcement: more boats, planes, and weapons with which to fight drug traffickers on land, sea, and air; more federal agents and boots on the ground in the ever-expanding drug war—and, tellingly, more prosecutions and more jail cells.