For Democrats, the stakes for this year’s congressional elections have risen more dramatically than anyone could have foreseen even just a short time ago. All the weighty factors are still there—the Trump administration’s nepotism, corruption, and obstruction; its stacking of the judiciary; and its frenzied stripping of the bark off the welfare state. But after Donald Trump’s meeting in Helsinki with Russian President Vladimir Putin this summer, it has also become apparent that the president of the United States is an agent—or at least an overexcited fanboy—of a foreign adversary. And his party, despite occasional noises to the contrary, doesn’t seem inclined to do a thing about it. If ever America needed a big, earthshaking election to change the course of the country, it’s now.

Much of the time, in big, earthshaking congressional elections, Democrats have gotten hammered. First there was 1994, the so-called Gingrich Revolution, the year of the GOP’s Contract With America, when Republicans gained 54 House seats and took control of that body for the first time in 40 years. The country was dissatisfied with an economy that had yet to soar to the heights it did in the late 1990s and nettled by a sense that Bill Clinton’s presidency had meandered until the day Hillarycare finally crashed on Bob Dole Rock.

In a similar vein there was 2010, the year of the Tea Party revolt. This time, a Democratic administration managed to pass health care reform, but that just made Americans—or midterm voters, anyway—even madder than the 1994 failure. That and a lousy economy gave the GOP a net pickup of 64 seats and control again after a short, four-year Democratic regnancy. Finally came 2014. Maybe not big and earthshaking numerically, as the GOP gained just 13 seats, but it was depressing out of proportion to its numbers, as it ensured that Barack Obama would pass no major legislation during his final two years in the White House and that House Republicans would use that time trying to destroy Hillary Clinton. Plus, the continuing GOP Senate advantage meant Obama would have trouble with a Supreme Court nomination should a seat open up (how much trouble, no one could have imagined in November 2014).

Only once in the last three decades have Democrats had a satisfying midterm election in 2006, when they picked up 32 seats and won back House control for the first time since the pre-Gingrich days. Any George W. Bush agenda was dead in the water, and Denny Hastert, the GOP speaker who was not yet known as a child molester but who’d imposed that odious and polarizing rule about never bringing a bill to the floor that didn’t have a majority of Republican support, had been replaced by Nancy Pelosi. But even it wasn’t quite huge. Thirty-one seats were enough to change the signs on the doors, but it wasn’t the kind of thumping the GOP had given the Democrats in ’94.

For a taste of that, we must go all the way back to the midterm elections of 1974. The Vietnam War ground on, a year after Henry Kissinger won a Nobel Peace Prize for ending it. The OPEC oil embargo had come and gone, and gas prices—few Americans had ever given the price of a gallon of gasoline a moment’s thought before the fall of 1973—had more than doubled. And, of course, there was Watergate. On May 9, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee under Democratic Chairman Peter Rodino of New Jersey opened its hearings. Over the summer, it took testimony from a parade of Nixon aides and finalized three articles of impeachment in late July. In August, Nixon surrendered his tapes. Three months to the day after the Judiciary Committee hearings opened, Nixon resigned. He was at 24 percent in the polls. On September 8, new President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon, which destroyed whatever goodwill Ford had earned. The Republicans were shipwrecked. There was so much blood in the water it was practically more blood than water.

There was very little of the fancy election forecasting that we have to such excess today. But even so, people knew. In an April special election, a Democrat named Bob Traxler beat a Republican in a district in Michigan that hadn’t elected a Democrat since 1932. The day after that election, Michigan GOP Senator Robert Griffin said: “No Republican should assume he has a safe seat anymore.”

None did. When the votes were counted, Democrats had netted 49 seats, but because of retirements and primary wins by upstart challengers, they sent 76 new members to the next Congress, the ninety-fourth. Few Democrats anywhere lost—although one who did, by just about 3.7 points to a Republican incumbent, was a young Arkansas comer named Bill Clinton. (Interesting to ponder how his history, and Hillary’s, and the country’s, would have been different if 3,000 voters in Arkansas’s third district had voted differently.) But that one aside, the country elected Democrats from all manner of places that sound impossible today: Wyoming, Utah, Montana; Oklahoma and rural Missouri; 21 out of 24 districts in Texas. The Democrats already had a majority of 243 seats, but now that shot up to 291. They added one more seat in the next Congress, and neither party has boasted such an impregnable majority since.

Today, Democrats are dreaming of their own class of “Watergate babies,” as these new freshmen were quickly dubbed by the pundits of the day. Looking ahead to the midterm elections, many forecasters believe the Democrats will gain the two dozen seats they need to win back control of the House. Some say they’ll win many more—as many as 50 or so, which would bring the party up to controlling around 240 seats and give it a cushion of around 30 votes heading into the 2020 elections, when (most experts assume) turnout among the Democratic base will be even higher. The circumstances today are not in fact as favorable as then—Trump’s approval rating is 15 or so points higher than Nixon’s was in 1974, and today’s economy is rolling along pretty nicely, in contrast to 1974’s punishing 8.3 percent inflation. But Trump’s approval numbers are still consistently in the red. That, plus the ceaseless scandal news and the results of nearly every special election so far, has Democrats thinking big.

In such an environment, it’s natural to think back to 1974. Can the class of 2018 go down in history in anything like the way the ’74 class did? It’s doubtful. Times have changed. The House isn’t what it was in the 1970s—that is, an institution that wasn’t yet horribly polarized, that took the country’s problems seriously and actually tried to address them through compromise. But that isn’t to say that a large freshman Democratic class can’t start making a difference in 2019. They can, and to do so, they should take a little time to learn from their elders.

To understand the impact of the Class of ’74 on the House, it’s important to get a handle on what the place was like before they came along. Vast changes had convulsed the nation for the previous decade: civil rights, women’s rights, rock and roll, long hair, drugs, television shows acknowledging the existence of things like sex. A completely different country from the one that had made Andy Williams a pop star a decade before.

But in Congress—there, there had been some change. A decade earlier, liberal Democrats and moderate Republicans had managed to break the power of the racist chairman of the House Rules Committee, Howard Smith of Virginia, so that Congress could finally consider civil rights legislation. Over the course of the ’60s, enough liberals were elected to begin to foment for more internal reforms, and the speaker, John McCormack of Massachusetts, not exactly a liberal but also not a reactionary, even granted some minor ones, like scheduling more meetings of the Democratic caucus. And from 1970 to 1973, the caucus began to chip away at the seniority system—a 1973 change, for example, allowed for a secret ballot on appointing chairmen, but only if one-fifth of the caucus pushed for it.

In essence, though, the House of Representatives of 1974 was still a plantation. Or more accurately, half plantation, half Politburo. Its mores and folkways were intensely Southern, from the predominantly African American (back then) employees at the House cafeterias to the more consequential matter of the way the House ran the District of Columbia. And it was a Politburo in that a small handful of committee chairmen ran things. They were all Democrats, yes, but they sure weren’t liberals. Many were Southerners, racists and segregationists, and quite conservative. Committee chairs were awarded strictly on the basis of seniority, and once someone got that chairmanship —and they were mostly men, too—he often had it for life. “For many of them, that was the only reason they were Democrats,” recalls Henry Waxman, the long-serving Los Angeles congressman who was part of the 1974 class.

The chairmen ran their committees in completely autocratic ways. Carl Vinson, the Georgian who had served since 1914 and chaired the Armed Services Committee for 14 years, allowed committee members to ask one question at hearings per number of years that the member had served—and Vinson got to approve all questions in advance. On the floor, things weren’t much better. In those days before electronic voting, most votes were taken in secret, as John A. Lawrence writes in his new book, The Class of ’74:

Rather than publicly declaring their positions, individuals would “walk the gauntlet of the tellers,” or designated clerks, to record their votes. While waiting in line, members often would be accosted by a chairman or other influential member of the committee whose bill was being considered. “You want that bridge in your district?” the member would be asked. “You’re not voting for this.”

And so it went. The liberals who existed got some change through, but there just weren’t enough of them. They had sought, for example, to oust the openly racist chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia, John McMillan of South Carolina, in 1971. (Yes, the chairmanship of the D.C. committee was typically given to a Southern racist.) Among his other shocking acts, McMillan had responded to the city’s first-ever self-generated budget request in 1967 by sending appointed Mayor Walter Washington, who was black, a truckload of watermelons. In what we might fairly acknowledge to have been a slight excess of optimism, the liberals wanted to replace McMillan with Charles Diggs, a black member from Detroit. This was too much for Wilbur Mills, the (Southern) chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, who warned that such a move would risk alienating the Southern vote in the 1972 elections. So the racist stayed in place. The liberals were again reminded, Lawrence writes, that Democratic control of the House “rested in large part on maintaining the seats of conservative southerners.”

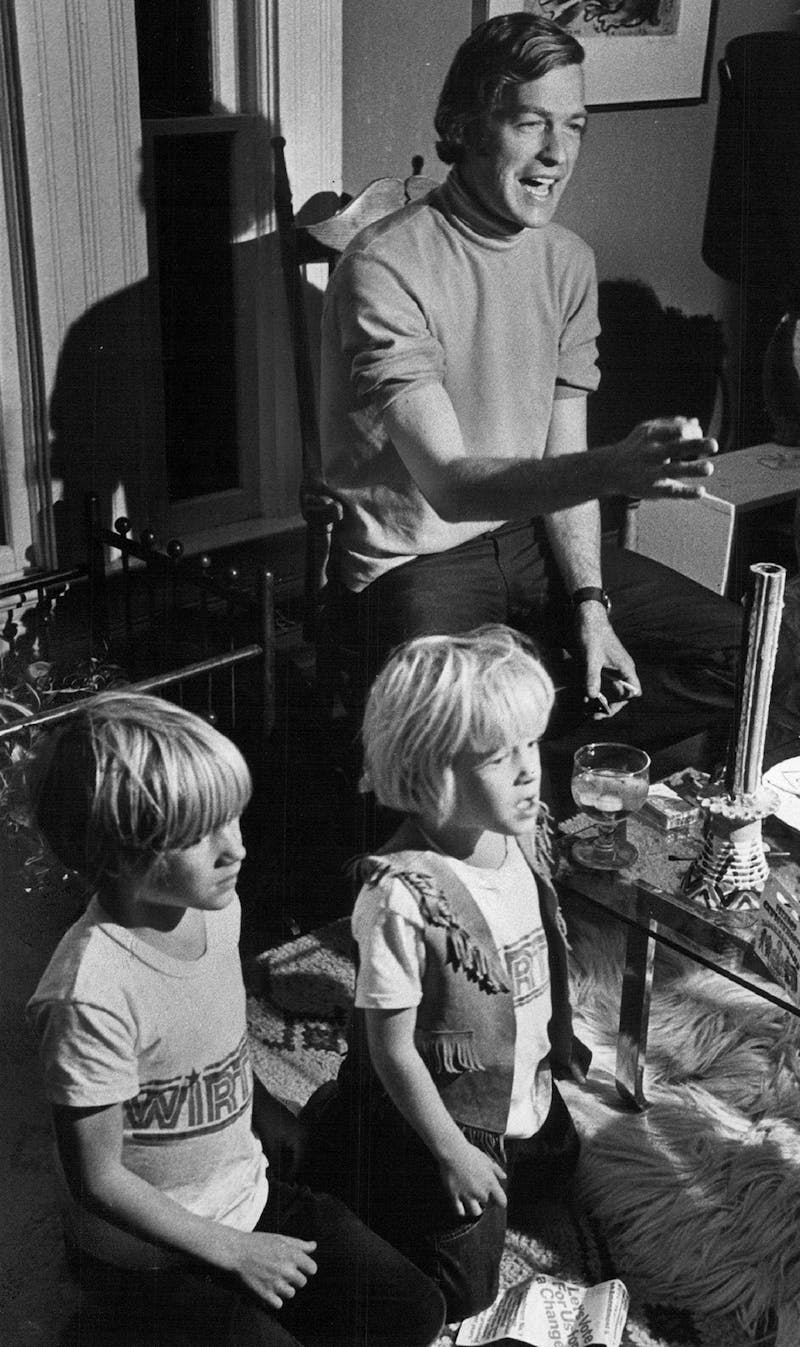

This was the milieu into which these 76 new members charged. They were young. They were smart. They were dedicated to reform and to broadly liberal causes. They looked different. Go find a circa-1975 picture of Toby Moffett, one of the class’s young stars, at 30. He looks every inch the Nader’s Raider he was, or like he played bass for Gordon Lightfoot. They were also, incidentally, male: The group included just four women, who (along with the three Republican women elected in 1974) joined the twelve already there—a small number, though it included some historic figures, such as Elizabeth Holtzman, Bella Abzug, and Patricia Schroeder.

And most of all, they were brash. Moffett beat a pro-war Democrat in the primary and then faced an Italian-American opponent in his western Connecticut district, a man named Patsy Piscopo. He demanded a debate at the Sons of Italy hall. What, his friends asked him, are you thinking? But Moffett had a trick up his sleeve. “You walked up what seemed like a thousand steps, you know, those old buildings,” he recalled to me. “Way, way up.” All men, all Italian, all head-to-toe in black. The room was ice-cold to him. Then he started to speak. “I gave my whole thing in Italian, because I had studied in Firenze,” he told me, smiling mischievously. “And it was, like, the white flag of surrender. [Piscopo] looked at me like ‘you mother-fu–’ … you know.” Moffett won a crushing victory: 63 percent of the vote. “They looked at me as a long-haired, left-wing guy not connected to the community,” he said. “But I was basically an urban ethnic product, and I had energy. I had labor. I had anti-Vietnam. I had the beginning of the women’s movement. I had the fallout from Earth Day, the positive fallout.”

Not everybody had a district like Moffett’s, who came to number among his constituents and friends Philip Roth, William and Rose Styron, Arthur Miller, and Leonard Bernstein. Phil Sharp in Indiana was running in a basically Republican district, so he played his anti-Nixon stances down a bit. “Frankly, I don’t think I ever said much about Watergate,” Sharp recalled. “We were in Nixon country, and people were behaving at first like Trump people now: ‘Well, no, this is not true,’ or ‘That’s what they all do.’ ” After losing narrowly to a Republican incumbent in 1970 and 1972, he finally beat him by nearly 9 percent on the third try.

Despite the class’s reputation as a bunch of crazy liberals, it included a number of moderates it elected as its president Carroll Hubbard of Kentucky. But liberal or moderate, from Los Angeles to Kansas to South Carolina, they all rode the same wave. “I didn’t believe that Watergate would carry this far,” said New Jersey Republican Charles Sandman, a four-term incumbent who got clobbered by Democrat William Hughes, “but it has, and there is nothing I could do about it.” Democrats of all ideological stripes won—upstart liberals, who beat entrenched incumbents in districts that were then reliably Democratic and union-heavy, but also a good number of moderates from purple districts. And all were needed in order to push through reforms. Today’s Democrats would do well to remember this as they fight over the party’s ideological identity.

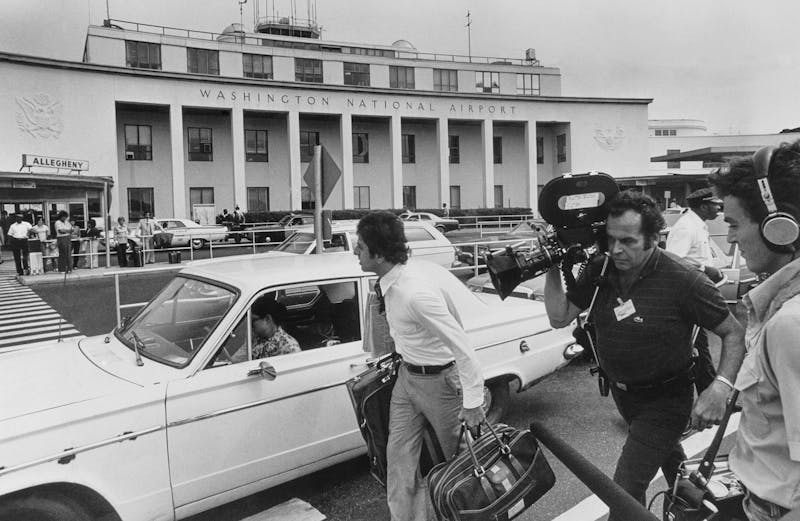

The incoming Democrats began to head to Washington, recalled Tim Wirth of Colorado, another of the class’s big stars, shortly after Election Day. “A couple days after the election, I went in to see [Speaker] Carl Albert,” Wirth said. “He said, ‘Go see Sparky Matsunaga, he’ll fill you in on where to park, what your salary is, all that stuff.’ ” Wirth laughed; getting parking and salary instructions from the House member in charge of such matters wasn’t the kind of conversation he and his classmates had in mind.

They assembled in late November and put together a list of reform demands. Item number one: the committee chairs. They wanted the caucus to have the right to an automatic vote on all chairmen every two years—and on a secret ballot, so the votes against the old bulls would be consequence-free. They got a vote and the secret ballot. “We began caucusing, and we got to know each other, we asked what people were interested in, and we stayed together,” said Sharp, who became another of the class’s standouts. “And so somebody in our class came up with the idea: Well, we ought to hear from these people we’re gonna vote on. Ha! Well, let me tell you, that was revolutionary; that was explosive. Are you kidding? Nobody talks to freshmen, or barely does, let alone goes to sit and answer questions from them.” Most of them did, even though, as Waxman put it, “Some of them just looked very disdainful of meeting with a bunch of kids.” Three were bounced: Edward Hébert of Armed Services, William Poage of Agriculture, and Wright Patman of Banking and Commerce (Louisiana, Texas, and Texas).

One who survived was Harley O. Staggers, who chaired the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee (Energy and Commerce today): then, as now, an extremely powerful committee with broad jurisdiction. All four of the young stars I interviewed—Moffett, Sharp, Waxman, and Wirth, all of whom still live in Washington and remain politically involved to varying degrees—landed coveted spots on the committee. None of them hated Staggers. He was a nice man, and he wasn’t a segregationist—he was from West Virginia, which was not the South in those days, and he’d voted for the civil rights and voting rights bills.

They didn’t challenge his committee chairmanship. However, there was a subcommittee on oversight, and that’s what they set their sights on. The subcommittee had much potential power, but Staggers, who chaired it as well as the full committee, didn’t use it. John Dingell, a senior and influential committee member, backed John Moss of Sacramento for the post. Staggers fought hard to keep it. Sharp recalled that the chairman offered to give him any subcommittee he wanted, which just made Sharp laugh because that wasn’t a power chairmen had anymore. Waxman remembers Staggers pleading with him—a freshman—and describing himself as “a good Christian.” “And I thought that was a very peculiar argument to make to me,” said Waxman, who is Jewish. “To him it just meant ‘I’m a good guy, I’m a good person.’ ” A source who was a young committee aide at the time said the atmosphere at the committee’s Rayburn Building rooms was extraordinarily tense and recalled there being more than 20 ballots before someone switched votes to break the deadlock and hand the subcommittee to Moss. Staggers served through 1980, and Dingell took over from there.

That subcommittee fight was important and illustrative, because it represented a broader shift that was probably the most fundamental change effected by the class: Power moved from committees to subcommittees, and subcommittee chairs for the first time got to set their own agendas and hire their own staffs. “What happened was the real democratization of the House,” said Wirth, who is now vice chairman of the board of the United Nations Foundation and the Better World Fund. “It was a really wonderfully operationally democratic institution. Tip [O’Neill, the majority leader at the time] gave people an enormous amount of running room. The subcommittees were extraordinarily active. It was a legislative body really reflecting the country. Finally.”

The House had started to democratize and liberalize before this class got there—all four of these men took pains to point that out. Much far-reaching legislation was passed from the mid-1960s through the early 1970s, from civil rights and voting rights to housing to the Freedom of Information Act (the work of John Moss) to the Clean Air Act. But the Watergate babies made a critical mass; with them, there was finally more energy going into crafting liberal legislation than blocking it. The ninety-fourth Congress passed automobile fuel efficiency standards, a major first. It passed a law ensuring a proper education for children with disabilities. It passed several pieces of conservation-related legislation. The class of ’74 built on the work of prior Congresses, passing important amendments in 1977 to the Clean Air Act, a process Wirth, Waxman, and Moffett helped shepherd. And on foreign policy, Congress in 1975 refused President Ford’s request for $300 million in emergency funds for the Vietnam War, which built on the 1973 War Powers Act in finally bringing that war to an end.

Wirth served in the House until 1987 and then one term in the Senate. Moffett served four terms in the House and ran for Senate in 1982, losing to the liberal Republican incumbent Lowell Weicker. Sharp stayed in the House until 1995, getting out just before the members of the Gingrich landslide assumed office. And Waxman, of course, stayed for 40 years. “That class produced seven or eight legislative giants of the last 50 years,” said Moffett. “Henry Waxman on health care. George Miller on education. Tom Downey on arms control. Tom Harkin on disabilities. Chris Dodd on Dodd-Frank. I remember thinking, this is just ... how did I become part of this?”

This summer, Democratic voters across the country are choosing their nominees in primaries. By Labor Day, most of the specific match-ups will be known. Last year, a spokeswoman at the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee told me that candidate recruitment has been like nothing they’ve ever seen—that they have good, plausible candidates in 70 or 80 districts.

Of course, things could always go wrong. While Trump’s approval rating is low, it’s not as low as it feels like it ought to be. If the economy keeps chugging along, if peace breaks out on the Korean peninsula and Trump is legitimately seen as having helped broker it, if the Mueller investigation somehow clears him of wrongdoing, the Republicans’ position will be strengthened considerably. Then there is the question of gerrymandering. Republicans have drawn the current districts such that Democrats will have to win the overall popular vote by a substantial margin to capture 218 seats. In 2012, according to David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report, Democrats won more than 50 percent of total House votes but only 46 percent of the seats. This spring, Wasserman reckoned that the Democrats would need to win the popular vote by 7 percentage points overall. He could be on the low end. The Brennan Center issued a report in March putting that figure at 11 points.

That’s a tall order. It may be almost impossible. On the other hand, though, Democrats have won special election after special election this year, and even the ones they’ve lost have been far closer than the results usually are. Every sign that doesn’t have to do with gerrymandering points to a blowout. In mid-April, an NBC–Wall Street Journal poll found 66 percent of Democrats saying they were enthusiastic about voting this fall compared to just 49 percent of Republicans. That is an exact mirror image of an NBC-Journal poll from 2010, when the Republicans rolled up their 63-seat gain.

So let’s say the Democrats do it, and on January 3, 2019, some large number of Democrats is sworn in to the one-hundred-sixteenth Congress. Who will they be, and what will and should they do?

The main task is pretty simple. “A large class of 2018 that produces a Democratic majority would have as its top priority containing the damage done to American democracy by Trump and the Republican Party and setting the stage for his defeat in 2020,” said Thomas Mann, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “That means rigorous oversight, not premature impeachment, and the advancement of policies that underscore party differences on issues that matter to most Americans—economic opportunities for all, health insurance coverage, immigration, money in politics.”

The four veterans broadly agreed. They all told me that the Democrats should be aggressive on oversight across a range of areas but shouldn’t start screaming “impeach!” the day after the elections. Waxman stressed that oversight should include not just corruption-related matters like the Trump Hotel in Washington, from which the First Family continues to profit, but policy, too. “Who the tax bill is benefiting, who it’s not benefiting,” he said. “His environmental policy is the worst of any president we’ve ever had. There ought to be a very thorough set of oversight hearings on that.” So there should be, if the Democrats win, a strong push to hold the Trump administration to account on a range of fronts and some sort of pre-2020 effort to show the country what the Democrats stand for.

Beyond that: Are there any institutional reforms a new class should pursue? The Congress of the 1970s cried out for them. Today that’s not quite so pressing, given what an awful place the House used to be before the 1970s reforms, but issues certainly persist. “On my perennial wish list is a more participatory House floor,” said Sarah Binder, a senior fellow at Brookings and a professor of political science at George Washington University. “Rather than using the Speaker’s grip on the Rules Committee to foreclose amendments from rank and file in both parties, the House could benefit from a real commitment by the majority to open up access to the floor.” This, she says, could give rank and file members from both parties opportunities to introduce measures that are more bipartisan or centrist and could “counter some of the extreme centralization that polarized parties have encouraged and given rise to.”

A more controversial question is whether Nancy Pelosi might survive the arrival of a large new class, especially if a significant number of them have won in part by vowing not to vote for her as speaker, as Conor Lamb did in the March special election in Pennsylvania. “I love Nancy,” Wirth said. “Everybody does, she’s fabulous. But she’s not what’s needed right now.” Sharp agreed she’s been “extraordinary” but said that if it’s a wave election, the logic of it may well point to wholesale change at the top. “Nancy Pelosi said, ‘If it’s not me, it’s an old white male,’” said Sharp. “I think the answer to that, if I were coming in, is, ‘Bullshit. Why should I vote for any of you?’ ”

A large new Democratic class might also disrupt the “Democrats are charging to the left” narrative. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s astounding primary victory in New York City over Joe Crowley has demonstrated that someone can call herself a socialist and get elected to Congress (the general election should be a formality in that district), but there are only so many liberal congressional districts in the country; fewer than 200. So if the Democrats do get up to the 240 range, it will be with the help of plenty of moderates—as was the case in 1974. This may set up a tension that Democrats would find tough to balance. On the one hand, the 2020 presidential contenders are going to start to emerge. Most of them are going to be pushing the party left on nearly every front. On the other hand, a good 30 or 40 House candidates, mindful of the nature of their purple-to-reddish districts and worried about getting reelected, may be resistant to that movement. This could lead to an updated version of the Hillary vs. Bernie wars of 2016, with a slightly new geographic twist—the dividing line running between purple and red districts, wherever they are, and the safely blue ones wherever they are. If the party’s presidential nominee runs well to Clinton’s left, there will be 30 or more House Democrats who will spend at least some of their time running away from that candidate’s positions.

It’s possible that opposing and beating Trump will be all they’ll need to remain unified. But politics, like life, is full of paradoxes. So it might also prove to be the case that, in terms of its size and how it got to Washington—by being against the incumbent president—the class of 2018 will be like the class of 1974, but in terms of how it influences the party’s direction it will be its opposite.