In the new David Wojnarowicz show at the Whitney, there’s a room with nothing in it. A 1992 recording of the artist reading from his memoir Close to the Knives plays to the white walls. The blinds are drawn on the room’s single window. If they weren’t, you’d be able to look out over the Hudson River Park, where derelict shipping piers once stood. Wojnarowicz cruised those piers, wrote about them, painted on their ruins. There’s no sign of them now.

Wojnarowicz’s New York is gone, and so is he; he died of AIDS in 1992, at age 37. The nature of his death is the thing people are most likely to know about him, apart from the facts that he had a beautiful face and a terrible childhood, and hustled as a teenager in Times Square. The most famous images he made are about homophobia and AIDS. The poster for the 1989 Rosa von Praunheim film Silence = Death, which shows him with his lips sewn shut, comes directly from his 1986-7 art film Fire In My Belly. The 1990 work Untitled (One Day This Kid…) frames a picture of Wojnarowicz as a child with a series of declarations: “One day politicians will enact legislation against this kid....Doctors will pronounce this kid curable as if his brain were a virus....All this will begin to happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.” These works function as advocacy as much as art.

Because the best-known pieces in Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre draw from his direct experience, the curators of the museum’s retrospective, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night, were stuck in a bind: To what extent would the show commemorate the man, and to what extent would it focus on the art? They seem to have gone with “as much as possible of both.” The nine rooms hold paintings, prints, collages, photographs, and journals, as well as films and recorded music, drawn from the last decade and a half before his death—the only thing the exhibition stops short of including, it seems, are the walls of the East Village building on which Wojnarowicz stenciled the image of a burning house.

This maximalist approach is thrilling but can feel somewhat incoherent, an effect not least of the sheer breadth of media Wojnarowicz employed. Among his most affecting projects is a series of black-and-white portraits he took of himself and his friends, each in delicate chiaroscuro. In his 1980 study of Iolo Carew, fingers flutter over skin. The pictures are poetic, the kind of thing that you want to see in isolation so that you can swoon over them in peace. The most famous are a trio he took of Peter Hujar, his long-time friend and sometime lover, just after Hujar’s death. One shows the man’s Christlike, absent face. The next, his hand. The next, his feet, toes bunched together. What I felt looking at these photographs must be what devout Catholics feel when they look at images of suffering saints.

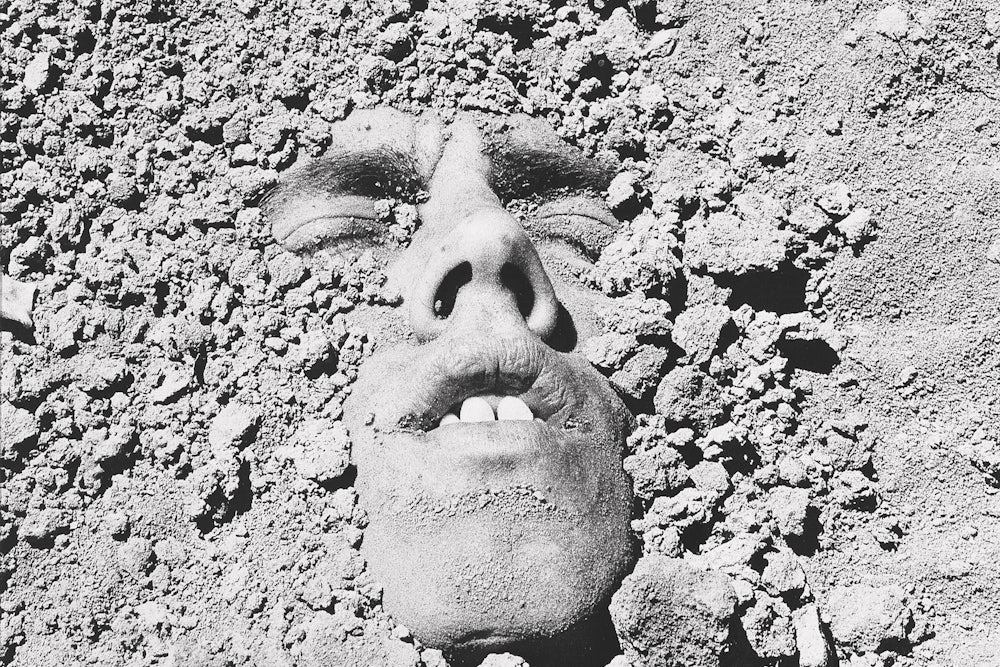

In another black-and-white series, which he called Arthur Rimbaud in New York, Wojnarowicz dressed friends in a mask of the French poet’s face and photographed them in places that had been important in his own life (Times Square, Coney Island, the piers). The prints are quite small and modest. In an adjoining room, meanwhile, hang his stencil works—big, bright collages mixing Kraft posters and maps and images of sex. Playing in the background is a recording of Wojnarowicz’s tinny band 3 Teens Kill 4. The contrast between the rich Rimbaud material and the jittery mood of the stencil room is jolting.

Hujar proves to be the link between the soulful photographs and the more antic colorful work. A series of works with the words “Peter Hujar dreaming” in their titles juxtapose outlines of that man in repose with bright acrylic-painted backgrounds and the stenciled shapes that Wojnarowicz grew so fond of. Peter Hujar Dreaming /Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian (1982) is the best of them. You can see the photographs’ elegance in the grace of the reclining form, but the color-blocking behind it adds a special force.

Perhaps the finest images, however, are Wojnarowicz’s rhetorically powerful screenprints, in which he joins text and image to speak truths about AIDS, as in the 1990s work Untitled (ACT UP). The work consists of two prints. The first layers a breathless rush of words in green lettering over black-and-white images of floating bodies: “I was told I have ARC recently and this was after watching seven friends die in the last two years slow vicious unnecessary deaths because fags and dykes and drug addicts are expendable in this country ‘If you want to stop AIDS shoot the queers’ says the ex-governor of texas,” it reads. (ARC was a common way of referring to HIV-positive status at the time.) The other layers a stock-market printout, in green, over a bull’s-eye in the shape of the United States. Like Untitled (One Day This Kid...), the prints advocate for the destigmatization of HIV/AIDS. They are elegant images that are optimized for mass communication. They are designed to be seen out in the world, not hidden in a gallery.

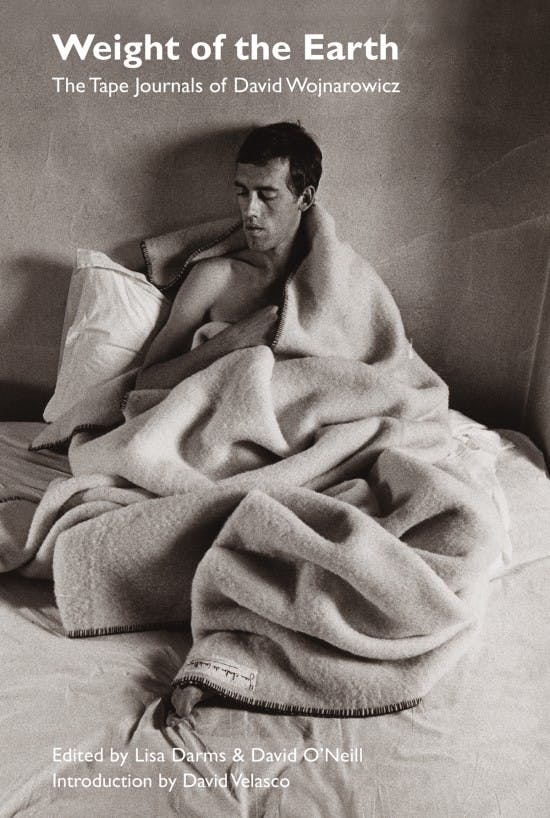

This summer, Semiotext(e) published transcripts of Wojnarowicz’s audiotape journals, mostly recorded between 1987 and 1989, which until now have languished in NYU’s Fales collection. Wojnarowicz was a fine writer, as can be seen in his memoirs Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991) and Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992), and in his many catalogue essays and diaries. Close to the Knives opens with Wojnarowicz’s recollections of street life in Times Square, memories of hallucinating from hunger and marketing his body to pedophiles. Elsewhere, he writes of those piers on the west side, “night in a room full of strangers, the maze of hallways wandered as in films.” This new volume, titled Weight of the Earth, shows a different side of him. It is a record of the present rather than a recreation of the past—he is preoccupied with dreams, little romantic dramas, what he feels like eating for dinner, his health.

Wojnarowicz used the audio diary to record his thoughts as they happened, and the transcripts have an off-the-cuff immediacy that is hard to find in the Whitney show. He describes a shift he worked at the Peppermint Lounge, muses on a fling he’s in the middle of—“I think of the silliest things,” he interrupts himself to say. He knows he has “ARC,” the term in currency then to describe being HIV positive, but he isn’t interested in memorializing himself in some grand way. He made masks of Rimbaud, he didn’t want to be Rimbaud. “I don’t think about death very much,” he says, “because it won’t let itself be thought of.”

Yet the presence of death inevitably made his days more vivid. In one journal entry, made while on a road trip, Wojnarowicz describes “a mortality hallucination,” a moment in which he realizes “just how alive I am and also the impermanence of it”:

Yeah, I’m alive, but, you know, I could be dead another year from now or two years from now. And I won’t see this road, and I won’t see the sunlight, and I won’t see these fast trucks driving by—the long, long road up ahead of me, and a long, long road in the rearview mirror. And time just moves so slow, and time moves so fast—and then time stands still for some, and time just speeds up for others. For me, at this moment, I’m in quite a dislocation of time, from both outside of time and inside of time at the same time. And all the world looks pretty great.

The joy Wojnarowicz took in his work—the joy of bright color and the sheer beauty of being a living body—resists museumification. All those strange paintings, the tender photographs, the audio diaries, even the silly band—everything exists passionately in the present tense. He cared about how the light reflected off the trucks, not about understanding death. And so this museum’s attempt to make for him a legacy, to delve inside the man as political symbol and to unite that identity with his playful art, just doesn’t quite work. If death won’t let itself be thought of, it certainly won’t let itself be curated.

New York will never be a neutral place in which to look back on the history of New York, or at the people who have lived and worked here. It’s a place with a truly abnormal way of treating memory. As communities engaged in frantic remembrance of all the people who died of AIDS—whole groups of friends just deleted by its breathtakingly rapid spread—their mourning got digested by institutions into themes, grad school classes, and nostalgia, even as people throughout the city are still living with the illness. Wojnarowicz’s activism defined how we see his work. How could it have been otherwise? He lived and worked during an epidemic that eventually took his body, too. We still need symbols of resistance against misinformation and stigma, because we are still defending the rights of queer people to medical access, to lives lived free of abuse, to visibility amid normative culture. But a symbol is not the same thing as an artist. The works on display at the Whitney show that although Wojnarowicz has become a very specific icon, his art had many strands. Wojnarowicz sewed his lips shut to protest the silence that helps HIV/AIDS flourish, not because he wanted to make himself mute. Wojnarowicz the symbol sits uneasily beside the flowering multiplicity of his work. This show is a rare chance to see the many David Wojnarowiczes at once, beside one another; just don’t mistake the poster for the man.