In August of last

year, a man named Andrew Dodson took part in the Unite the Right Rally in

Charlottesville, Virginia. There are videos of him marching toward Emancipation

Park, along with hundreds of neo-Nazis, fascists, skinheads, alt-righters, white

supremacists, neo-Confederates, and garden-variety racists. I remember seeing

Dodson in Charlottesville, looking out of place in a sea of khakis and army boots, of black

uniforms and lacrosse helmets and homespun shields. He wore a red Revolutionary

War–style tricorne hat and a white linen suit that made his bushy red beard all

the more conspicuous.

Initially, amateur investigators wrongly identified Dodson as Kyle Quinn, an engineer in Arkansas who was quickly subjected to a torrent of online abuse. Then, a week after the Unite the Right rally, the Tumblr account Yes, You’re Racist identified Dodson, or doxxed him. The account published a picture of Dodson taken during the march, identifying him by name and listing a place of employment and the town where he lived. Logan Smith, who operates the Twitter account @YesYoureRacist, exposed the identity of several other participants of the rally and sent out a call to identify Dodson. His aim was to communicate that attending white supremacist marches came at a price. “If these people are so proud to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with white supremacists and neo-Nazis, then I think that their communities need to know who these people are,” Smith told MSNBC.*

After the doxx, Dodson was reportedly let go from his job in Massachusetts. Then, on March 9, he died. For more than two months, his death went largely unnoticed, with the exception of a March 14 obituary in a local paper in South Carolina, where he was born.

In May, however, white supremacists began claiming that Dodson was a martyr to their cause. Richard Spencer called his death an act of war. RedIce TV, a Swedish far-right outlet, created a hagiographic video in Dodson’s memory, replete with throbbing hearts, dramatic black-and-white images, and somber music. The mourners asserted that Dodson had killed himself following a massive campaign of harassment, designed to isolate him from his family, friends, and employer. In a video posted to Reddit, Dodson can be seen insisting that, after the doxx, his opponents were “trying to make me lose my job, trying to threaten my family.” The actual extent of the harassment is unclear, and there is no evidence so far that his death was a suicide. (His family declined to comment for this article, as did his coroner and funeral home.) But that hardly mattered to the alt-right: The point they wanted to make, facts notwithstanding, was that Dodson’s doxxing was proof that there was no low to which the left, in its rabid thirst for blood, would not stoop.

As Laura Loomer, a former activist with the conservative group Project Veritas, famous for its misleading “sting” operations against liberal organizations like Planned Parenthood, tweeted, “Left wing insanity is killing people. This is so SAD!” In their outrage, the far right conveniently left out their own long history of doxxing. Chat logs obtained by the alternative media collective Unicorn Riot showed a concerted effort by members of the far right to release identities not only of antifa members and other left-wing activists, but also of journalists, “Marxist professors,” and “liberal teachers.”

For the leftists combating the far right—a fight that has occasionally exploded into spectacular violence in places like Charlottesville, but has largely taken place on the internet—Dodson’s death, if it could be linked to his doxxing, was proof that the strategy worked. “If he did commit suicide after being doxxed, my attitude is: Thank you,” Daryle Lamont Jenkins told me. Jenkins is an anti-fascist activist, and his website, the One People’s Project, has been doxxing members of the far right for years. (Its slogan is “hate has consequences.”) Doxxing, public shaming, loss of employment, even death—all are the price you should be prepared to pay for racist behavior, according to Jenkins.

He told me that he didn’t care about the effect any harassment may have had on Dodson. He also brought up Heather Heyer, who was killed by a white supremacist in Charlottesville: “He most certainly didn’t care for Heather Heyer, so why should we care for him?”

Jenkins’s position is extreme, and would seem to be evidence of the far right’s argument that the left has gone beyond all decency. The use of radical tactics like doxxing, furthermore, has serious implications in an era when people are willing to go to great lengths to combat the threats that emanate from the White House and the worst of its supporters. Perhaps there are few outside the racist right who would mourn the death of Andrew Dodson, and fewer still who would argue that he deserved anonymous cover to spread racial hatred. Still, is there any resistance tactic that is out of bounds when it comes to fighting Nazi trolls? Did Andrew Dodson’s supporters, for all their hypocrisy, have a point? Or were they deliberately conflating two very different things, in an attempt to create a false moral equivalence between vicious online harassment and a powerful tool in the fight against violent racism?

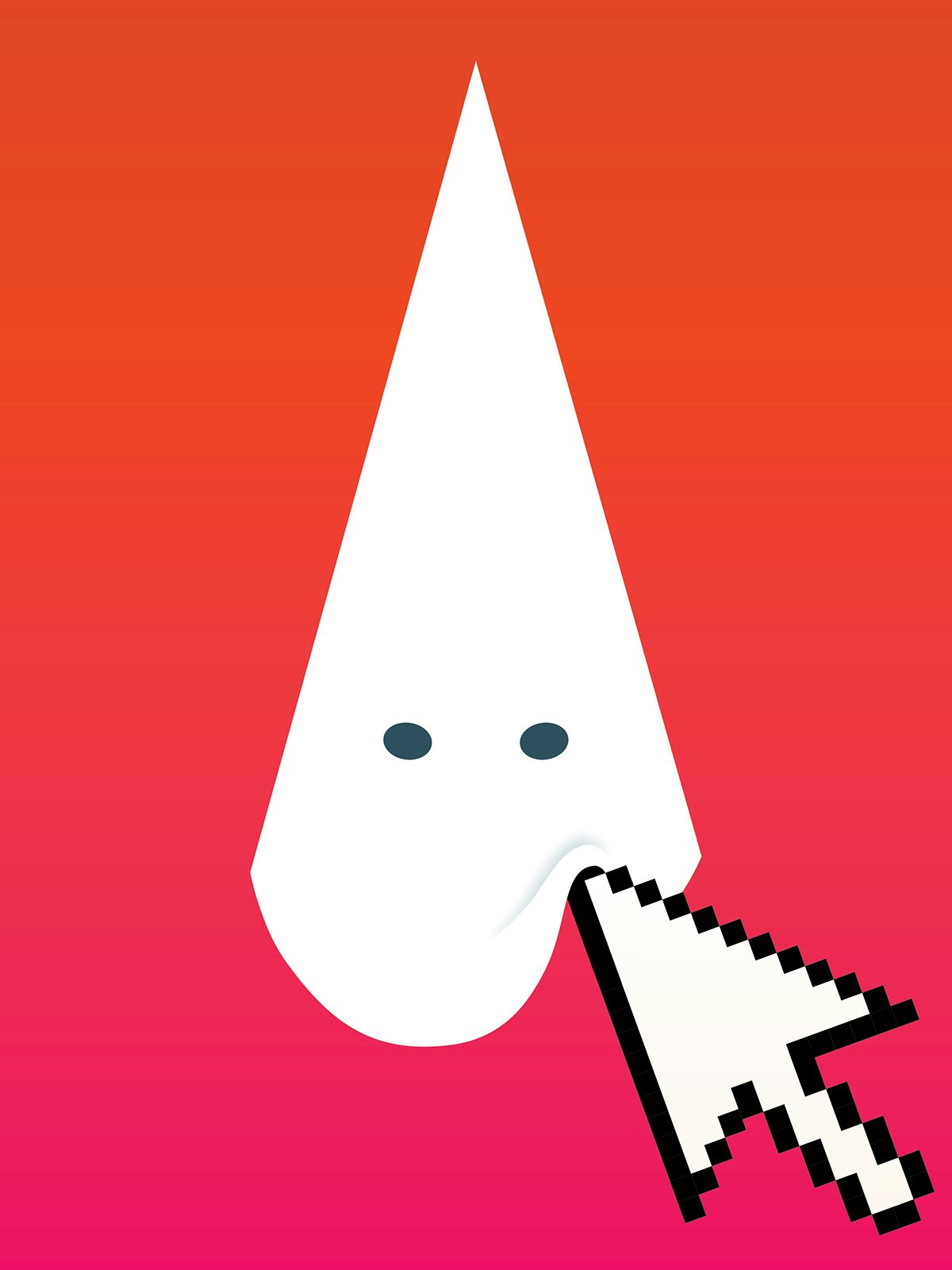

The tactic of exposing people’s identities to fight racism has a precedent in the U.S. The governor of Louisiana, John Parker, suggested in a speech in 1923 that “the light of publicity” should be turned on the Ku Klux Klan: “Its members cannot stand it. Reputable businessmen, bankers, lawyers, and others numbered among its members will not continue in its fold. They cannot afford it.” Later, during the Civil Rights era, several newspapers, aided by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, printed names and ranks of local Klansmen.

But the impact was limited to local communities, where the identities of Klansmen were often common knowledge anyway. As a political tool, the publishing of private information became more potent in the 1980s and 1990s, when it was used by right-wing Christian conservatives against abortion providers. And it was thanks to the internet that doxxing, as it is now known, became widespread and devastatingly effective.

I first met Jenkins outside the CPAC convention in Washington, D.C., in 2015, where I was reporting on the nascent far-right groups that were mingling with the GOP establishment with new intimacy. Jenkins had been warning people about the far right for more than a decade. In the 1990s he was a young activist trying to figure out how to fight the forces of white supremacy in America. He wanted to expose the racists to the world, to shame them into submission. The problem was that, as an African-American, his options for doing so were limited. He couldn’t very well go undercover and report on them.

“I had the idea of publishing names and addresses after I saw anti-abortion activists doing it to abortion providers,” Jenkins told me. During the 1980s and 1990s anti-abortion activists routinely distributed the personal information of abortion providers, many of whom became targets of threats and violence. In 1997, anti-abortion activist Otis O’Neal “Neal” Horsley published the infamous “Nuremberg Files” website, a list of almost 200 active abortion providers, complete with photos, home addresses, and phone numbers. The site celebrated any act of violence against the providers and contained thinly veiled encouragements to its readers to take matters into their own hands.

In 1995, Planned Parenthood sued Horsley along with the American Coalition of Life Activists, claiming that “wanted”-style posters of abortion doctors presented a threat to them. Planned Parenthood won the case but lost on appeal, when a federal court ruled that the First Amendment protected the Nuremberg Files.** A later appeal eventually overturned that verdict, but at that point Jenkins had had an epiphany: “When abortion providers took these people to court and lost, I said, ‘OK, this is another tool we could use.’” The lesson that he took from these early anti-abortion doxxes wasn’t that releasing private information could get people killed, but rather that you could do it and get away with it. “We didn’t see it as a weapon,” he said. “We never used it as a threat. We wanted to be open about what we saw and this allowed us to be open.”

Until relatively recently, online doxxing was contained to the trenches of various culture wars in remote regions of the web. But as social media became the dominant force of life online, these disputes were opened to a wider audience. In 2011, the hacker collective Anonymous, which was then relatively unknown, released the names and addresses of several police officers who used excessive force against Occupy demonstrators in New York City. It was, in the eyes of the activists at least, a democratization of force. They were not powerless anymore.

And then came the trolls. In 2014, on the message board 4chan, users conjured a spurious set of accusations regarding computer game developer Zoe Quinn. As the made-up scandal gathered steam, Quinn was subjected to an orchestrated harassment campaign that included not only a multitude of rape and death threats, but also the publishing of her private information. Doxxing could no longer be considered merely a tool the righteous could use to expose and shame evildoers; it was available to anyone and could be used on anyone.

Doxxing, even in the most extreme cases, is fraught with ethical complications. On the one hand, those who choose to publicly take part in extreme political action accept that their identities will be public, too. It is the price of doing business, and most on the fringe right understand that. When Matthew Heimbach, the disgraced former leader of the Traditionalist Worker Party, one of the more notorious neo-Nazi groups to gain prominence in the 2016 election, slept with a loaded shotgun next to his bed, it was because having his address known by his political adversaries was a risk he had been willing to take. Heimbach was a high-profile leader in the white nationalist movement, and he and his wife had accepted the possible repercussions.

On the other hand, doxxing can be an ugly and indiscriminate weapon, even when used in the fight against white supremacy. Katherine Weiss, a low-level member of Heimbach’s group, was once doxxed. She showed me numerous texts and emails of rape and death threats. Weiss’s white supremacist views were abhorrent, but is a threat of being “raped to death” justice? The trolls and racists of the far right regularly threaten female journalists and activists with sexual violence and death—which makes it all the more sobering to see the same threats going in the other direction.

Is doxxing excusable when used against the right targets? Do the ends ever justify the means? In a ProPublica article published in the aftermath of Charlottesville, Danielle Citron, law professor at the University of Maryland, warned of the dangers of the practice. “I don’t care if it’s neo-Nazis or antifa,” she told ProPublica. “This is a very bad strategy leading to a downward spiral of depravity. It provides a permission structure to go outside the law and punish each other.”

To an extent, Jenkins agrees. “I think right now things are becoming a little dicey,” he said. “More aggressive. Nobody wants to see anybody hurt.” But he places the blame at the feet of those in power, not the doxxers: “The political process is such that you don’t really see solutions to problems. People are at a loss as to how to change society and they are lashing out.”

In the super-heated environment of the Trump era, the pool of potential doxxing targets has grown. A few weeks ago, as Donald Trump’s policy of zero tolerance on the border between the U.S. and Mexico forcibly separated thousands of children from their parents, calls went out to doxx the employees of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE). Sam Lavigne, an artist who works with data and surveillance in New York, used software to scrape the LinkedIn profiles of nearly 1,600 ICE employees. “No one really seems willing to take responsibility for what’s happening,” he told Vice. “I wanted to learn more about the individuals on the ground who are perpetrating the crisis.”

An employee of the Department of Homeland Security recently found a burnt and decapitated animal carcass on their doorstep. Jordan Peterson, the controversial conservative professor, doxxed two of his own students for organizing a protest against a right-wing free speech rally. Employees and associates of Planned Parenthood get doxxed on an almost daily basis.

Journalists are targets, too. In May, HuffPost reporter Luke O’Brien wrote a story that revealed the identity of noted racist blogger Amy Mekelburg. The harassment started even before the story was published. Under her Twitter handle @amymek, Mekelburg accused O’Brien of stalking her, using the reporter’s requests for comment as evidence that he was harassing her. Almost immediately, O’Brien and several people around the country who shared his name were set on by an army of Mekelburg’s defenders. They either did not know or care that his only crimes had been rigorous journalism and giving a very public political figure the opportunity to comment on a story about her. Violent threats started pouring in through Twitter, emails, text messages, and phone calls. Soon personal information about O’Brien’s family was published online. O’Brien spent 20-hour days gathering evidence of threats, which Twitter officials did little to combat.

Another person named Luke O’Brien, who works as a freelance defense analyst, received dozens of threats over Twitter and email. He told me that he had defended the other O’Brien—until people started showing up outside the house where he lives with his wife and child. “It was enough to poison the well and make me reconsider how I dealt with them,” he told me. “Is it really worth the safety of my family to say what I believe, which is that these people are horrible?”

Doxxing journalists is nothing new. There have been many instances of a reporter’s personal information being released, and most female journalists are well acquainted with the realities of online harassment. Over the course of tormenting O’Brien, white supremacist trolls spawned a new meme. Pictures of bricks turned up in the inboxes of journalists all over the country. On them were the words “Day of the Brick,” a reference to “Day of the Rope,” a plot point in neo-Nazi Bible The Turner Diaries, where the heroes of the book spend a day hanging lawyers, teachers, journalists, and other “traitors.” The fantasy of hanging journalists was replaced with the fantasy of smashing them with bricks. By doxxing O’Brien, the trolls meant to threaten all members of his profession.

“They don’t care who they go after, that’s part of the strategy,” O’Brien told me. “They go after everyone else until they know they have the right person.”

Few outside the outraged feedback loops of the far right would agree with O’Brien’s attackers that the aims and practices of journalism and those of doxxing are equivalent. A journalist provided, in this case, a public service by identifying dangerous white supremacists, whereas the doxxers who revealed his family’s personal information were trying to intimidate someone they considered an ideological opponent with an omnipresent threat of violence. But the conflation of genuine reporting with doxxing points to a foundational challenge in considering the issue.

“One of the problems is that not only our opinion about when doxxing is right and wrong, but also about what constitutes doxxing, often change with who is doing it,” said Steve Holmes, an assistant professor in the department of English at George Mason University who has written extensively on the ethics of doxxing. “When you support the motives behind a given doxx, it is easy to go along with it as a justifiable act.”

The far right considers the practice of releasing personal information about anti-fascist activists a useful weapon. But when a journalist like O’Brien exposes one of their own, they consider the release of personal information an inexcusable violation of privacy. Similarly, those on the left are affronted by threats against anti-fascist activists, while supporting the doxxing of ICE employees.

The best way of looking at it, according to Holmes, is on a case-by-case basis; broad conclusions should be avoided. “Perhaps we need a taxonomy of the different forms of doxxing,” he suggested. “Doxxing can be a political threat, the revenge of a jilted ex, the exposure of toxic ideologies, and it can be the act of a whistleblower. We need a way to differentiate.”

Naming white supremacists would seem to fall clearly into a category of exposing a toxic ideology. O’Brien told me that, while he was torn on doxxing as a general practice, he saw its value in exposing violent racists. “There’s a logic to it coming from antifa,” he said. “If you have a crypto-racist and fascist living next door to you, you’d probably want to know about it.” For Daryle Lamont Jenkins, a white supremacist who is active politically has forgone the right to privacy. “Until you show me a better way to defeat them, then shining a light on these people is the best thing we got,” he argued.

Much like those who go after the worker bees of ICE, Jenkins targets the lower-level Nazis of the white supremacist movement. The leaders, he said, are public anyway. It is the foot soldiers that he believes can be scared off by the prospect of being outed. There is anecdotal evidence that supports his belief. The spotlight that was trained on the far right after Charlottesville not only caused members to leave the movement, but also led to entire groups shuttering.

“Doxxing is a major hindrance to the far right, as it is one of the main stumbling blocks to real-world organization,” said George Hawley, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Alabama who has studied the far right in America. As he sees it, the threat of exposure has taken a significant toll on the white nationalist movement. “The social consequences of being associated with one of these groups can be quite high,” he said, “and for that reason few people are willing to do more than post anonymously on the internet.”

Jenkins believes the recent successes of the doxxing campaign can be attributed to the changing nature of the far right. The current crop of white supremacists, known in the movement as “white nationalism 2.0,” are a different crowd than the 1.0 gang. “These are people who want to be in society,” he said. “They want to be doctors and politicians and police officers, and they can’t do that if they get publicly known as a Nazis. The 1.0 crowd didn’t care. They weren’t worried about getting into mainstream society.”

The 2.0 nationalists have much more to lose, but since they are part of the mainstream they are also, according to Jenkins, far more dangerous. This presents its own challenges for the doxxers of the anti-fascist movement. You can only get doxxed once; after that there is not much left to do to a person. “Doxxing has less of an effect the more committed a white supremacist you are, because you’re more likely to have already revealed your beliefs or be less troubled in having them revealed to the world,” said Mark Pitcavage, senior researcher at the Center on Extremism at the Anti-Defamation League. “It is most effective against those white supremacists, often relatively new, who worry about leaving the closet.”

Oren Segal, the director of the Center on Extremism, added that doxxing has led racist agitators to hide themselves better. “It is common to see younger white supremacists covering their faces in their propaganda these days,” he told me. “Even flash demonstrations, which are primarily a response to antifa, enable white supremacists to have greater control of the presentation of their images.”

Still,

the point of doxxing is to spread fear. Just because one doxxed nationalist has

nothing left to lose, it could still affect the choices of those who remain

anonymous. “Doxxing extends beyond hurting a particular individual,” Hawley said.

“The goal is to make an example out of someone, to show others what can happen

if they sign up with the radical right.”

In this respect doxxing, for all its complications, has undeniable upsides. Pointing out that people on both the far left and the far right utilize doxxing creates a false equivalency, rooted in the notion, made famous by Donald Trump after Charlottesville, that “there are good people on both sides.” The threats of violence leveled at female, Jewish, and African-American journalists and activists are not matched by anything experienced by white people on the fringe right. The orchestrated efforts of that cohort to harass and threaten those with whom they disagree or simply dislike are unrivaled by anyone else, as is their blanket encouragement of violence against reporters.

But there is political expediency in lumping the two sides together as equal combatants. The disruptive protests by the Black Bloc faction of antifa during Trump’s inauguration, their brawls with fascists on the streets of many American cities, and their efforts to shut down speaking engagements of far-right speakers, have led conservatives in Congress to realize that there is political hay to be made. To that end, Rep. Dan Donovan of New York came up with HR 6054, also known as the “Unmasking Antifa Act.” The law aims to target anyone who “injures, oppresses, threatens, or intimidates” those exercising a constitutional right, but is widely seen as an attempt to cast antifa and other left-wing protesters as a threat to public safety, ignoring the fact that far-right activists have a far bloodier track record, not just in recent times, but also throughout the last century. In fact, 18 states already have anti-mask laws, enacted in response to KKK violence during the Civil Rights era.

The bill, designed to equate the far right and the far left, is of a piece with far right joining Andrew Dodson’s death to their cause. It is a tool used to validate the assertion that leftists are a violent mob out for blood, that their version of rough justice is completely depraved. These are polarized times, but justice is not simply in the eye of the beholder—at least not yet.

*An earlier version of this article implied that Logan Smith ran the Tumblr account Yes, You’re Racist. He denies any involvement in the account, despite the fact that the Tumblr is identical in several respects to the Twitter account @YesYoureRacist.

**An earlier version of this article stated that Planned Parenthood brought a case in 1995 against Neal Horsley based on the Nuremberg Files. In fact, it was based on “wanted”-style posters of abortion doctors, though the case ultimately ruled on the legality of the Nuremberg Files.