If

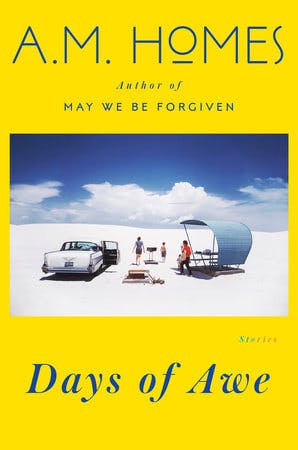

the brief half-life of literary celebrity these days gets you down, consider A. M. Homes. Days of

Awe, recently published, is Homes’s third story collection after The Safety of Objects (1990) and Things You Should Know (2002). Since

1989 she has also published seven novels and a rich array of essays, mostly on

art. Nineteen years ago Gary

Krist called her novel Music for

Torching, about a couple who burn down their own house, “nasty and willfully grotesque.” Three

years earlier, her novel The End of Alice

left a bruise on literary culture so indelible that it might as well be a

tattoo. That book was largely narrated by a pedophile in correspondence with a

young girl. Homes is 57 years old. She was a scriptwriter for

the second season of The

L Word. Hers is a well-rounded career of satisfying, weird ambition.

Days of Awe is different from most of her other books, because it is not, for want of a better phrase, as horrifying. Across twelve stories, Homes uses her familiar approach of seeing American families from an oblique angle. Magic interferes and reveals aspects of their lives that were hitherto hidden. In “A Prize for Every Player,” a family that has made a game out of doing the grocery shopping finds the stakes of play elevated when the father is nominated to the presidency by bystanders in the store. In “Omega Point,” a family’s overlooked grandmother turns out to the blessed heir to Lue Gim Gong, the Citrus Wizard who gave America the common orange. In “Your Mother Was a Fish,” a mother is a fish.

But the best of the stories contain no magic at all except the ordinary kind. In “The National Cage Bird Show,” a young Manhattanite strikes up an online friendship with a man who claims to be deployed in Afghanistan. Together they colonize a budgerigar appreciation forum, to the other users’ dismay (“Can we please stay on topic? Do any of you feed grapes to your birds?”). It is impossible for them to verify each other’s identity, or to predict whether they will meet in real life. But together they discuss death and birds, violence and mothers.

“Ordinary” families contain enough horror and evil and wonder, A. M. Homes appears to conclude in this collection. There is so much to say that her characters seem to burst out of the narratives that hold them. The most explicit expression of this principle comes in the many conversations in Days of Awe that play out through ventriloquy.

In “All is Good Except for the Rain,” two old friends, Genevieve and Sarah, replay the divorce between Sarah and her husband. “‘Did you tell the kids yet?’ Genevieve says.” Sarah, across the table, replies, “‘“No.”’” Genevieve again: “‘“Why not?”’” That’s a thick layer of quotation marks, because I am quoting the story that quotes characters quoting other characters, who are offstage. Sarah’s husband left her in a flurry of complaints about her tits, which have become too hard, in his opinion. Sarah was “left without words,” she says, when he did this. The friends convert the passive experience of being struck dumb into a great complex heap of words that they own. They act out the marriage crisis in a play, collaborating to create or affirm the reality that they share.

Shared language begets control over reality, which can be very terrible. In the collection’s title story, a character called “Transgressive Novelist” (a cipher for Homes herself?) attends a conference on “Genocide(S).” There, she meets an old friend—“War Correspondent”—to whom she is inextricably attracted, even though she has a partner back home. These two writers, the man and the woman, are both drawn over and over again to the genocide. They are professional witnesses. She writes fiction about the impact of the Holocaust on subsequent generations. He takes his notepad and camera to the places where children are blown up.

Together, the pair contemplate their own motivations. But in the story’s finest moments, Transgressive Novelist and War Correspondent speak to each other, like Sarah and Genevieve, through voices that are sort of their own but not quite. “Ah, Erike, I wanted a weekend like when we were young and used to play hide-and-seek in the pickle barrel, before we had so much responsibility…,” she says, becoming a put-upon Jewish mother of generations past.

“Remind me, how many kinder do we have?”

“Ten,” he says.

“So many,” she says, surprised. “And I gave birth to them all?”

“Yes,” he says. “The last three it was less like a birth and more like they just arrived in time for dinner.”

They are cute together, funny. Both writers are pulled, perhaps dragged, into obliterative violence. But by assuming the identities of their grandparents, they can relinquish their roles as witnesses and instead exist. Pretending to be other people is a very good way to at last become comfortable in one’s own heritage.

Has Homes lost interest in being nasty and grotesque? Perhaps it has stopped being so fun. Or, perhaps, she has returned to the same territory, the American family, but has turned inward rather than outward. There are all sorts of funny little rooms, forgotten corners inside this old house, she seems to say in Days of Awe. No need to burn it down. In its hard-earned ease among the perils of the American home, Days of Awe feels like an authentic step forward in a career that is continuing to mature.