A two-word rallying cry on the left against President Donald Trump’s immigration policies has grown into 2,700 words of federal legislation, as Democratic lawmakers last week introduced a bill that would abolish Immigration and Customs Enforcement—the federal agency that carries out deportations and enforces many of the nation’s immigration laws—and redistribute its powers elsewhere in the federal government.

“Sadly, President Trump has so misused ICE that the agency can no longer accomplish its goals effectively,” Wisconsin Representative Mark Pocan, one of the Democrats who introduced the bill, said in a statement. “As a result, the best path forward is this legislation, which would end ICE and transfer its critical functions to other executive agencies.”

Turning that idea into policy isn’t as straightforward as the slogan suggests. There’s been ample debate about the politics of abolishing ICE: whether Democrats can unite around it, how it will play among Republicans, whom it will help or harm in the November midterm elections. But the actual policy of abolishing ICE, a $6 billion agency that employs more than 20,000 people, has received much less scrutiny. Which of the agency’s responsibilities—which extend well beyond immigration enforcement—should be eliminated entirely, and which should be preserved? And where should the latter go?

The Democrats’ bill provides few answers. Most of its text is devoted to describing ICE’s flaws: providing inadequate medical care at its facilities, turning a blind eye to sexual abuse against detainees, offering insufficient budget justifications to Congress, and more. “Any essential functions carried out by ICE that do not violate fundamental due process and human rights can be executed with greater transparency, public accountability, and adherence to domestic and international law by other federal agencies,” the bill surmises.

If signed into law, the bill would set a one-year window before ICE is shut down, while also establishing a commission to undertake a 90-day review that would identify ICE’s essential responsibilities and the agencies that could take over those roles. A second act of Congress would then be needed to establish where its former powers should go. Commission members would also be charged with accounting for any constitutional infringements and abuses of power committed by ICE agents and officials during its existence.

“This legislation would establish a commission to look at transitioning essential ICE functions to a new agency that would have accountability, transparency and oversight built in from its inception,” Washington Representative Pramila Jayapal, another Democrat who introduced the bill, said in a statement. “It’s time to change the system to one that is accountable, efficient, humane, and transparent.”

Sean McElwee, a Data for Progress co-founder who popularized the idea of abolishing ICE last year, told me that he considers the bill a “good first start” toward dismantling the agency. But he acknowledged that there are still open questions about what exactly should take ICE’s place, if anything. “At this point, there isn’t alignment within the immigrant-rights community and the groups that have been pushing to abolish ICE as to what a concrete next step would be,” he said. “What the bill is meant to do, I think it does quite effectively. The detailed findings that make up the majority of the text are quite powerful.”

McElwee indicated that liberal and left-leaning think tanks have a role to play in fleshing out what should happen next. “The D.C. policy apparatus isn’t serving what I view its function should be, which is to take the demands that activists and Democratic voters have, and try to find a way to turn those into policy proposals,” he told me. McElwee said he expected that there would be “a fully-limbed vision of this” in the coming months, “and then I think we’ll have an important back-and-forth as to what exactly that will look like.”

Here’s a glimpse of that coming debate.

ICE’s origin story begins with 9/11. In response to the attacks, Congress established the Department of Homeland Security in 2003 by restructuring almost two dozen agencies from across the federal government. Three DHS agencies emerged from the dissolution of the Immigration and Naturalization Service: Citizenship and Immigration Services, which handles naturalization and other lawful immigration; Customs and Border Protection, which focuses on border enforcement of immigration and customs laws; and ICE, which enforces them everywhere else.*

Calls to rethink ICE’s existence first began percolating on social media last year as Trump’s hardline immigration policies, notably a sharp increase in deportations from the interior U.S., began to take shape. By this spring, immigration-rights activists began to lay out the full case against the agency’s existence. “The call to abolish ICE is, above all, a demand for the Democratic Party to begin seriously resisting an unbridled white-supremacist surveillance state that it had a hand in creating,” McElwee explained in The Nation in April. He called on progressives to “demand that deportation be taken not as the norm but rather as a disturbing indicator of authoritarianism.”

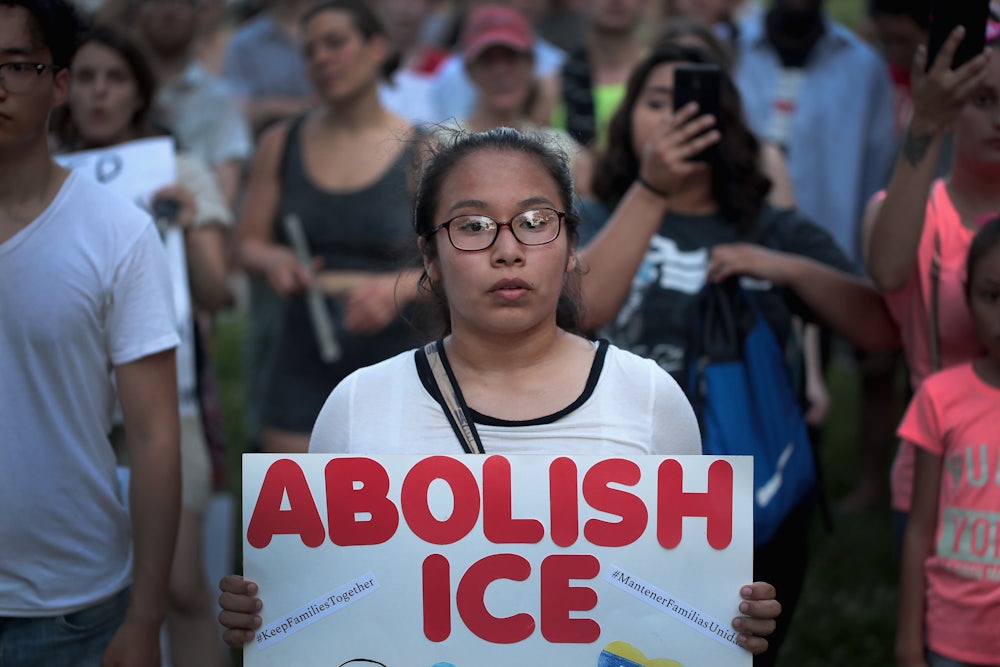

But it took two events in June to put #AbolishICE on the national radar. The Trump administration’s family-separation policy snowballed into a major political crisis for the White House, one in which ICE played a highly visible role. Images of children detained in chain-link cages drew genuine bipartisan outrage that eventually forced Trump to back down and start reunifying some children with their parents. ICE’s abolition quickly found a more receptive audience among Democratic lawmakers in the weeks that followed.

Then, in an election on June 26, congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pulled off an upset against Joe Crowley, a longtime Democratic lawmaker from New York and a member of the party’s House leadership. Ocasio-Cortez, a 28-year-old democratic socialist, received extensive national media coverage—as did her support for abolishing ICE. A wave of high-profile Democrats, including New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, backed ICE’s abolition in the days after Ocasio-Cortez’s win.

As the idea of abolishing ICE went mainstream, so did criticism of it. The White House, perhaps trying to refocus the immigration debate after its family-separation debacle, rallied to the agency’s defense. Vice President Mike Pence visited ICE’s headquarters and vowed that the administration would “never” abolish it. In a July 1 interview, Trump said, “You get rid of ICE, you’re going to have a country that you’re going to be afraid to walk out of your house.” He also predicted that calls to abolish ICE would harm Democrats’ electoral chances in the November midterms, a possibility that some Democrats also feared. (One recent poll found that 54 percent of Americans support keeping the agency intact.)

Concerns about abolishing ICE, both as a political strategy and a practical effort, extended beyond Republicans. Eric Holder, an attorney general for President Barack Obama, described the push as a “gift to Republicans.” Jeh Johnson, who served as the secretary for homeland security under Obama, compared it to Trump’s ephemeral pledge to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. “If Americans don’t like ICE’s current enforcement polices, the public should demand a change in those policies, or a change in the leaders who promulgate those policies,” he wrote for The Washington Post.

Sarah Saldana, who served as ICE’s director from 2014 to January 2017, told me that abolishing the agency would be “nonsensical.” She took issue with the idea of approaching immigration in a piecemeal manner instead of addressing it as a whole. “This is not a question of the agency and its people, it’s a question of enforcement and how you go about it,” Saldana said. “The answer still is comprehensive immigration reform, but nobody has had to respond to the fact that it’s been years now that Congress has ignored a very important issue.”

While immigration enforcement receives the most attention, it only accounts for a third of ICE’s budget, according to Saldana. “If you do abolish ICE, you’re abolishing the United States’ representation in immigration court, you’re abolishing the extraordinary work that investigative agents do on the Homeland Security Investigations side,” she said. “That’s the half of ICE that does investigative work, which is human trafficking, child exploitation, international crime, military-arms proliferation—all of that is under ICE.”

As Saldana notes, Immigration and Customs Enforcement does more than its name suggests. (Poor nomenclature is something of a tradition for the Department of Homeland Security.) Most of ICE’s public profile comes from a single office within the agency: Enforcement and Removal Operations, or ERO, which carries out deportations and removals. Democrats have likened it to the “deportation force” that Trump promised to build on the campaign trail. ERO agents have reportedly responded to the new mandate with enthusiasm.

The second major office within the agency is Homeland Security Investigations, which resembles a traditional federal law-enforcement agency. The office was formed by the 2003 merger of the investigative divisions of the INS and the Treasury Department’s Customs Service. Its agents investigate crimes that often cross international borders: customs violations, human trafficking, child exploitation, cyber-related offenses, smuggling firearms or drugs, and more. Its broad portfolio mirrors the FBI’s role within the Justice Department, albeit at a smaller scale. While they’re structurally separate, HSI and ERO cooperate closely on day-to-day affairs.

Two other directorates round out ICE’s basic structure. One of them is devoted to management and administrative functions, a standard nuts-and-bolts component of any large government agency. The other one, the Office of the Principal Legal Advisor, is far larger than its name suggests. Its 1,100 lawyers function like a Justice Department of sorts for ICE by providing legal counsel and representation in every capacity. OPLA lawyers also represent the government’s side in deportation hearings held within the Justice Department’s immigration-court system.

Trump’s push to maximize immigration enforcement and deportations has resurfaced some tensions between the agency’s two largest offices. In a letter to Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen last month, a group of Homeland Security Investigations special agents asked for their office to be separated from Enforcement and Removal Operations, citing cultural differences in the mission and the workforce between the two principal offices. The agents also made clear, albeit politely, that ERO’s operations were undermining their ability to perform their own functions:

Furthermore, the perception of HSI’s investigative independence is unnecessarily impacted by the political nature of ERO’s civil immigration enforcement. Many jurisdictions continue to refuse to work with HSI because of a perceived linkage to the politics of civil immigration. Other jurisdictions agree to partner with HSI as long as the “ICE” name is excluded from any public facing information. HSI is constantly expending resources to explain the organizational differences to state and local partners, as well as to Congressional staff, and even within our own department—DHS.

In their letter to Nielsen, the agents framed the splitting of ERO and HSI as the logical endpoint of ICE’s evolution since its establishment in 2003 as part of the new Department of Homeland Security. In 2003, ICE absorbed the federal air marshals program from the Transportation Security Administration, another recent establishment, only to send the program back there two years later. The Federal Protective Service, which protects thousands of federal buildings across the country, also came to ICE from the General Services Administration in 2003. It was later moved elsewhere within DHS in 2009.

Saldana said that the letter reflected long-running concerns among HSI agents about their ties to immigration enforcement that predate Trump. Under the Obama administration, the office persuaded department officials to change its original name—ICE Office of Investigations—to something less overtly connected to the agency to which it belonged. Saldana noted that HSI and ERO would still work closely together if split apart. HSI’s investigations often target people who enter the country illegally or attempt to do so, and ERO is the primary office that holds and detains undocumented immigrants.

There isn’t a consensus among activists whether Homeland Security Investigations should be made independent within DHS, absorbed by another department, or divided up another way. “I think there’s a pretty diverse view within the immigrant-justice community as to how benign an institution HSI is,” McElwee said. “It’s a very sexy agency in the sense that if you’re a Democrat who doesn’t want to say abolish ICE, you can say, ‘Look, they did something about child trafficking,’ which gives the agency some political capital.”

When I asked McElwee what he would regard as success for the Abolish ICE movement, he situated it within the context of a broader anti-deportation movement, which advocates decriminalizing immigration and providing a pathway to citizenship. But he also made clear that he would like to see the Enforcement and Removal Operations office go defunct. “The job that ERO performs only really makes sense as a thing that society should be doing if you view the presence of people of color in this country as a threat,” McElwee said. “I actually think that having a big, broad discussion about what we want to be as a nation—in terms of what laws we want to enforce and behaviors we make illegal—is actually something that has to be done and isn’t thought through in a coherent way.”

ICE’s ultimate fate would hinge on how much lawmakers want to change. If ERO were shuttered, Congress could simply leave Homeland Security Investigations and the rest of ICE’s structure intact under a more suitable name. Lawmakers could also make HSI a distinct investigative agency within the Department of Homeland Security. Congress could also move the office to the Justice Department, either as a standalone agency or to be absorbed by the FBI, or to the Treasury Department, where the U.S. Customs Service once exercised similar functions.

At its broadest level, #AbolishICE isn’t just about changing DHS’ most controversial agency. It’s about changing the nation’s deadlocked immigration debate. “Everyone’s entrenched,” Saldana said, referring to Congress. “I don’t blame one side or the other for the lack of comprehensive immigration reform. Both parties are responsible, and I would hope that at some point the public gets serious enough about it to say, ‘You’re not working on a major issue in this country and we need someone who will.’”

By calling for ICE’s abolition, activists on the left are hoping to tilt that debate in their favor. “ICE is now contested,” McElwee said. “Detention beds are contested. ICE’s funding in omnibus bills is no longer a given—a thing that is seen as the thing that’s done automatically. The contesting of deportation is very valuable. We actually have some space now to question the consensus that was fundamentally a center-right consensus.” For those hoping to build a new approach to immigration after Trump, that long-term shift is more important than whatever form ICE takes next.

* This article previously misstated the agencies that emerged from the dissolution of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.