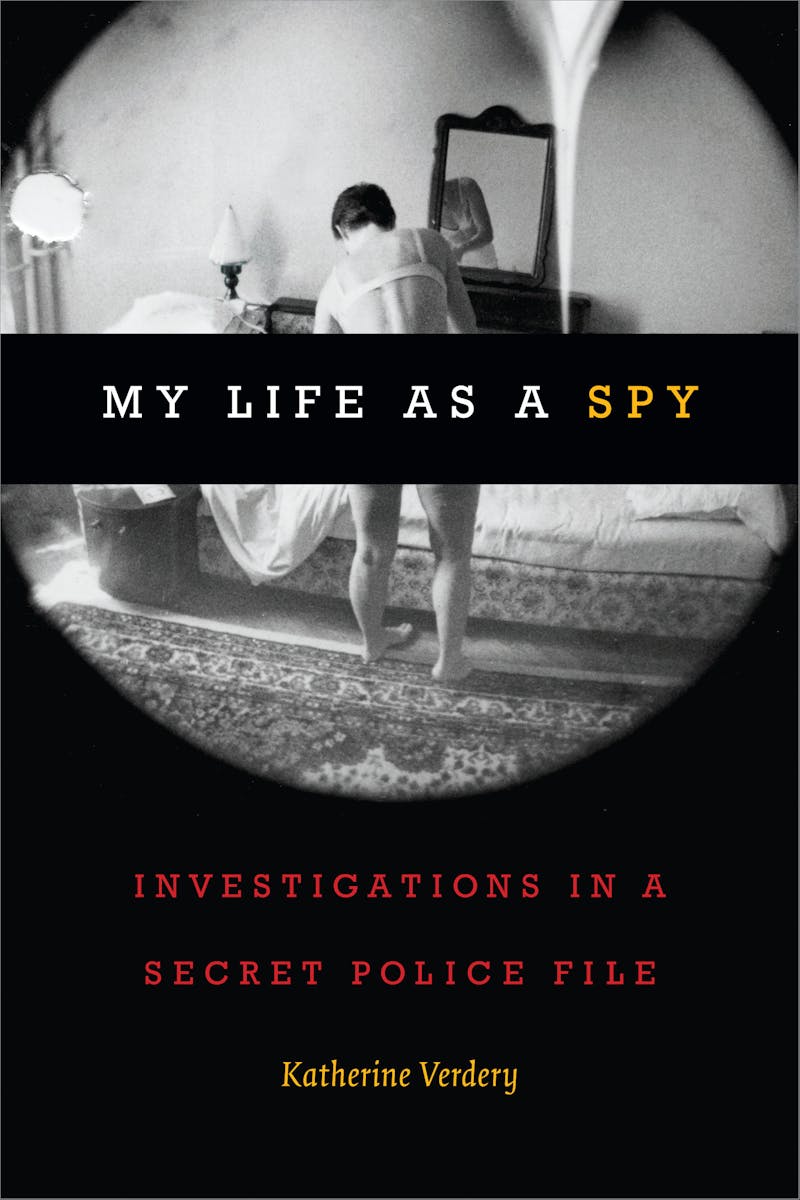

On the cover of anthropologist Katherine Verdery’s My Life as a Spy: Investigations in a Secret Police File, there is a grainy, black-and-white surveillance photograph of the author, taken during a 1986 research trip to Romania. Standing alone in her underwear, she bends down to make the bed in her hotel room, apparently oblivious to the presence of the camera placed there by the Securitate—the Romanian secret police—who had, by that point, been tracking her for over a decade.

Over the course of the 1970s and 80s, Verdery—now a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at CUNY Graduate Center specializing in Southeastern Europe—traveled regularly to Romania to conduct fieldwork, first as a graduate student and later as a tenured professor. As an American researcher in Ceausescu’s Romania, Verdery knew it was reasonable to assume that she was being watched. But when she formally requested access to her Securitate file in 2008, what she found was far more extensive than the routine monitoring of a foreign academic. Encompassing over 2700 pages of informer reports, surveillance, phone taps, intercepted correspondence, and officer notes, the file constructed an alternate version of her life in Romania, one in which her scholarly work was merely a cover for her real identity as a spy.

“There’s nothing like reading your secret police file to make you wonder who you really are,” Verdery writes in the book’s preface. Encountering the “doppelgänger” in her file—a woman who shared her name, biography, and image but was otherwise unrecognizable to her—provoked a kind of existential crisis, shattering the stability of her own self-image. She was devastated to learn that people she considered dear friends had informed on her—some offering up relatively benign reports, others quite damaging ones—and felt violated by the extent of the surveillance, which had penetrated far further than she ever suspected.

The file’s unwieldy form only compounded her sense of disorientation: Never intended to be read by anyone outside the Securitate, the pages jump abruptly between different times and places, following the agency’s inscrutable bureaucratic logic. With each visit to Romania, the aliases assigned to her proliferate—“Folclorista,” “Vanessa,” “Vera”—each of whom is presumed to be the true “Katherine Verdery.”

Verdery first arrived in Romania in 1973 as a 25-year-old Stanford PhD student with what she admits was an extremely superficial understanding of her chosen fieldwork site. The decision to go to Romania in the first place had been primarily a matter of convenience: She was interested in the idea of working on the margins of Europe and curious about life in a communist country; Romania was at that point one of the more accessible Eastern Bloc countries for foreign researchers and the language would be far easier to learn than a Slavic one.

When she returns in the 1980s, the terrain has shifted, both internationally and domestically. Her research trips during that decade take place against the backdrop of Reagan’s escalation of the Cold War, Romania’s fear of reformist movements sweeping the Soviet Bloc, and domestic economic crises that had fanned the flames of dissident movements. Now the Securitate didn’t merely watch her, but attempted to proactively influence her perception of the information she collected, instructing informers to get close to her so they might “correct” her false impressions and subtly steer her towards more favorable ones.

Though the Securitate remained convinced that her real purpose in Romania was espionage—from her first visit until the regime’s end in 1989—the imagined nature of her “spying” proves malleable, with the shifting accusations against her reflecting the government’s priorities and anxieties at a given moment. During her yearlong stay in Aurel Vlaicu, a town largely populated by employees of an important munitions factory, she is suspected of gathering military secrets for the CIA; on a subsequent trip to Cluj, the Securitate mistakes her French surname for a Hungarian one and assumes she is there to foment unrest among Transylvania’s ethnic Hungarian minority.

Later, the charge is “collecting socio-political information” that would be used to damage Romania’s reputation abroad. The Securitate’s informer network even managed to reach her back home in the United States, where they report she has been meeting with exiled Romanian dissidents. This elastic definition of spying thus encompassed more than just illicitly gathering classified information and passing it to a foreign government, as Verdery imagined it at the time. The Romanians were equally concerned with how a person would represent them to the world and how the picture she created might diverge from their official version of the truth. “She is collecting information of a sociopolitical character, which she interprets in a falsified and hostile manner,” reads a 1984 report. “Although it is not secret, [it] can be used against the interests of our country.”

Verdery hadn’t been working for the CIA, nor was she a secret Hungarian. But some of the other charges were more difficult to deny: the work of an ethnographer necessarily involves collecting “information of a socio-political character.” And in their reports, the Securitate officers assigned to her case sometimes remarked on the similarities between her fieldwork practices and their own. “They recognize me as a spy because I do some of the things they do,” Verdery writes. “When I read in the file that I ‘exploit people for informative purposes,’ can I deny that anthropologists often do just that, as Securitate officers do?” Much as the file presented her with an unsettling alter ego in the form of “Vera,” in the most extensively documented of her aliases she also found the uncanny double of her profession.

Unlike her previous academic monographs—including her 2014 book Secrets and Truth: Ethnography in the Archive of Romania’s Secret Police, a more conventionally scholarly study of the Securitate’s archives—My Life as a Spy is, as Verdery describes, a “polyphonic work,” collaging together transcripts of reports by Securitate officers and informers, excerpts from her original field notes from the ’70s and ’80s, quotations from present-day interviews with people who appear in her file, and the notes she took as she read through its pages recording her immediate responses to the material. She considers her Securitate file simultaneously an archive of her life in Romania, a quintessential Cold War document that reflects the period’s geopolitical paranoia, and a window into the Securitate’s methods.

The book’s first half takes the form of a counter-memoir in which she contrasts her experiences in Romania with the Securitate’s record of them. Rearranging the file chronologically, she recalls how she attempted, at the beginning of her career, to define herself as a professional ethnographer, while the Securitate was attempting to define her as a spy. Shy and sheltered when she arrives, with little real fieldwork experience under her belt, Verdery finds that the challenges of the environment—bureaucratic hurdles, the reticence of locals uneasy about disclosing too much to a stranger—force her to find creative ways of uncovering information, like examining headstones in the village cemetery to map out inter-familial ties.

She reflects, too, on the social and psychical stress of living—and attempting to conduct ethnographic research—in a place where pervasive surveillance is the norm. Whether she recognized it or not, the Securitate functioned as a third party to each conversation she had—in some cases literally listening, in others, simply hovering over it as a possibility, a kernel of doubt that undermined attempts to build trusting relationships.

When Verdery begins examining Securitate files, she finds another set of doppelgangers in her file alongside her own: the informers. The informer, Verdery writes, “was groomed to be complicit with his officer and duplicitous with his fellows, his self split between these personae.” An informer’s identity was only meant to be known to the Securitate officer who recruited him or her; in the file, they are given aliases, referring to themselves in their reports not in the first person, but as “Source.” Nevertheless, she is able to identify many of them tentatively based on contextual clues. In the second part of the book, she takes up a new kind of fieldwork, reaching out to the suspected informers and interviewing them about how and why they agreed to work with the Securitate.

Verdery debates whether she should name in her book the people who informed on her, ultimately deciding that they should remain anonymous. Initially, her gut reaction was to see their reports as a personal betrayal—an opinion shared by many in Romania, as in other Eastern European countries, who are quick to condemn informers as collaborators. But she realizes, after speaking with many of the friends who had informed, that that their actions can’t be understood as individual instances of malice or cowardice. They were simply attempts to navigate the world in which they lived. “I can define it either as a betrayal,” writes Verdery, or a situation in which friends were “overwhelmed by a greater exigency to which I was insignificant.”

Contrary to what she calls a “very American tendency to think largely in terms of autonomous individuals,” her relationships with her informers existed within a broader field of social ties:

clearly it is absurd for me to imagine that I will be more important to my friends than their own families, friends, and ongoing lives—relationships having much greater longevity for them than does ours, and which their reports on me protect.

Indeed, the question of harm could go both ways: Her friend “Mariana”—the only person who admitted to informing on Verdery unprompted—expresses remorse but at the same time suggests that she was a victim too, as Verdery had made her a target by soliciting her friendship.

While the security officers shaped her relationships, what impact was she having on their lives? In her final chapter, Verdery tries to track down several of the officers who appear most frequently in her file. Flipping the script, she begins following them. She looks up their addresses and phone numbers. She identifies mutual acquaintances and asks them to broker an introduction or tell her where to find them. She insinuates herself into their lives and environments, aiming to force an encounter. When one officer, “Grigorescu,” hangs up on her when she calls, she decides to simply show up at his doorstep. Her eventual meetings with the officers are more confusing than cathartic. She finds them charming, interesting, occasionally even sympathetic. “How can this be the hated Securitate?” Verdery asks. “Are they just a bunch of regular people doing their job, as Hannah Arendt said of Eichmann?”

For most of her Romanian friends, this attitude is ludicrous. But, as with the informers, Verdery argues that the question of whether to condemn or forgive individual Securists is the wrong one; more important is an understanding of how they, too, operated socially. “Securisti were not isolated from the general population but rather entangled with it,” Verdery argues. “Instead of imagining an invisible Securitate preying on a frightened populace, we should imagine a dense and varied field of relations.” Securists had friends and neighbors, too: Sometimes their relationships with informers were coercive, but other times they involved more informal, mutually beneficial exchanges. Particularly in the 1980s, a period of extreme economic austerity in Romania, people would often volunteer information to the Securists in their community without being formally recruited in hope of securing favors: for instance, access to unavailable commodities or visas to visit relatives abroad.

Created under one set of norms and opened under a new set, the role of secret police files in Eastern Europe continues to be fraught. After the collapse of the region’s communist regimes, each country passed “lustration” laws (Romania was the last, in 1999), making the files accessible to the public and in many cases identifying and sanctioning collaborators. In reframing the files as “social agents,” as she calls them in Secrets and Truths, Verdery argues that they do not so much document a particular person as produce a function—in her case, the spy, who embodied the regime’s fears about foreign enemies. The regime’s power, she concludes, ultimately resided in its ability to invade the social lives of Romanians, transforming relationships into liabilities.