On May 10, 1869, the transcontinental railroad linked America from east to west for the first time in history. It was a formidable undertaking: Over the course of six years, more than 10,000 workers built the tracks by hand in treacherous conditions. In an historic photograph marking the railroad’s completion, the men who had been involved assembled around two locomotives to celebrate the final spike. Over 80 percent of the laborers were migrants from China—and yet, not one man pictured is Chinese.

The staged photograph is an eerie artifact of the growing anti-Chinese sentiment of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, which culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Scott Act of 1888. As Beth Lew-Williams shows in her new book The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America, Chinese immigration to the United States was far from unwelcome to begin with: For U.S. politicians, missionaries, and businessmen in the 1850s, Chinese migration was a part and a parcel of American advancement in the China Trade. The influx of Chinese workers, prompted by political and economic instability following the First Opium War, provided labor for a growing U.S. economy; at the same time the movement of laborers, merchants, scholars, and missionaries between the United States and China strengthened relations between the two countries.

The ties that American expansionists embraced, however, angered white settlers in the American West. They believed Chinese migrants drove wages down, threatening the independence and self-sufficiency of white workers. They saw Chinese migrants as unassimilable because they refrained from American habits of consumption—they “did not eat red meat, buy books or nice clothes, engage in leisure,” so the stereotype went—and they didn’t appear to support dependents in the United States, instead sending their pay home to families in China. Many whites feared that the very presence of Chinese migrants would rock the foundations of the American republic. Drawing from diaries, official documents, and speeches, Lew-Williams wryly summarizes their reasoning that “while an authoritarian state” might be able to “subjugate” a minority, “a republic, it was believed, required a homogenous citizenry to survive.”

But it took a lot more than this mass of prejudice to make anti-Chinese sentiment a matter of national policy. Those policies would have far-reaching effects that extend to the present: The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Scott Act of 1888 destroyed all but pre-existing Chinese communities for nearly six decades. While it failed to actually end Chinese migration, it simultaneously barred Chinese people in the United States from naturalization and encouraged continued abuse of Chinese workers. It’s the development of this policy and its legacy that Lew-Williams has studied, tracing how white supremacist interests constructed modern notions of citizens and aliens.

Before exclusion came several attempts at limiting Chinese migration, each responding to widespread anti-Chinese sentiment among whites in the United States—99 percent of California voters, an 1879 ballot showed, were against Chinese migration. Chinese workers suffered violence and harassment, as well as organized political opposition. Leaders such as Dennis Kearney of the Workingmen’s Party of California and Daniel Cronin of the Washington Territory’s Knights of Labor exploited existing Sinophobia to position the anti-Chinese movement as “peaceful” advocacy for workers rights. Even as they claimed that they were nonviolent, they leveraged the threat of violence to pressure Congress into considering Chinese exclusion.

Split between honoring diplomacy with China and preserving order at home, Congress made a series of tepid compromises. To maintain a semblance of limiting migration, in 1875 Congress passed the Page Act, which limited the migration of Chinese women. The United States also negotiated a reversal of prior treaty stipulations to allow American officials, for the first time, to regulate the migration of Chinese workers. Then, in 1882, in response to deepening concerns of white violence, Congress passed the “Chinese Restriction Act,” now known as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

By preventing new workers from entering and barring existing residents from naturalization, the Act further crystallized distinctions between citizens and aliens, stoking existing racism, economic anxiety, and xenophobia. Local officials faced the impossible task of regulating the San Francisco harbor and the extensive border between U.S. territories and Canada. Consequently, they turned to white townspeople in San Francisco and the Washington Territory to report on their neighbors and co-workers. This form of border control proved unreliable, as the white townspeople tended to target Chinese workers indiscriminately, which in turn exacerbated racial tensions in previously integrated neighborhoods and workplaces. When violence broke out and officials failed to condemn it, they effectively recognized white vigilantes as extensions of federal and state border regulation.

Especially in the Pacific Northwest, where white locals couldn’t yet vote in national elections, the movement’s leaders justified racial violence as a valid form of political action. The federal government did little to discourage them. During the Rock Springs Massacre of 1885 in the Washington Territory, white miners killed 28 Chinese workers, wounded 15, and forced out hundreds before they set Chinese living quarters on fire. Emboldened by news reports of the incident, white vigilantes in Tacoma banded together with city officials to announce the “peaceful” and “business-like” removal of Chinese residents.

Though Tacomans would make death threats, loot and burn down homes, and drive out all but one Chinese resident, anti-Chinese editorial staff on the LA Times and Tacoma Daily News, among other local papers in the West, wrote up the episode as a successful, non-violent blueprint for Chinese expulsion. The “Tacoma method” would inspire vigilante expulsions of Chinese communities all over the West Coast and Pacific Northwest; by Lew Williams’s tally, over 200 cities and towns saw similar incidents between 1885 to 1887.

Concerned about the spread of anti-Chinese violence in the United States and anxious to prevent a mass return of migrants, Chinese officials proposed in 1886 to ban Chinese laborers from leaving China if they intended to move to the United States. Simultaneously, Congress came under pressure to resolve the “Chinese Question” before an upcoming election. Instead of addressing intensifying violence, U.S. lawmakers saw the Chinese self-ban as a convenient opportunity to extend the 1882 legislation; in 1888 the Scott Act passed, stipulating that even Chinese workers with valid return certificates could not re-enter the United States. American commercial expansion and white nationalism were no longer mutually exclusive—they were now entirely compatible.

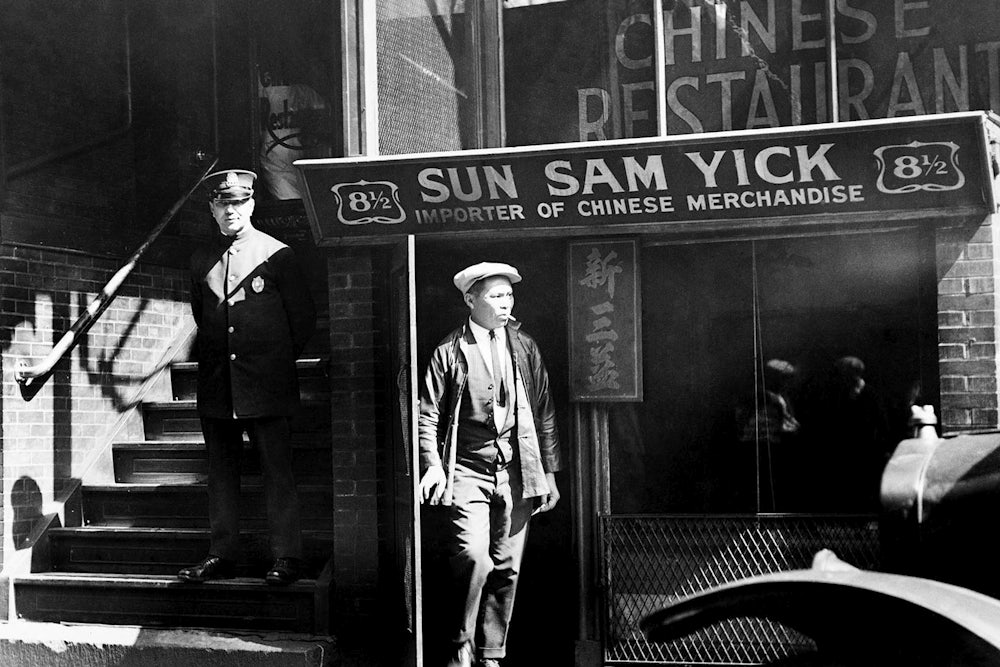

The legislation formulated during this period paved way for the systematic surveillance of Chinese and other Asian immigrants in the United States. In 1892, the Geary Act required all Chinese migrants to undergo a registration system and provide “affirmative proof” of their right to reside on U.S. soil. This was unheard-of at the time. The registration system “effectively transformed the Chinese Exclusion Act into a Chinese expulsion act by targeting long-term residents,” Lew-Williams writes. “Border control was no longer confined to the nation’s borders but stretched into the interior.”

Exclusionary policy drove migration underground, increased human trafficking, and added to the physical and psychological dangers that already accompanied the journey. Violence and exclusion not only continued within the United States, but also overseas in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, following the end of the Spanish-American War. Chinese communities—some of which had existed in integrated neighborhoods and workplaces—were forced into hyper-segregated enclaves, while some individuals were cut off from their communities altogether and scattered among hostile, white-dominated areas across the country. Even decades after Chinese Exclusion ended in 1943, the effects are marked: Less than 10 percent of Chinese-Americans today can trace their lineage back three generations in the United States. In Tacoma, a decade-long search for descendants of the Tacoma Chinese has yielded none.

The majority of Chinese in America today arrived along with other East Asians, South Asians, and Southeast Asians after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which remade the socioeconomic and ethnic makeup of Asians in America by prioritizing family reunification and skilled workers. The influx of upwardly mobile immigrants became an opportunity for both conservatives and liberals to retire the “yellow peril” stereotype and recast Asian Americans as “successful immigrants,” politically amenable and capable of assimilating into white, middle-class America. Many Asian Americans, who had been stigmatized as communist infiltrators during the Red Scare of the ’50s, also promoted the model minority narrative to avoid further exclusion and violence. The careful fabrication of Asian success has in turn been used both to justify racism against other minorities and to erase socioeconomic and generational differences within Asian American communities.

The model minority myth does not reflect the broader history of Asians in the United States, from the 60-year-long history of Chinese exclusion, to Japanese incarceration, to the radical Asian American movement. This history is vital, but very little of it is taught in schools: A 2015 survey of American government textbooks revealed that on average, Asian American and Pacific Islander issues made up less than 1 percent of the pages. If current first- and second-generation Asian Americans are estranged from the decades-long history of Chinese exclusion, that distance, too, has been constructed by white violence, federal failure, exclusionary policy—and by continued historical erasure.

Today, Asian American communities are the fastest growing populations in the United States, but have some of the lowest voter turnout rates compared to other minorities. Increased outreach and accessible translated ballots will be crucial to mobilizing Asian Americans as a political force, but meaningful civic engagement begins first with historical and political understanding. It will be increasingly necessary for Asian Americans to consider the historical roots of structural inequalities that continue to shape America. That means not only breaking down historical and present-day stereotypes, but learning to see what is missing from pictures of the past.