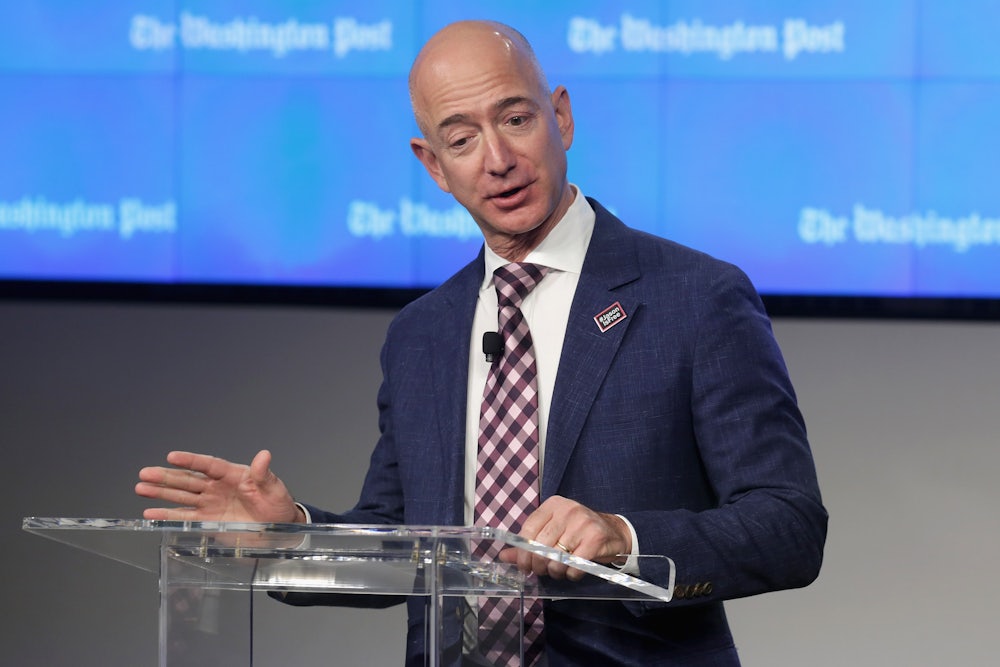

Since Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos purchased The Washington Post in 2013, the newspaper has been one of the great—and few—success stories in media, legacy or otherwise. The size of the paper’s staff has grown to over 800, and it has opened bureaus around the globe, most recently in Hong Kong and Rome. In 2015 it beat its arch-rival The New York Times in terms of readership (though the Times has since regained the upper hand), and it has been profitable for two years. No one, in 2018, seems to really know how to run a lucrative, well-read, daily publication, but The Post suggests that one way is to be owned by the richest man in the world.

With Google and Facebook sucking money out of newsrooms, the Bezos model has become increasingly popular. Steve Jobs’s widow Laurene Powell Jobs purchased a controlling stake in The Atlantic last year, while billionaire Patrick Soon Shiong bought The Los Angeles Times this spring. With subscriptions falling, private equity bleeding local newspapers dry, and behemoths like Gannett and Tronc (the previous owner of The Los Angeles Times) teetering, having a wealthy patron is a more appealing option than it was just a few years ago. Led by editor Marty Baron and economically secure, the Post has been a beacon for journalists as well as readers.

But, as Vanity Fair reported last week, “a crack appears to be developing in this cheery facade.” The Washington Post’s union, which represents hundreds of non-management positions at the paper, has been working without a contract for the past twelve months. Earlier this month, 400 of their members signed an open letter asking for pay bumps and better retirement benefits. (Full disclosure: Non-management employees of The New Republic are represented by the News Guild, which is, like the Post’s union, part of the Communication Workers of America.) Bezos is in the midst of a very tough negotiation with significant implications not only for the future of the Post, but also an entire industry that is increasingly looking to billionaires for salvation.

The wealthy media owner is often presented as either a philanthropist stepping in to save a legacy brand from oblivion, or as an opportunist trying to launder their reputation and influence the political conversation in their favor. Bezos leans toward the former. Citing the paper’s grandiloquent motto—“Democracy Dies In Darkness”—he has said that owning the Post is his civic responsibility. “Certain institutions have a very important role in making sure there is light, and I think the Washington Post has a seat, an important seat to do that, because we happen to be located here in the capital city of the United States of America,” he said in 2016.

However, he has also made clear that the Post is not a charity. “This is not a philanthropic endeavor,” Bezos said last year. “For me, I really believe, a healthy newspaper that has an independent newsroom should be self-sustaining. And I think it’s achievable. And we’ve achieved it.”

Drawing lessons from his day job, Bezos also said that the Post should treat its audience the way Amazon does; Amazon routinely tops surveys judging consumer satisfaction. “We run Amazon and The Washington Post in a very similar way in terms of the basic approach,” Bezos said. “We attempt to be customer-centric, which in the case of the Post means reader-centric. ... If you can focus on readers, advertisers will come.”

These factors—civic responsibility, a commitment to the customer, and an insistence on running the Post like a business—have contributed to Bezos’s reputation as the defender of one of America’s most important publications. They have also, combined with investments in new positions and bureaus, apparently made him popular with much of the staff. The union dispute is the “first tangible conflict,” one Post journalist told Vanity Fair’s Joe Pompeo—a fairly impressive feat in and of itself, given that Bezos has owned the newspaper since October of 2013.

Post staffers have been grateful to have an owner willing to invest in the paper. Bezos’s investments, moreover, worked for both him and the staff—they were designed to increase the paper’s relevance and profitability. Still, they were made on Bezos’s terms. When contracts were last negotiated with the paper’s union in 2015, the Post had still not returned to profitability. Pensions were frozen then; the Post’s retirement plan is the central source of conflict in the current dispute, as are a lack of employment protections and cost-of-living increases. In recent days, Post Union Vice Chairman Fredrick Kunkle told me, waivers—the paper is insisting that, in order to receive severance pay, departing employees sign an agreement agreeing not to sue the company—have become a sticking point.

In its second negotiation with the Bezos-owned Post, the union is getting a better sense of its owner’s priorities. “We are in this position where, on the one hand we are all very thankful to this day that Jeff Bezos bought the Post, invested so much money in it, and has given us the long runway he talked about,” Kunkle said. “But we’re also very concerned that even as the Post is on the rise, the terms and conditions for people working here are becoming worse. That’s the place we are right now, and it makes us feel uncertain.” Earlier this month, over 400 Post employees signed a letter to Bezos asking for better compensation and benefits. (A spokesman for the Post declined to comment.)

A major concern is that the lack of basic workplace protections and benefits in the tech sector—Amazon very much included—is at the core of Bezos’s strategy for operating the Post as well. Bezos is not directly involved in the negotiations, which are being led by the newspaper’s general counsel. But he is very much a creature of Silicon Valley. He has been hostile to organized labor at Amazon, which has been singled out for its grueling corporate culture and for the alarming conditions of many of its fulfillment centers. In the Post’s debates over pensions and NDAs, as well as the arduous contract negotiation itself, it’s easy to see the influence of Silicon Valley’s hardball approach to labor.

The Bezos who bought the Post is no different from the Bezos who upended the book publishing industry, who has run roughshod over local and federal tax law, and who has kept workers at his fulfillment centers in conditions reminiscent of the 19th century. He may still be the best option for The Washington Post, but he also represents the flaws of a model that relies on the good graces of extremely wealthy people who have their own highly developed views on how to run a business.

Bezos may have created a new model for media ownership, combining the old school titan of industry with tech-based ideas about employment and content production; but the result is familiar. “It’s the age-old strategy of people who own factories and means of production,” Kunkle said, “trying to get the most out of the people they employ while giving them the least they can get away with.”