A seven-year legal battle over Texas’s legislative maps largely ended on Monday, as the Supreme Court rejected almost all claims that Republican lawmakers in the state had drawn electoral districts to intentionally dilute minority voters’ influence—otherwise known as racial gerrymandering. The decision in Abbott v. Perez rounds out a string of defeats at the high court this term for voting-rights advocates. It also vindicates Texas Republicans’ strategy to shield a discriminatory electoral map from judicial correction.

In 2011, following the 2010 census, Texas lawmakers redrew the state’s legislative and congressional districts. A group of black and Hispanic Texans quickly mounted a legal challenge to the new map, arguing that the state’s Republican lawmakers had engaged in racial gerrymandering by redrawing districts to bolster white Texans’ voting power. With the 2012 election imminent, a federal court made minor alterations to the 2011 map for use in that year’s races.

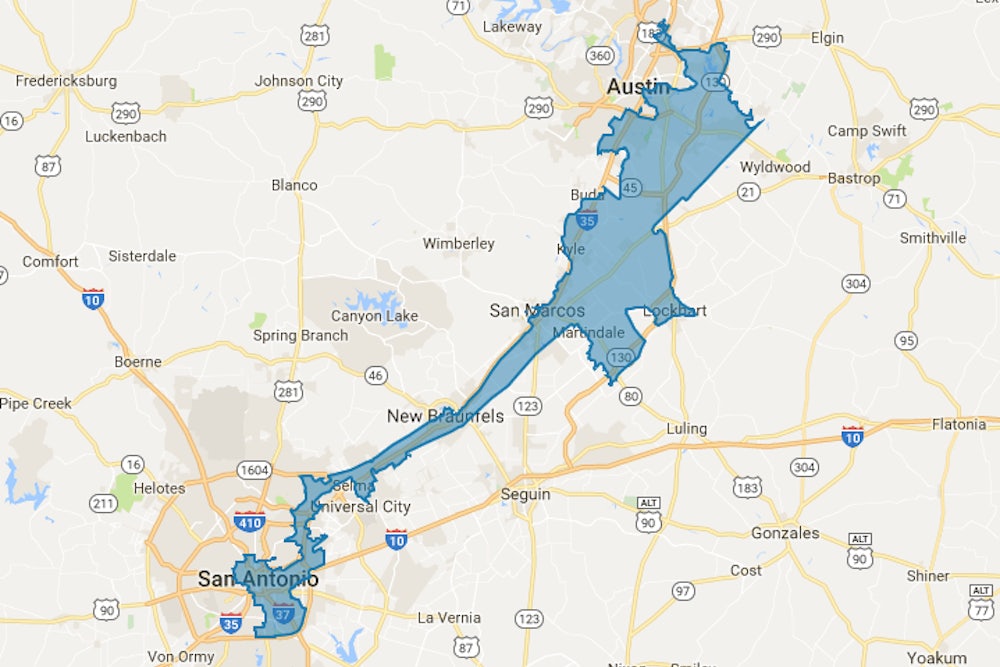

When Texas Republicans returned to the legislature in 2013, they adopted the court’s interim maps as the permanent maps, with only a few alterations. After the courts later ruled that the 2011 maps—including the 35th Congressional District, shown in the image above—had been drawn with discriminatory intent, the state argued that the 2013 maps weren’t affected because they had been largely drawn by the courts themselves. In effect, Republicans had laundered a racially gerrymandered map through the judicial system.

The lower courts weren’t fooled. A three-judge panel ruled last year that the 2011 map’s “taint” hadn’t actually been removed from the 2013 map, despite the state’s claims. But Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority on Monday, said the lower court had committed a “fundamental legal error” by placing the burden to prove the maps’ constitutionality on the state instead of the plaintiffs who brought the lawsuit.

“The 2013 Legislature was not obligated to show that it had ‘cured’ the unlawful intent that the court attributed to the 2011 Legislature,” he wrote. “When the congressional and state legislative districts are reviewed under the proper legal standards, all but one of them, we conclude, are lawful.” Justices John Roberts, Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch joined his opinion.

In a forceful dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said the majority had manipulated prior rulings and the evidentiary record to reach its desired outcome. “As a result of these errors, Texas is guaranteed continued use of much of its discriminatory maps,” she wrote, joined by justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Elena Kagan. “This disregard of both precedent and fact comes at serious costs to our democracy.”

Sotomayor’s 46-page dissent effectively accuses the majority of a bit of gerrymandering of its own, this time to portray the factual record in its favor. At times, she wrote, the majority selectively quotes evidence that exonerates Texas lawmakers of discriminatory intent. In other instances, the court’s conservatives ignore a broad swath of the factual record that suggests the state’s Republicans sought to preserve the 2011 maps’ flaws as much as possible when drawing the 2013 maps.

At one point, for example, Alito criticizes the lower court for surmising that Representative Drew Darby, the chair of the Texas House Redistricting Committee in 2013, hadn’t taken criticism into account during the legislative process. Darby had told other lawmakers he wanted to keep amendments to the map at a minimum before it was passed. The lower court concluded, based on that and other statements, that he had “willfully ignored those who pointed out deficiencies” in the new maps.

“That Darby generally hoped to minimize amendments—so that the plans would remain legally compliant—hardly shows that he, or the Legislature, acted with discriminatory intent,” Alito wrote. “In any event, it is misleading to characterize this attitude as ‘willful ignorance.’ The record shows that, although Darby hoped to minimize amendments, he did not categorically refuse to consider changes.”

Sotomayor paints a less favorable picture of Darby’s legislative wrangling in her dissent, arguing that he took no apparent effort to remedy the 2011 maps’ discriminatory effects. “In fact, the only substantive change that the Legislature made to the maps was to add more discrimination in the form of a new racially gerrymandered [House District] 90, as the majority concedes,” Sotomayor wrote. (Emphasis hers.) She went on:

The legislative hearing that the District Court cited shows that Representative Darby: told certain members of the Legislature that changes to district lines would not be considered; rejected proposed amendments where there was disagreement among the impacted members; rejected an amendment to the legislative findings that set out the history underlying the 2011 maps and related court rulings; acknowledged that the accepted amendments did not address concerns of retrogression or minority opportunity to elect their preferred candidates; and dismissed concerns regarding the packing and cracking of minority voters in [four state house districts] stating simply that the 2012 court had already rejected the challengers’ claims respecting those districts but without engaging in meaningful discussion of the other legislators’ concerns.

Alito didn’t hide his frustration with Sotomayor’s critique that he wasn’t faithful to the factual record. “The dissent seems to think that the repetition of these charges somehow makes them true,” he wrote in a footnote. “It does not. On the contrary, it betrays the substantive weakness of the dissent’s argument.”

The court has expressed its discomfort with partisan gerrymandering from time to time. A 2015 ruling described it as “inconsistent with democratic principles.” But the justices have never struck down an extreme partisan gerrymander, largely because there wasn’t a clear test to determine when ordinary redistricting tactics go too far. Many legal observers hoped that the justices would resolve the question this term, when three redistricting-related cases made their way to the court’s docket.

In Gill v. Whitford, a group of Wisconsin voters asked the justices to strike down a legislative map that gave Republican state lawmakers a nearly insurmountable structural advantage. Benisek v. Lamone also centered on partisan gerrymandering, this time at the federal level: Maryland Republicans challenged a single congressional district that had been redrawn by Democrats to bolster their party’s prospects there. But the court unanimously punted Gill back to the lower courts for further hearings and signed off on a federal judge’s decision to not issue an injunction in Benisek.

Perez rounded out the court’s treatment of the issue. Racial gerrymandering in its modern context is a form of partisan gerrymandering: Black and Hispanic voters tend to vote overwhelmingly for Democratic candidates, a phenomenon that helped re-elect Barack Obama in 2012 even as he received only 39 percent of the white vote. As a result, legislative maps that weaken those voters’ electoral influence also give Republicans a structural advantage.

The practical impact of Monday’s ruling is temporary. Like clockwork, the United States conducts a census every ten years to provide a snapshot of where the nation’s residents live. States use that snapshot to update their legislative maps for population shifts. The U.S. holds federal elections every two years, so those maps are used at least five times before another decennial census starts the process anew. Voters have already cast ballots in three federal elections so far based on maps drawn after the 2010 census.

For black and Hispanic Texans, however, the effects will be felt at least twice more. “Those voters must return to the polls in 2018 and 2020 with the knowledge that their ability to exercise meaningfully their right to vote has been burdened by the manipulation of district lines specifically designed to target their communities and minimize their political will,” Sotomayor wrote. In other words, the Republicans’ gambit worked.