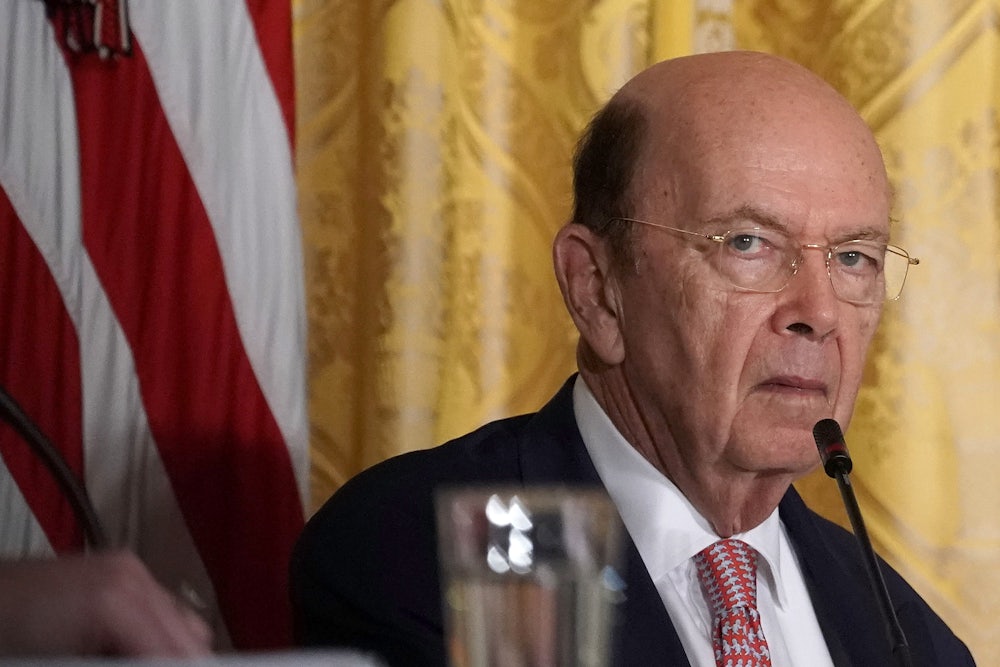

Days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, the Office of Government Ethics released an agreement with Wilbur Ross, then the nominee to head the Commerce Department, in which the octogenarian tycoon agreed to divest from a significant number of his holdings and step down from the boards of over 20 companies in which he held financial interests. Though Ross’s divestment should be considered the bare minimum for cabinet members, it nevertheless stood in contrast to the incoming president’s refusal to divest from his companies and persistent financial obfuscation. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat, told him, “You have really made a very personal sacrifice. Your service has resulted in your divesting yourself of literally hundreds of millions of dollars.”

But Ross made no such sacrifice. Earlier this week, Forbes reported that Ross had maintained multiple investments that constituted significant conflicts of interest, including ownership stakes in several Chinese-owned enterprises, a Cyprian bank being investigated by special counsel Robert Mueller, an auto parts company affected by Trump’s changes to trade policy (which Ross, as secretary of Commerce, is overseeing), and a shipping company with substantial ties to Russian oligarchs (who are close to Russian President Vladimir Putin).

The assets that Ross has formally divested, moreover, are being managed by a trust—meaning that Ross did not really divest from them at all, since he still knows which assets will return to his control when he leaves government service. Adding insult to injury, Ross even attempted to profit off his disclosures, shorting stock in the shipping company after being informed that his holdings were about to be made public last fall.

These revelations have resulted in something less than a media firestorm, thanks in large part to the outcry surrounding the Trump administration’s policy of separating migrant families at the border. But Ross’s brazen corruption is also part of a larger story. From EPA chief Scott Pruitt’s use of his office for personal gain—to say nothing of his purchasing expensive lotions and “tactical pants”—to the president’s own murky financial assets and connections, corruption is as much the story of the Trump administration as its cruelty toward minorities.

Ross’s ties to Russian oligarchs were first made public last fall, when the Paradise Papers revealed that he owned a stake, via a “chain of offshore investments,” in Navigator Holdings, a shipping company with deep connections to Putin’s inner circle, including some under U.S. sanctions. “I don’t understand why anybody would decide to maintain this kind of relationship going into a senior government position,” Daniel Fried, who served as secretary of state under George W. Bush, told The Guardian. “What is he thinking?” Ross’s press secretary, meanwhile, dismissed the connection, claiming that Ross “recuses himself from any matters focused on transoceanic shipping vessels.”

But it was Ross’s response to the revelation of his holdings, as revealed by Forbes, that is most shocking. Ross placed a short on Navigator’s stock days before his connection became public—meaning he was betting it would fall in value—a move that essentially means he was doubling down on corruption. Whether it was lawful or not is a subject of debate, though it could fall under the category of “insider trading.” But it is certainly unethical behavior for a public servant, particularly a cabinet member.

Ross said that his divestment from Navigator Holdings was pre-planned, making the timing coincidental. That may very well be true, but Ross’s denial contained more than a little hair-splitting. “Insider trading requires action be taken based on non-public information about a particular company,” Ross told CNN. “The reporter contacted me to write about my personal financial holdings and not about Navigator Holdings or its prospects. I did not receive any non-public information due to my government position, nor did I receive any non-public information from a government employee. Securities laws presume that information known to or provided by a news organization is by definition public information. The fact that the reporter planned to do a story on me certainly is not market moving information.”

Ross is arguing that because a news organization knew about his holdings, even though it had not made that information public, this could not be insider trading. It was, in essence, already public information. Whether that will hold up in a court of law remains to be seen.

Then there’s the Luxembourg-based International Automotive Components Group (IAC), which Ross created by merging a number of auto parts companies in 2006. In the fall of last year IAC closed a joint venture with a Chinese state-owned company. “As part of the deal,” Forbes reports, Ross’s company “took a 30 percent interest alongside a state-owned company named Shanghai Shenda and got roughly $300 million in cash.” This is a problem because Ross is currently investigating, at President Trump’s behest, whether or not the United States should tax imports on foreign cars. Ross’s findings could very well be informed by his family’s holdings in IAC, which will ultimately undermine whatever Ross recommends.

While Republicans in Congress have largely looked away from corruption within the Trump administration, Ross is perhaps uniquely vulnerable here, given the general lack of appetite for a trade war with China in Congress. So far, congressional Republicans have been unable to sway the president from protectionism, but Ross’s holdings have given them an opening.

The opening is even larger for Democrats, for whom corruption remains a potent message heading into the midterms (and 2020). Ross’s self-dealing and conflicts of interest should be part of a larger mosaic, encompassing Trump’s blatant use of the presidency for economic gain. The Russia connection, when it comes to Ross, is also tantalizing, but the larger point is this: Ross, like so many in the administration, is compromised not by connection to a foreign power, but by his own financial interest.