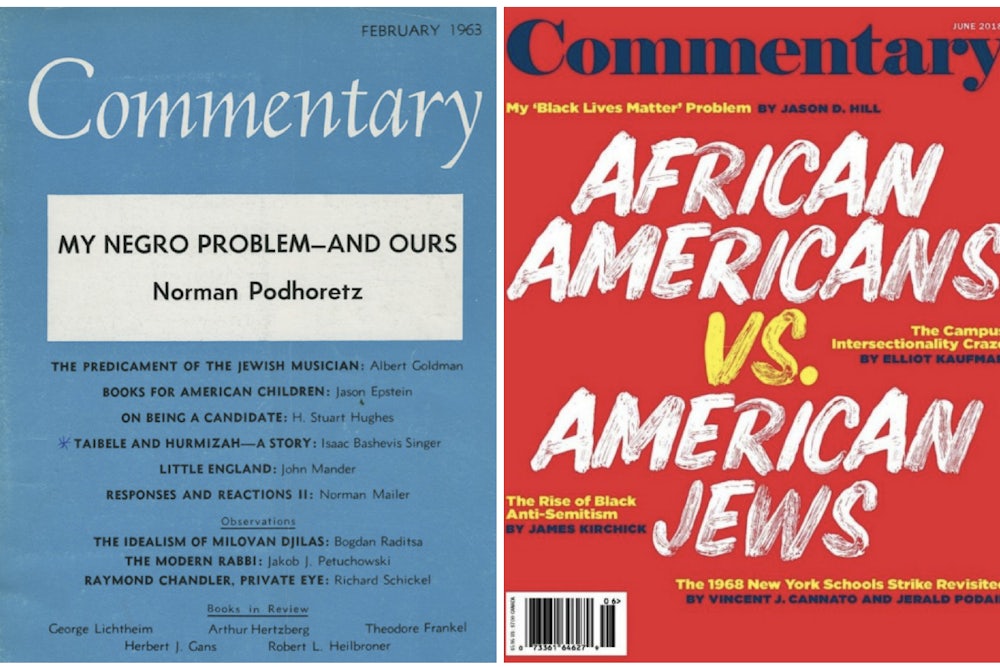

In a notorious 1963 essay titled “My Negro Problem–And Ours,” Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary, wrote of “the insane rage” he felt “at the thought of Negro anti-Semitism.” Podhoretz didn’t elucidate why “Negro anti-Semitism,” which manifested itself most visibly in the ravings of the Nation of Islam, should be any worse than white anti-Semitism—which, after all, was responsible for centuries of persecutions, pogroms, and, ultimately, the Holocaust. But in the pages of Commentary magazine, which Podhoretz edited from 1960 to 1995, other writers frequently took up the theme, airing their anxiety that the rise of African-American political activism would undermine the interests of Jewish Americans.

Commentary magazine is now edited by John Podhoretz, Norman’s son. And its June issue, which came online last month and began receiving critical attention this week, is about racial tension. “African Americans vs. American Jews,” the cover announces.

Last night, Black Jews led Jews of all colors through the most powerful seder I've ever seen.

— Rafael 🔥 (@rafaelshimunov) June 15, 2018

Also last night some sad lonely men with dusty, cobwebbed ideas at @Commentary magazine dedicated an entire issue to villify all Black people and erase Black Jews. #JuneteenthSeder pic.twitter.com/LxwDUjenIC

In “My ‘Black Lives Matter’ Problem” (an implicit allusion to the title of the elder Podhoretz’s essay), Jason D. Hill argues that “the kind of dependency that Black Lives Matter promotes lays the groundwork for personal failure”—a strange claim, since political activism would seem to work against dependency. In another entitled “The Rise of Black Anti-Semitism,” James Kirchik (formerly a staffer at The New Republic) condemns an “increasingly fatalistic progressivism” which is “willing to make common cause with all manner of illiberal and regressive political forces provided they hew to the party line.” For example, he cites reluctance of a few figures to condemn Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.

A third deals with the 1968 New York school strike, at which black activists who called for greater community control in hiring processes clashed with Jewish union leaders who wanted to protect the existing system of seniority.

It’s worth revisiting the history of Commentary magazine to see how tired and troubling the current arguments are. In Norman Podhoretz’s original 1963 piece, he bravely acknowledged the formative force of white supremacy in his own thinking, creating a bedrock racism that was impossible to overcome. “The hatred I still feel for Negroes is the hardest of all the old feelings to face or admit, and it is the most hidden and the most overlarded by the conscious attitudes into which I have succeeded in willing myself,” Podhoretz wrote. Podhoretz’s failure came after that essay, when he failed to realize that the internal racism he had rightly admitted to still guided his editorial choices and the ways in which he framed political issues. To be sure, Podhoretz wasn’t alone in that failure. Many magazines, not least of all The New Republic, succumbed to a similar politics of racist resentment in the face of black militancy and African-American cultural resurgence.

In 1969, Milton Himmelfarb wrote an article in Commentary asking “Is American Jewry in Crisis?” where he used the New York teacher’s strike to argue that the American “Establishment” had decided to sacrifice Jews in order to appease rising black militancy. (This is the exact same argument Commentary repeats in its latest issue). The “Establishment,” Himmelbarb reasoned, probably thought this way:

Who will be hurt most? Jews. Well, fair is fair, and as between blacks and Jews we have no reason to reproach ourselves when we give preference to the blacks. It is not as though the Jews were suffering. They have done pretty well for themselves, and they have no right to complain if they are now asked to move over and make room for someone else.

Himmelfarb made the underlying argument that American pluralism is a zero-sum game: If blacks rise, Jews must suffer. He in effect made Jewish self-interest a wedge to promote anti-black politics. This is a now a familiar tactic the right uses, as witness recent attempts to use the legitimate issue of discrimination against Asian-Americans to destroy affirmative action in college education.

Working from the underlying assumption of a zero-sum game, Commentary has frequently stoked tensions between American Jews and African Americans. “Black Anti-Semitism on the Rise,” ran a Commentary headline in October 1979. (This is rehashed as “The Rise of Black Anti-Semitism” in the current issue). “Black Anti-Semitism and How it Grows” ran a 1994 article. “Facing Up to Black Anti-Semitism” was the version used in the following year.

Black anti-Semitism, which is very evident in figures like Louis Farrakhan, should be condemned whenever it expresses itself, as should all other forms of anti-Semitism. But, in an age where the President of the United States offers rhetorical coddling of neo-Nazis, as Donald Trump did after the Charlottesville attack, Farrakhan is far from the most powerful promoter of anti-Semitism in America. Trump has re-tweeted Nazis and anti-Semites. He has bandied about anti-Semitic dog whistle terms like “globalists” (applying them to Jews in his administration). He has helped elevate the alt-right to national prominence by hiring one of their chief political allies, Steve Bannon, to be a campaign CEO and White House advisor.

Abraham Foxman, retired director of the Anti-Defamation League, argues “Trump is not an antisemite and he is not responsible for the antisemites, but he emboldened them to go public. He is responsible for that and he is the only one who can put the genie back in the bottle.” This is a just conclusion, and stands in contrast to the whitewashing done by Commentary where we are told, in an article criticizing “black anti-Semitism” that “For all his many faults, Donald Trump has never ‘questioned the humanity,’ either metaphysically or biologically, ‘of Jewish people.’” While technically true, it doesn’t begin to grapple with the way that Trump, even without being an anti-Semite, is still a fellow traveller of anti-Semitism.

In the age of the alt-right, fighting anti-Semitism is an urgent problem. Unfortunately, Commentary magazine doesn’t seem interested in the most politically potent form of contemporary anti-Semitism. Instead, the magazine seems to be serving up the 1960s, reheated.