In 2001, after signing the papers that would finalize her much-publicized divorce from Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman emerged into the afternoon sunlight outside her LA lawyer’s office, raised her arms, and shouted for joy. At least, that’s the possibly apocryphal story behind an iconic set of paparazzi photos of Kidman looking triumphant in lime green capris and a sheer floral top that makes the rounds on social media every few months. The breakdown of Cruise and Kidman’s marriage is a familiar story: Stars are just like us, after all, and their divorce rates are even higher. But if celebrity marriages are more likely to end than ordinary ones, it may not be due only to the warping effects of fame. Like the star system itself, America’s version of the no-fault divorce was invented in California. (In the Soviet Union, the no-fault divorce had existed since 1918).

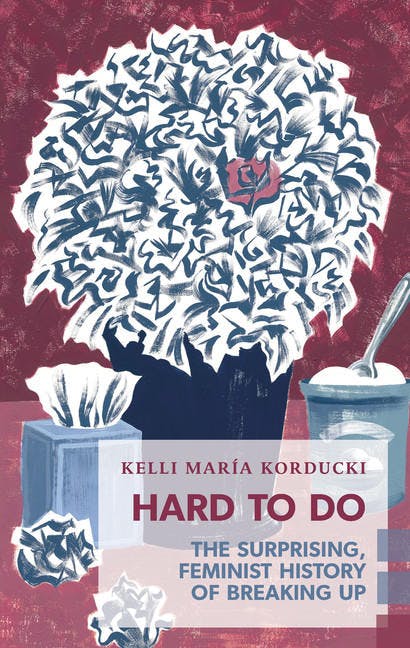

Exactly 30 years before Kidman celebrated her newfound freedom, then-governor of California Ronald Reagan—himself a Hollywood divorcé—signed into law a piece of legislation that simplified the grounds for divorce: A couple could split because of “incurable insanity” or “irreconcilable differences.” The latter, as Kelli María Korducki writes in Hard to Do: The Surprising Feminist History of Breaking Up, “removed the requirement for a divorce petition to argue spousal wrongdoing on behalf of either partner,” a rule that had made divorce in America, up to this point, “a years-long legal hassle contingent on proving, through evidence provided and argued before a state court, a narrative of victimhood and perpetration.” That hassle had fallen most heavily on the shoulders of women, who were more often burdened with proving their suffering, and whose suffering was so pathologized it could be easily dismissed. (In 1836, a New Hampshire court refused to grant a divorce to a woman whose husband had locked her in a basement and beaten her with a horse whip because they alleged her “high, bold, masculine spirit” had driven him to it).

The no-fault divorce is just one of the turning points cited in Hard to Do, which charts the history of romantic dissolution in North America and the United Kingdom primarily through the legal and economic forces that have permitted women to initiate breakups—or, more often, prevented them from doing so. Korducki’s investigation is framed by the story of her decision to leave a “kind, sweet, smart and good” man she “had loved and lived with for nearly a decade.” It was not a decision made lightly; she consulted with friends, family, a therapist, and even a Dear Sugar column, in which a then-anonymous Cheryl Strayed advised three women at similar crossroads. Even so, the breakup “persisted in destroying [her] entire life over the course of many months.” Why, she wanted to know, did walking away feel “like scoring big in the lotto and torching your winnings for sport?”

Korducki’s choice of words here is pointed: Despite the gains women have made, the odds remain stacked against them when it comes to striking out on their own. Nicole Kidman memes aside, mainstream messaging about breakups is rarely so celebratory. A brief journey into the world of romantic self-help reveals a genre “conspicuously short on books that speak to a woman’s right to call it quits, let alone her desire to”—despite the fact that women who file for divorce report being happier afterward, while the opposite is true for men. When it comes to the question of women’s romantic autonomy, our cultural imagination remains limited. Hard to Do illuminates the capitalist logic that underpins intimate relationships, and asks what it would take for us to stop viewing breakups as failures.

The history of romantic partnership maps neatly onto the industrial and economic history of the last two centuries. Up to that point, marriage had been primarily a pragmatic institution: a legal union undertaken in the interest of preserving family wealth, property, bloodlines, and social classes. In fact, love—and desire in particular—was once seen as anathema to marriage; as Plutarch recorded in his Life of Cato the Elder, the Roman statesman Manilius was kicked out of the Senate for kissing his wife in front of their daughter in the second century BCE. But with the Industrial Revolution, alternative paths to wealth opened up and people flocked to new urban centers in pursuit of them, disrupting older kinship structures. Meanwhile, the Enlightenment encouraged the pursuit of individual rights and happiness. The love-marriage was born.

Still, courtship and calling, both of which occurred within the controlled space of the family home, remained the dominant form of socializing between young single men and women until the turn of the twentieth century. As Moira Weigel recounts in Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating (a kind of corollary to Hard to Do), the stock market crash of 1890 precipitated a great flood of women from rural or agrarian backgrounds leaving home to find work as garment workers, laundresses, salesgirls, and secretaries in the city, accelerating a wider population shift from rural to urban areas. By 1900, more than half of American women worked outside of the home.

This put working-class men and women in closer contact than ever before, on the job, in transit, and in the new spaces for leisure—the cinema, the soda fountain, the amusement park—that sprang up to absorb their pocket change. Because women, then as now, had less spending power than men, many would accept dates on the basis of a “treat,” earning them the nickname “Charity Girls” (along with lots of hand-wringing). “Where older models of courtship were structured around a ritualized exchange of domestic niceties,” Korducki writes, “dating was built on the public consumption of goods and services. Dating, in short, was good for the growing economy.” That remains true today when in the United States, the online dating industry alone generates $2 billion in revenue each year.

If marrying for love and mixed-gender fraternizing outside of the home are relatively new, splitting up has even less precedent. Divorce remained exceedingly rare until the first liberalizing laws of the nineteenth century; breaking up in the more colloquial sense is not even a century old. The lean years of the 1920s and 30s had encouraged a competitive model of dating that was not necessarily seen as a precursor to marriage: while the ability to afford sodas, hamburgers, and Vaudeville tickets had set daters apart in the early 20th century, during the post-Depression years, dates themselves became a kind of currency. “Dating prolifically was the one way to keep up their stock,” Weigel writes, “even as any given date became less likely to lead to a permanent arrangement.”

It was only with the economic boom of the postwar years that the break-up came into being. Suddenly, many young men and young women had the means to pay for a night out, and the importance of telegraphing popularity by racking up dates waned. This created what Weigel calls “a kind of romantic full employment.” Rather than filling their date books and dance cards with as many potential partners (and potential “treats”) as possible, young people began pairing off. “Steadies invented the Breakup,” Weigel argues. “Going steady was a prerequisite for that specific kind of heartache.” In an era where breakups furnish lucrative apps, reality TV concepts, Hollywood blockbusters, and entire music careers it comes as something of a revelation that we’ve only been doing this for some 60-odd years.

The official history of marriage and dating, Korducki points out, has also been an exceedingly white, heterosexual one. In the antebellum South, enslaved black men and women were legally considered property and were unable to formally marry at all; although informal marriages among enslaved men and women were common, an estimated two-fifths of these partnerships were forcibly broken up by the domestic slave trade. At the turn of the twentieth century, vice commissions frequently dispatched undercover officers to observe young men and women meeting up for dates (under the assumption that they were engaging in prostitution), but this surveillance paled in comparison to the violence those same officers frequently enacted in clandestine gay spaces. As Korducki puts it, “though we’re all inheritors of a history, some of us have longer threads on the rope’s frayed end.”

Still, with the admission the conversation might feel dull for anyone whose partnership choices have always been considered transgressive, Hard to Do speaks mostly to Korducki’s cohort, and my own: unmarried, heterosexual millennial women living in cities with at least a modicum of “disposable income and expendable time.” The unprecedented freedom such women now have to make or break relationships has raised the stakes, she reflects, when it comes to selecting a partner: “With autonomy comes great responsibility to either choose exactly right or to undermine the very existence of our own freedom to follow our hearts.” If there are now more methods of pairing up than ever, and more time in which to do it, there are also more ways to get it wrong. Such mistakes carry more weight in an increasingly atomized society, in which romantic partners are expected to fulfill multiple social and emotional needs—consider the ubiquity of the phrase “I can’t wait to marry my best friend!”

Of course, much of this freedom is illusory: While it’s become gauche to acknowledge explicitly the relationship between money and, well, relationships, the economy still exerts a powerful influence on our romantic lives. Dating apps like The League that cater exclusively to an “elite” clientele, but even the less exclusive ones tend to match people on the basis of shared tastes—in film, food, travel, or music—which tend to indicate class. And although women can now drink in bars unchaperoned and get a divorce, precarity continues to keep women in bad relationships. When unemployment rises, divorce rates drop proportionally. In an economic system that pays women less for their work than it pays men, sometimes leaving is just not financially viable.

Korducki, for her part, seems to have found, at least partly, what she wants. In the years since her breakup, she has moved away from organizing her life around a single romantic partner. In the book’s conclusion, she recounts instead the variety of relationships she now has: some intimate, others civic or neighborly. It’s a tentative step towards a different kind of future, one in which the emotional pressure we currently apply to romantic relationships is distributed more evenly across a wider social network. A future, in other words, that would render this book’s title moot.