The John McCain I came to know is a far more interesting, layered, complicated, farsighted, shrewd person than most of the portraits of him convey. And for all his unusual accessibility to the press and through them the public, a part of him remains impenetrable. A congenitally restless man, his clear preference was to keep moving, as if stopping to contemplate matters was something he wasn’t comfortable with. McCain reads books but he’s no deep intellectual; as a senator, which was when I knew him best, he’s been a man in motion, of action. “What’s next?” he’d quickly ask a staff member after a subject had been discussed or a bill had been passed. When he did stop to muse about the world or life it was usually in terms of his heroes—in particular Theodore Roosevelt, a man of action but also a reformer—and his reference point was most often his five and a half years in North Vietnamese prisons. His highest form of praise was to say to someone, “We’d have had fun in the camps.”

The scamp in McCain helped him survive “the camps,” and also put him at odds with the phony solemnities of politics. (Which also endeared him to members of the press, of which more in a moment.) Early one morning in January 2003, when he and I were alone in his office and I commented that victory was finally in sight in his eight-year fight for a campaign finance reform bill, his signature but far from sole issue in the early 2000s, McCain replied, quietly, “I don’t feel any sense of relief or happiness until it’s done.” And then he said something I’d never heard him say before: “I learned from prison, you don’t go too far high because then you go down.” He explained further: “While I was in prison, in 1968 LBJ stopped bombing in North Vietnam, and a peace conference was convened in Paris. All of us—all of us—were very high. The ensuing months and years taught us otherwise: Never get too happy or too depressed. I try to maintain tight rein on my emotions when in difficulty ever since.”

Since he was a man of prodigious energy and restlessness, even though the scars of his captivity in North Vietnam included a slight limp as well as arms that he can’t raise over his head, keeping up with McCain as he zoomed along the marble floors of the Capitol was a daunting challenge. When he managed a bill on the Senate floor, he rarely remained in his seat for long but instead darted about the chamber, talking to members on both sides of the aisle, taking their temperature, plotting, shooting the breeze, joking. Though he was reputed to have a towering temper, he calmed down almost as quickly as he blew up, and retained top staff members longer than almost anyone in the Senate—a measure I apply to elected members to ascertain what kind of person they are.

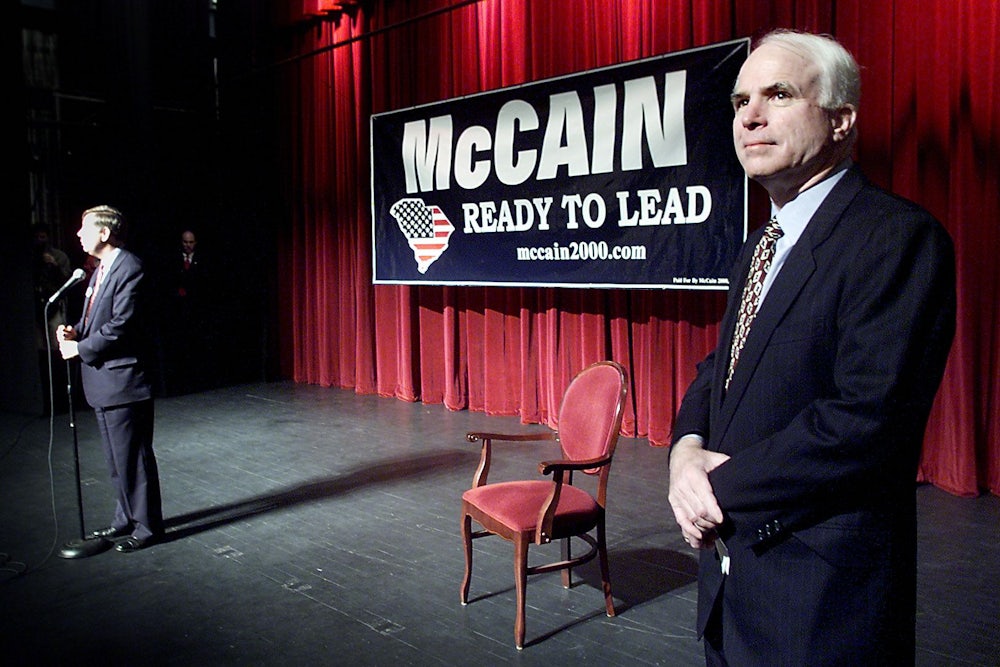

Brilliant as the concept was, I almost wish his 2000 campaign for the Republican nomination hadn’t commissioned the Straight Talk Express, the bus in which McCain sat in the back, yucking it up with the reporters who surrounded him as he traveled between stops. Yes, McCain is a funny man, a wise-cracker, above all accessible to the press, which he has called “my base.” The point of the Straight Talk Express was to break through the din of a presidential campaign, to guarantee him ample coverage, and to help make up for a shortage of funds in his difficult challenge against George W. Bush, the pick of the Republican establishment for the nomination. And it was a success in those terms. The bus device also gave McCain an opportunity to display himself as the rare politician unafraid to chatter with the press with no script or talking points or hovering aides anxious to redirect a question or clean up an answer or tape the conversation.

The more congressional aides that hover while a politician is being interviewed, the weaker he likely is. An aide immediately poses a wall between the politician and the reporter. I’ve been in a room with a member of Congress who had as many as six aides monitoring me as I interviewed him. (I didn’t go back for more.) Between January 2001 and early 2003, I spent the better part of two years hanging around McCain while he pursued a campaign finance reform bill, and an aide was never present unless she had brief business with McCain that had to be attended to at once. This isn’t to say that McCain was the only elected politician who would talk to a reporter without an aide present or recording, but his were among the most unalloyed conversations that one could find on Capitol Hill. And therefore the most interesting and instructive.

The Straight Talk Express also led to the stereotype of McCain as the happy warrior, the guy who was a lot of fun to be around. And that was about it. A strange hostility—on the part of some journalists who weren’t part of the rolling show, which I didn’t participate in, either—developed around McCain’s largely successful cultivation of the press, as if there were something wrong with that. Other politicians woo the press, but they’re either not as good at it or not as amusing to be around—or as direct. With McCain, reporters had little reason to feel that they’re being used, being spun a line that’s supposedly politically useful. McCain didn’t try to spin—and this was what drew reporters to him. There’s little more tiresome in covering politics than to have to try to remain polite while knowing that a politician is spinning you, purveying the party’s talking points of the moment; the spinning politician doesn’t get it that his machine-like response is more obvious than he may suspect and also an insult to the reporter who sees through it without difficulty. (“Does he really think that I’m buying this?”)

A great deal of the press attraction to McCain stems from the fact that he comes across as authentic. Not for him the curlicues of political language, or the carefully contrived evasions. The pomposity genes that so many politicians carry seem to have passed him by. By word or by facial expression he lets you know if he doesn’t care for another politician—most of the time. Though he didn’t show it I knew that he wasn’t especially fond of the Democratic co-sponsor of his campaign finance reform bill: Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold, who took himself very seriously and struck a pose of holier-than-thou to his colleagues, who were none too fond of him for that. But McCain was essentially stuck with Feingold as his Democratic co-sponsor, because few Democrats wanted to take the lead on closing off streams of money for their campaigns.

McCain wasn’t wildly popular with his Republican colleagues, though his mortal illness has softened the views of many of them. A maverick doesn’t tend to be adored by the conformists he’s mocking. McCain’s few Republican friends in the Senate in the early 2000s were Chuck Hagel and Fred Thompson, both of whom were among the four Republican senators who backed McCain over Bush for the 2000 nomination. (His very close friend Lindsey Graham was in the House at the time.) But even Hagel, who was ostensibly for campaign finance reform, put the knife into McCain by coming up with an alternative proposal that had the fingerprints of the Bush White House on it, and the Bush White House didn’t favor campaign finance reform—an issue McCain had fought Bush on during their nomination fight. When, one afternoon, McCain scooted across the hall on the first floor of the Russell Office Building to make peace with Hagel, though Hagel had just betrayed him, I asked an aide why he was doing that. The aide replied, “When you have as few friends up here as John does, you can’t afford to lose any.”

It’s not an overstatement to say that Karl Rove, Bush’s political consigliere, hated McCain. When the name of the Arizona senator came up in a conversation with Rove his face would redden and he’d choke out his attacks on him. McCain clobbered Bush in New Hampshire, which Bush was supposed to win, but then lost after a legendarily dirty fight in South Carolina in which McCain and his wife were the subjects of vile but untraced rumors. In early March of that year, after losing some big states to Bush, he dropped out of the race for the nomination—and declined to endorse Bush at the time; after some dancing around, he endorsed Bush at the 2000 convention, but produced an obviously forced smile during their few joint appearances. McCain emerged from the 2000 fight with an enhanced national reputation and campaign finance reform as his signature issue.

In the course of his 2000 campaign effort, McCain unexpectedly drew independents and some Democrats to him (this was of no use in the “closed primaries” in which only Republicans could vote, which was a great advantage for Bush). McCain noticed that there was an opening at the center, a vacuum to be filled by a leader beholden to neither party, a Ross Perot without the eccentricities. And so he and his longtime close aide and co-author Mark Salter carefully carved out a new place for him in American politics, the reformer who matched his unique way of talking and who saw that there was much to be done. By the summer of 2001, in addition to campaign finance reform, McCain was backing: a patients’ bill of rights, on which he joined Edward Kennedy; hearings on climate change and adequate funding for national parks; a proposal, with Connecticut Democrat Joseph Lieberman, to close the loophole in sales of guns in gun shows, an unusual position for a Western Republican to take; opposition to the size of Bush’s tax cuts for the wealthiest, arguing that the funds should be used to help the middle class; an effort, with current Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, to help patients get more access to generic drugs; and a proposal to stop gambling on college sports, in the belief that the practice corrupted the student athletes, which put him in opposition to the powerful gambling industry.

McCain didn’t expect to win all these fights but he saw a purpose in making them. When I asked him if he saw himself moving to a new place in American politics, McCain replied, “I don’t know. I think that if I do the best that I can, address the issues as best I can, the rest takes care of itself.” McCain mainly lived for the moment.

McCain hasn’t been an angel all his adult life. He dumped his first wife, Carol, who had waited during his long captivity for him to return from Vietnam, and who during that time suffered grievous injuries from an automobile accident. He left Carol (blindsided) to marry the beautiful Cindy Hensley, eighteen years his junior; Cindy’s father was a wealthy beer wholesaler in Arizona, where McCain decided to begin a new life and to get into politics. (His faithfulness to Cindy, with whom he has a close relationship now, was in open question in Washington in the early years of their marriage.) Carol and John McCain have remained good friends and those who’ve tried to get a negative word about him from her have inevitably failed. Carol openly backed him in his presidential campaigns.

McCain sees himself as principled, not a compromiser for political gain, and when he broke with that faith, as he did in 2000 when he ducked the heated question of whether the Confederate flag should remain flying over the South Carolina state capitol building, he felt lousy about it. At the time, he joined George W. Bush in saying that this was for the citizens of South Carolina to decide. But months later, after losing South Carolina and the nomination McCain returned to the state and apologized for trimming on the issue. In an attempt to restore his reputation for candor, he said that he didn’t speak the truth of how he felt about the flag and what it symbolized: “I did not do so for one reason alone. I feared that if I answered honestly, I could not win the South Carolina primary. So I chose to compromise my principles. I broke my promise to always tell the truth.”

Sometimes McCain’s hot-headedness got in his way. That and his militaristic leanings. He came from a family of warriors and, but for his injuries from his captivity, he might well have remained in the Navy, following his father’s and grandfather’s career and becoming a top admiral. I was with him on Capitol Hill on the day after the September 11 attacks and his instinctive reaction was, “This is war!” War against whom was an unformed notion at that point. He then bought the line of the slimy Ahmed Chalabi, an exiled Iraqi politician who convinced leading Republican neocons that Saddam Hussein possessed nuclear weapons and that the U.S. should go to war against him, as it ultimately did in 2003. The resulting calamity in much of the Middle East is well known. Chalabi had dreams of becoming an Iraqi leader once Saddam was deposed, but nothing came of that; it turned out that despite his American boosters’ claims, Chalabi had little following.

Similarly, McCain backed the invasion of Afghanistan. Like others he overlooked that the British and the Russians had failed to tame the rugged, tribe-ridden country, and the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan is now in its 17th year. McCain continues to back the war, though he’s been frustrated with the Trump administration’s lack of a clear goal and policy there—which doesn’t differentiate it all that much from its predecessors.

The lowest point in McCain’s political life came not in connection with his campaigns but with his having been one of the “Keating Five”: five senators, four of them Democrats, who were accused of intervening in 1987 in the case of Charles Keating’s chairmanship of the Lincoln Savings and Loan Association, the management of which was being investigated by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. This was part of the savings and loan crisis spurred by the deregulation of such institutions in the early 1980s, which led to questionable acts by management, including investments in members of Congress in case their banks got in trouble. McCain, after expressing reluctance—so that Keating, a social acquaintance, an Arizonian, and a contributor to McCain, called him “a wimp” and the two men had a flaming row—attended one meeting between the senators and the regulators, but he said he was doing so as a constituent service and that the group should do nothing untoward. He did nothing further.

The Keating scandal later blew up and after a televised investigation—during which McCain, along with the four others, sat there like suspects in the dock—the Senate Ethics Committee found that two members of the group, McCain and Democratic Ohio Senator John Glenn, had done nothing wrong. But some Democrats argued that it wouldn’t do to have only Democrats charged in the case, and so Glenn and McCain were charged with using “poor judgment,” while the three other Democrats were reprimanded or charged with acting improperly. (Some retrospective accounts written in the 2000s said that McCain and Glenn were even included in the inquiry for the same political reasons: Democrats insisted that a Republican, McCain, be included and then angry Republicans argued that Glenn should be included.) The image was everything, and after that opponents tried to stain McCain, along with the others, with Keating, whose bank had gone under and who served time in prison for mismanagement of his company. McCain later wrote that attending that meeting was “the worst mistake of my life.”

Nevertheless, he was reelected to the Senate in 1992 and has been there ever since. In light of the financial industry scandals that followed, the Keating one was small potatoes, but it was a big deal at the time, and ever since, critics of McCain have tried to undermine his achieving the most important campaign finance law in our history by suggesting that he only got involved in the matter because of the Keating Five scandal.

McCain knew that the law would be chipped away at; he always saw campaign finance reform as “rolling reform.” A few years ago McCain checked out of the subject; he saw little hope for more reform in a far more partisan Senate and he had other subjects on his mind. But to McCain campaign finance reform was about something broader: He saw it as essential to restore the public’s faith in politics. Remember: This was in the early 2000s, before Supreme Court decisions undid large parts of McCain-Feingold, and before the inevitable success that, as McCain expected, of operatives finding ways to work around it. For McCain, the issue stood for the very idea of democratic government. I think it’s fair to say that the shredding of the law, along with ever more partisan redistricting, and successful efforts in numerous states to deprive minorities of their right to vote, have skewed our politics so that it no longer feels fair, flexible, workable. Money—the weight that the most wealthy now can throw into our elections and therefore the operations of government—remains the most important factor in the decline of our national life. This dismal situation doesn’t diminish the historic importance of the effort to reverse that decline, and the idea of campaign finance reform won’t die for a long time, if ever—just as Obamacare appeared to be teetering, but is shaping up to be a major issue in this year’s midterm elections.

McCain clearly has a strong element of the reformer in him, which fits with other aspects of his personality: the independence, the lack of baloney, the fierce determination to do right by his country as he had seen his father and grandfather do, and the importance of being seen as a straight shooter.

When George W. Bush signed the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform bill into law early on March 23, 2003, he was surrounded by the vice president and a few staff members, thus avoiding a public ceremony to which McCain would have to be invited. From Phoenix, McCain issued a one-sentence statement: “I’m pleased that President Bush has signed campaign finance reform into law.”

In looking back on that time, as McCain sought his big reform and dealt with numerous concurrent issues, and spoke of fighting hard but limiting his expectations, I found that I’d concluded, while writing my book, that John McCain was “a fatalist.” Undoubtedly, “the camps” had fed this streak in his nature. Without doubt it’s helping him now.