There’s one particularly famous scene in Fifty Shades of Grey. If you’ve read the erotic novel, published in 2011, you already know what I’m referring to: Christian Grey pulls a tampon out of Anastasia Steele’s body by string. Though perhaps the most talked about moment in the blockbuster book, it was left out of the film adaptation. “It was never even discussed,” director Sam Taylor-Johnson told Variety, for an article about how the film toned down the source material to avoid an NC-17 rating. The final cut had plenty of nudity, sex, bondage, and violence, but it did not have periods.

Though a monthly normalcy for around two billion people worldwide, menstruation rarely appears in American popular culture. When it does, as Lauren Rosewarne demonstrated in her 2012 book Periods in Pop Culture, it’s often treated as a source of embarrassment and shame, whether for comedic or dramatic purposes; sometimes it’s even a source of evil, as in the 1976 horror film Carrie. These depictions mirror, and likely influence, how Americans feel about menstruation. Because many men are squeamish about periods, and regard them as a sexual inconvenience, women are conditioned to avoid the subject—and to conceal their periods at all costs, lest they be seen bleeding. After all, visible periods have caused women to be censored by Instagram and possibly fired from work. The very fact of menstruation seems to appall the president.

There’s a product on the market, an alternative to tampons and pads, that promises a solution to the menstrual leaks that women have been taught to fear. The menstrual cup, which is made of flexible silicone, plastic, or latex and worn inside the vagina, collects blood instead of absorbing it, so it won’t get saturated. It can be worn for up to 12 hours, meaning fewer sprints to the bathroom. From the outside, it’s invisible; no string to peek out from your swimsuit. And since it lasts for years, it’s much more affordable and environmentally responsible.

But menstrual cups have largely failed to catch on, and some experts believe that’s due partially to the same stigma they’re supposed to help ease. Because menstrual cups, while they may help conceal periods to the outside world, they don’t allow women to conceal their periods from themselves. “Menstrual cups necessitate that women have more contact with their genitals and menstrual blood than they might be comfortable with,” Rosewarne told me.

At least with tampons, women can use long plastic applicators to insert them, and remove them with the tug of a string. But to insert a menstrual cup, users must push their fingers inside themselves, twisting the product until it fits right. Removing it requires even more skill. Users must then dump the cup out, rinse or wipe it off, and insert it again. Ew, many women think. Gross.

The menstrual cup and other reusable period products have the potential to do enormous good. Chief among that potential: Disrupting America’s $5.9 billion disposable feminine hygiene industry, whose products not only cost the average woman about $1,800 over her lifetime, but contribute greatly to the crisis of ocean plastics, as applicators and other used products turn up on beaches and in the stomachs of dead wildlife. But that industry has a cultural hold on American women, one that is perhaps just as powerful as the forces that keep women squeamish about themselves. At times, the two appear one and the same.

There are several barriers to widespread menstrual cup usage that have little to do with culture or industry. One is that they’re simply not for everybody. Though women are not supposed to feel a cup once it’s inserted, some have complained they’re uncomfortable to wear. Others say cups leak no matter how they finagle it. Some are concerned about having to wash it in a public bathroom (though you can just wipe if off in the stall if you want). And at around $20 to $40 a pop, they can be an expensive one-time purchase for low-income women. Free versions are available, but finding those requires time and effort. Plus shipping.

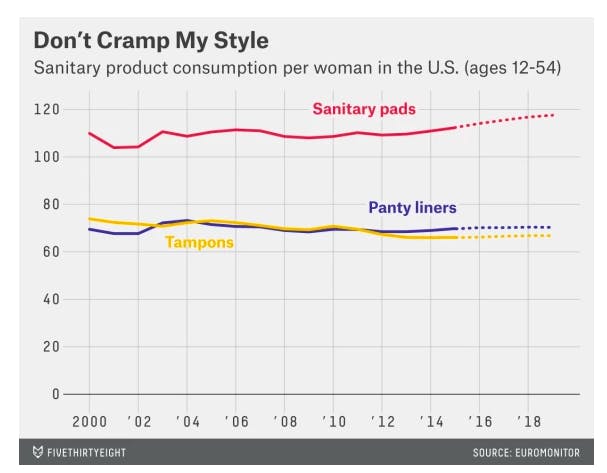

And then there’s the powerful force of habit. Even if a woman has no qualms about getting more intimate with her body, it’s burdensome to change how she manages her cycle—especially since most women have been managing it the same way every month since they were first handed a tampon or pad. Ninety-eight percent of American women use a combination of both products, though pads appear to be used most often.

Still, 70 percent of menstruating Americans use tampons at least sometimes, and the average woman here will use between 11,000 and 16,000 tampons in her lifetime, according to CNN. Many if not most of these women are not comfortable inserting them with their hands. According to Mother Jones, “More than 88 percent of the estimated $1.1 billion worth of tampons sold in 2015 had plastic applicators.” This distinctly American phenomenon—applicators are not widely used in Europe or Australia—can be traced to the start of the disposable feminine hygiene industry in the United States.

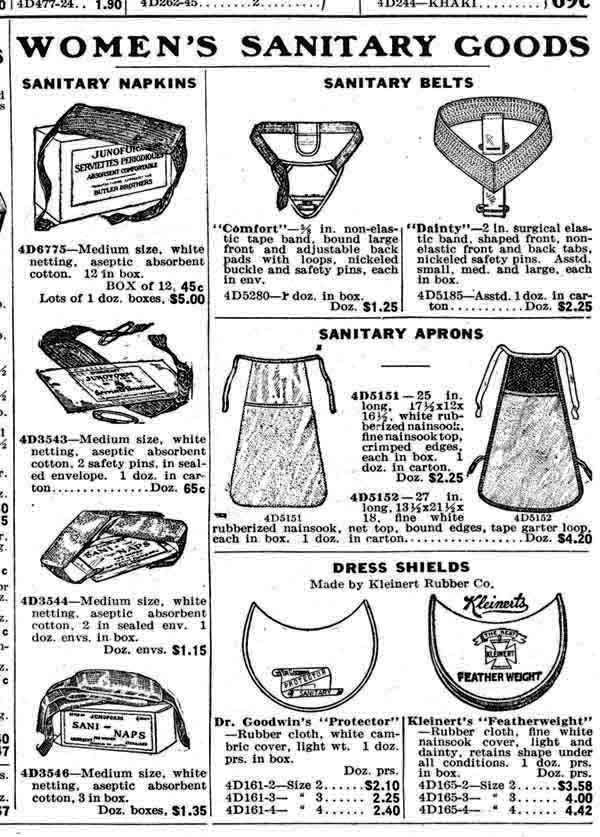

The modern tampon traces back to the mid-1930s, when Tampax began selling their patented applicator. This liberated American women, allowing them to move freely about the world, whereas previously their periods would have kept them isolated or uncomfortable for days (their options included sanitary belts, napkins, and aprons). But American society was, and in many ways still is, governed by puritanical notions of modesty and virginity. As Atlantic writer Ashley Fetters wrote in her definitive history of the tampon, many men feared that tampons might encourage “dreaded self-touching” among young girls and women—that they might even enjoy putting tampons in. The applicator was born.

Today, the plastic applicator is so prolific, it even has a nickname: Jersey beach whistles. “Plastic tampon applicators are unfortunately very common on our beaches,” said Ashley McCarthy of the non-profit Clean Ocean Action, which holds bi-annual cleanups of New Jersey beaches. Their last one removed 4,080 tampon applicators from 70 beaches, she said—an 18.88 percent increase from 2015. Across the ocean, vertebrate palaeontologist Darren Naish told me he’s “unable to stay on top of the amount of plastic crap” that piles up at his local nature reserve in southern England. “The plastic applicators are sometimes really abundant,” he said. “I made a point of collecting and counting them on one beach-clean, and in a 4-hour bout of collecting across about 30 meters of beach, I collected over 200.”

Naish said he also often finds bloodied pads during his beach cleanups, which makes sense because so many disposable period products are made from synthetic material that don’t efficiently biodegrade. (In America, tampon and pad manufacturers are not required to list their ingredients.) This means that much of the 250 to 300 pounds of “pads, plugs, and applicators” the average woman disposes of every year (or 62,415 pounds over her lifetime) ends up in landfills—or worse, the sewer. Those flushed products can make their way to the ocean, breaking down into tiny microplastics, which kill wildlife and have been found in 90 percent of bottled water.

Disposable products, once viewed as a symbol of America’s prosperity, are steadily losing favor. We’re witnessing the decline of plastic bags, plastic straws, foam cups; the rise of reusable water bottles and totes.

The moment seems ripe for a boom in menstrual cups, and there are signs they’re becoming more popular. According to the market research firm ReportLinker, the global market for menstrual cups was valued at $995 million in 2016, and is expected to reach $1.4 billion by 2023. Then again, the global tampon market is growing at a faster rate, expected to reach $6.3 billion by 2025. About $4.6 billion of that is expected to come from the applicator segment.

The very reason applicators are popular in the U.S. may be the same reason the menstrual cup market struggles. “There are certain conservative societies in various countries, where the level of acceptance of [menstrual cups] is very limited, which could hinder the market growth,” according to ReportLinker. Indeed, researchers have encountered these attitudes when trying to bring menstrual cups to women in poor countries, where limited access to hygiene products has been shown to be “a barrier to occupational attendance and engagement.” One study showed that factory workers in Pakistan “missed up to three days’ work per month due to menstruation.”

Thus, North America is currently the leading contributor to the menstrual cup market, and is expected to retain this position for several years due to “greater awareness” of the benefits. Those not only include saving money—a $30 cup can apparently last up to 10 years, though most users report two to four years—but a decrease in general annoyance with one’s period. Citing a 2011 clinical trial of menstrual cups, the magazine Pacific Standard noted that regular tampon users reported “feeling more satisfied with menstrual cups than their usual means of menstrual management.” Ninety-one percent of those who tried cups said they would recommend them to friends. And friendship recommendations can be powerful: In 2010, researchers found that women in Nepal became 18.6 percent more likely to use cups if their friends were using them.

“Women’s bodies—including their menstruation—have long been used as a justification for their subordination in our society,” Rosewarne told me, as we discussed pop culture’s negative portrayal of periods. But women can counter this by sharing their positive experiences with their periods. So allow me: I think periods are interesting and healthy, not gross, and if you can’t tell already, I’m a big fan of menstrual cups. I like that I’m not polluting the oceans. I like that I’m now saving about $50 a year. And I like how it brings me closer to my body. If more women in America were willing to talk about these things, there wouldn’t just be less plastic in the ocean and more money in our pockets. We could change how society views menstruation, saving women a lot of unnecessary grief. If we’re really lucky, maybe the next Fifty Shades movie will have a racy scene featuring a menstrual cup.