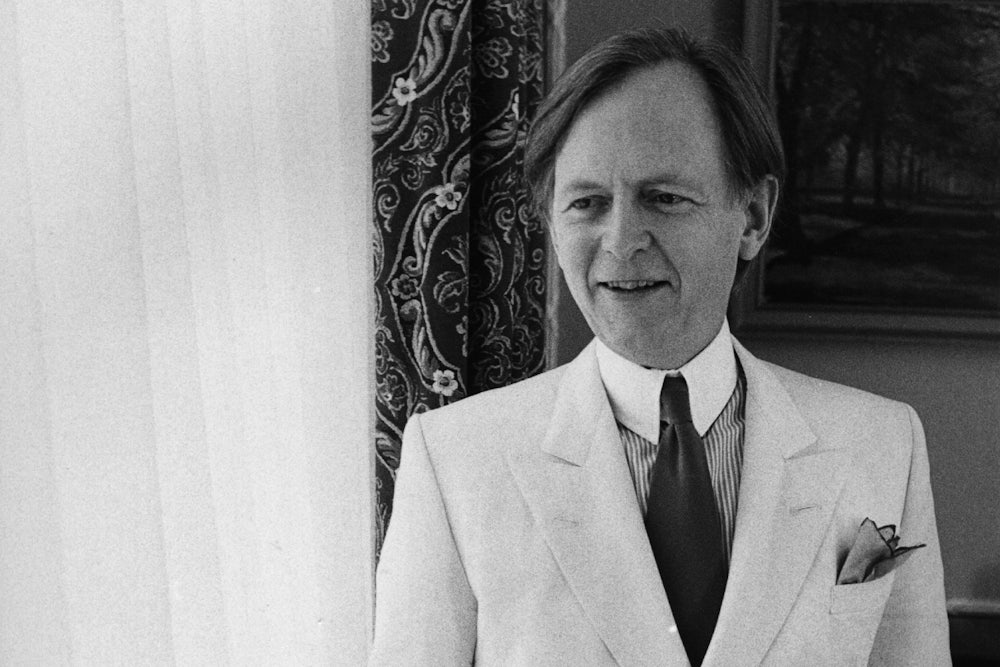

Wolfe, who died Monday at age 88, was known as a dandified doyen of the New Journalism, a reporter who embedded with hippies and race car drivers and astronauts, and later as a grandiose novelist. But Wolfe began his career as a scholar. In 1956, he completed a doctorate in American studies at Yale, writing a thesis titled The League of American Writers: Communist Organizational Activity Among American Writers, 1929–1942. The most obscure of Wolfe’s many works, it is also the key to his entire oeuvre.

Although he was politically conservative, Wolfe wrote in his these with great sympathy about proletarian novelists of the 1930s such as James T. Farrell and John Steinbeck, whose work brought the grit of reality to fiction writing. Wolfe came to see these writers as part of a larger tradition of journalistic literature stretching from Daniel Defoe to Charles Dickens to Emile Zola. But something had gone wrong, Wolfe felt, in the twentieth century, when literature and journalism diverged. Literary fiction, under the sign of modernism, became too obsessed with experimentation and wordplay, while journalism, under the imperative of objectivity, adopted an arid view from nowhere.

Wolfe’s great mission in life was to remarry literature with journalism. He first did so as a pioneering journalist, writing about the cultural chaos of the 1960s with immersive, bracing prose. In 1968’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, he described a busload of hippies reacting to a forest fire: “By this time, everybody is off the bus rolling in the brown grass by the shoulder, laughing, giggling, yahooing, zonked to the skies on acid, because, mon, the woods are burning, the whole world is on fire.” Wolfe was no hippy but lived among them, absorbed their language, and told their story in their voice. He did that with all his subjects, whether it was Marshall McLuhan or jet pilots.

Later, with less success, Wolfe tried to flip the equation by writing novels based on extensive research. The first of those books, 1987’s Bonfire of the Vanities, a memorable portrait of Manhattan decadence, was a great success. But subsequent novels tended to be bloated and revealed the limitations of his empathy. His best work remains the journalism he did in the 1960s and 1970s, such The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, The Pump House Gang, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, and The Right Stuff. They are not just classics of journalism, but included in the canon of American literature.