In 2012, the artist Adrian Piper made an announcement. The news was posted on her archive’s web site, with a cheerful portrait of her, head tilted, eyes warm and open, smiling. The photo would look like an ordinary head shot if it were not for the unnatural coloring—Piper’s hairline is orange, and her skin is an eggplant shade of purple. At the bottom, she included a note:

Dear Friends,

For my 64th birthday, I have decided to change my racial and nationality designations. Henceforth, my new racial designation will be neither black nor white but rather 6.25% grey, honoring my 1/16th African heritage. And my new nationality designation will be not African American but rather Anglo- German American, reflecting my preponderantly English and German ancestry. Please join me in celebrating this exciting new adventure in pointless administrative precision and futile institutional control!

She signed and dated it below.

On first reading, this announcement—which as an artwork is titled Thwarted Projects, Dashed Hopes, A Moment of Embarrassment—appears absurd: A person can’t retire their official identity and endow themselves with a new one simply by writing a note; Piper points to the futility of such an endeavor in her last line. But, like so much of her work, Thwarted Projects throws a challenge to the viewer: What new and liberating possibilities might appear if we took this conceptual exercise seriously?

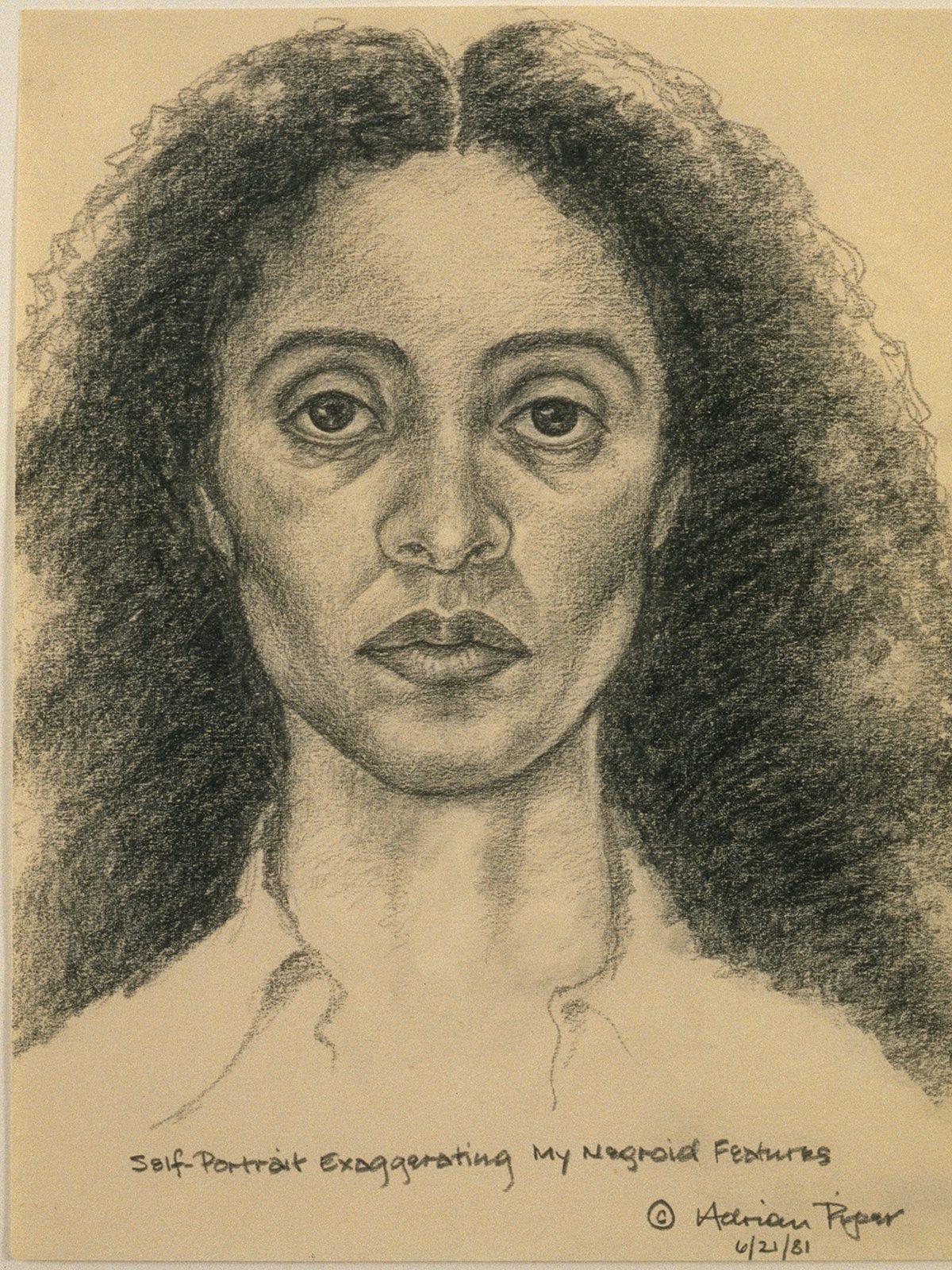

Piper has spent decades making art about identity and working through questions of perception as a philosopher. She is perhaps best known for a pair of calling cards she produced in the late 1980s to give to people who made racist remarks in front of her or tried to pick her up. “Dear Friend,” they both begin, before informing the recipient: “I am black or I am here alone because I want to be here, ALONE.” For years, white art critics dismissed or chastised her work, uncomfortable with this type of confrontation and the demands it placed upon them. In a 2001 review in Art in America, Eleanor Heartney took issue with Piper’s treatment of whiteness as “an undifferentiated state of being” and went on to ask if the artist considered Asians white. In 2000, the New York Times critic Ken Johnson wrote, “The big question is, does Ms. Piper’s hectoring, often bitterly sarcastic approach actually work?”

Ironically, such reactions show how effective Piper’s art is at pushing people out of their comfort zones. A new retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016, demonstrates how expertly she’s deconstructed the categories we use to classify ourselves and is instructive at a time of intense debate over how ideas of identity shape American politics. The exhibition, curated by Christophe Cherix, Cornelia Butler, David Platzker, and Tessa Ferreyros, spans Piper’s entire career and occupies the museum’s entire sixth floor—the first time MoMA has devoted the whole of this space to a living artist. It’s an artistic and emotional journey, and despite a lot of aesthetic variation, it follows a clear path, from introspection to enlightenment.

Piper began making art when she was a teenager, attending the Art Students’ League while she was in high school and enrolling in the School of Visual Arts in New York City in 1966. The earliest works in the show date from this period: colorful, psychedelic renderings of fractured figures and a series called The Barbie Doll Drawings (1967), in which images of dolls are de- and reconstructed with a grotesque glee. But Piper quickly joined the avant-garde of her time, leaving figuration behind for the conceptualism then being formulated by Sol LeWitt and other (mostly male) artists.

The breakthrough of conceptual art was to privilege the idea driving a work over its physical form. To that end, Piper’s pieces from this period investigate how we understand time and space, as well as how viewers interact with art. She produced texts that described and delineated space—“This square should be read as a whole; or, these two vertical rectangles should be read from left to right or right to left,” begins Concrete Infinity 6-Inch Square (1968)—and took out an ad in The Village Voice, stating: “The area described by the periphery of this ad has been relocated from Sheridan Square New York, N.Y. to (your address).” For Context #7 (1970), she asked visitors to a MoMA show to respond on paper to “this situation (this statement, the blank notebook and pen, the museum context, your immediate state of mind, etc.)” and collected the replies in binders.

In the present MoMA exhibition, the galleries containing these rigorous, abstract works feel like a laboratory in which Piper is testing hypotheses about art and perception. But beginning in 1970, the “outside world,” in her words, impinged upon her “aesthetic isolation”: The invasion of Cambodia, the Women’s Movement, and the National Guard and police killings at Kent State and Jackson State all affected her, as did the closure of the City College of New York for two weeks by black and Puerto Rican students demanding more accessibility and diversity at the school. (Piper had just started pursuing her bachelor’s in philosophy at CCNY; she went on to get a Ph.D. in the subject at Harvard and to teach it at several universities, including Wellesley College, where she became the first tenured African American woman in the field.)

Also around this time, Piper started to encounter surprise— and often disdain—from members of the art scene when they realized that she was not a white man, as they’d assumed, but a black woman. “I can no longer see discrete forms or objects in art as viable reflections or expressions of what seems to me to be going on in this society,” she wrote in 1971. “They refer back to conditions of separateness, order, exclusivity, and the stability of easily accepted functional identities that no longer exist”—if they ever did. Piper’s solution was to turn her body into the form or object instead, to make herself a situation with which the viewer would have to contend.

In 1970, she began doing weird things in public: She rode the bus with a towel stuffed in her mouth. She filled a purse with ketchup and then, in the bathroom at Macy’s, dug through it to find a comb. She memorized Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and danced to it silently. These works, collectively titled the Catalysis series, focused on the relationship between art and viewer in a new, more immediate way; Piper wanted her art to be a “catalytic agent” that would spark a change in the people who encountered it.

The common factor in the Catalysis works was Piper’s appearance as a generalized oddball or outcast (for Catalysis I, she soaked her clothes in vinegar, eggs, and cod-liver oil for a week and then wore them on the D train at rush hour). But in 1973 she began testing what would happen if she introduced into the public a far more specific identity, one to which people had already attached preconceived ideas and stereotypes. The Mythic Being, as she called her character, was a man with a mustache and an Afro who wore jeans and mirrored sunglasses. He saw films at Lincoln Center and cruised white women, all the while reciting mantras that were lines from Piper’s diaries.

Piper also placed the Mythic Being in ads she took out in The Village Voice and in static, two-dimensional artworks, both formats accentuating the contrast between image and text. In some of the former, the Mythic Being appears inscrutable alongside thought bubbles filled with teenage lines about liking boys at school. In the latter, Piper uses more theoretical language (including text pulled from Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, which she’d begun studying in 1971), undercutting the assumptions that a largely white and affluent art-viewing public might make about the intelligence of a young, hip-looking man of color with an Afro. “Piper believes that speech claims attention,” Hilton Als wrote in Artforum in 1991, “and that through attention, one can proceed to the idea of instituting change.”

Pairing images and words would become a crux of Piper’s practice from the 1970s on, as she learned to use the juxtaposition between them to create uncertainty. Often this takes the form of photo-and-text combinations: The Pretend series (1990), for example, features repurposed images, many of black people, accompanied by the typewritten phrase: “Pretend not to know what you know.” The directness of the address here offsets the vagueness of the statement: Clearly, each of us has a “what” that we’re avoiding in relation to the photos. Piper prompts us to do the work of identifying it.

Alongside her use of direct address, she began to anticipate her audience’s reactions. One of the first works to do so was Art for the Art World Surface Pattern (1976), a small, freestanding room wallpapered with photos of violence and destruction, over which is stenciled the phrase: not a performance. As you stand inside and contemplate the images, an audio track sounds out the inner monologue of an imaginary, annoyed viewer, voiced by Piper. “Oh, I get it, this is social conscience art,” the voice says. “Jesus, is this stuff supposed to be expanding my consciousness?”

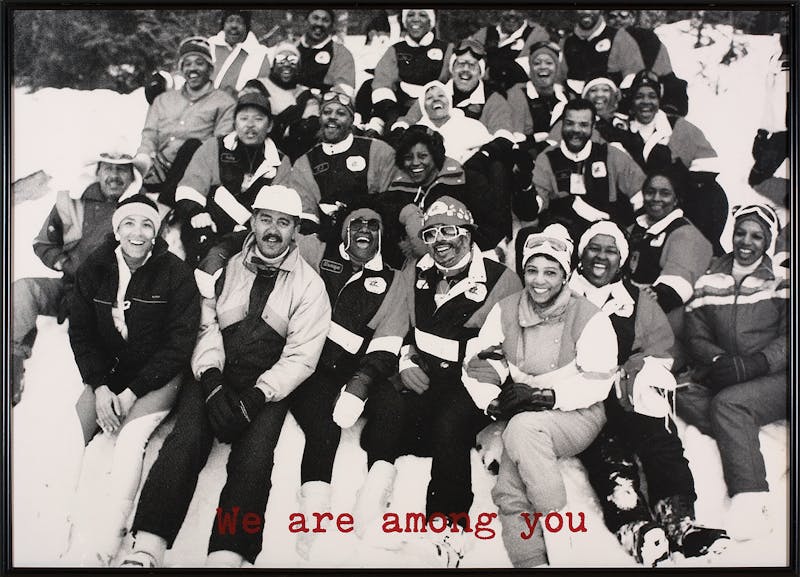

The retrospective is filled with such voices. They are often shades of the ignorant, defensive white person who’s liberal enough to go see the art but doesn’t like the way it makes her feel. “I feel attacked by this piece, where I don’t feel attacked by blacks at all,” protests one of the speakers in Four Intruders Plus Alarm Systems (1980). The piece presents another freestanding room, this time with four large, illuminated photographs of black men inside, each paired with a set of headphones. As you enter the structure alone, you confront the men’s faces and glowing eyes, then listen to imagined viewers’ reactions that suggest how deeply embedded stereotypes of black male criminality are. In another piece, titled Safe #1–4 (1990), images of smiling black people fill the corners of a small room, accompanied by reassuring texts (“We are among you; you are safe”). Meanwhile, a woman’s voice says: “My housekeeper and I have a wonderful relationship. She’s literally my best friend,” but “I don’t like being guilt- tripped.... Subtle ambiguity, a certain je ne sais pas quoi is so much more effective.”

“Subtle ambiguity,” of course, allows white people to evade a reckoning with their own identities—a privilege not often afforded those who aren’t considered white. One of the most affecting pieces in the show drives this point home. Located by itself in the museum’s atrium, What It’s Like, What It Is #3 (1991) is constructed to look like a minimalist cube whose whiteness is glaring and harsh. Tiered benches are built into the sides of the space, at the center of which stands a white, rectangular column holding four screens. The head of a black man appears on the screens; facing one direction at a time, he rebuts a list of qualities stereotypically assigned to him: “I am not vulgar,” he says. “I am not scary.... I am not stupid.” His eyelids flutter as he articulates each line carefully; you can sense exasperation and frustration under the surface, but he doesn’t allow them to bubble up.

The man’s recitation evokes incredible pathos, but Piper doesn’t let the viewer wallow in sympathy. By placing the man in the center of the room—a room she compares to an amphitheater “of the sort that one would sit in to watch Christians being devoured by the lions”—she makes him a spectacle. What It’s Like, What It Is #3 brilliantly renders the way that white supremacy forces black people to perform their humanity. And as onlookers, we are complicit.

This kind of fraught intimacy is one of Piper’s hallmarks. But what the MoMA retrospective lays out clearly is her ability to deploy it across different emotional registers. Because she was stereotyped for years as an angry black woman, the humor and levity in Piper’s art went underdiscussed. From those satirical voices throughout the show to The Humming Room (2012), which requires anyone who steps into its space to hum, Piper’s sometimes confrontational style has always been balanced by a more inviting, playful one.

In one of her most famous pieces, Funk Lessons (1983–84), Piper invited people of all races to attend events where she taught them some of the history and dance moves of funk. A clip from a video based on one of these performances plays at MoMA. It shows people—many of them white—looking both relaxed and slightly ridiculous as they practice nodding their heads and clapping or just let loose and freestyle. Piper knew that white people’s fears of black people were often bound up in their misapprehension of black culture: Funk Lessons was a way to alleviate that fear. By making a certain type of black culture accessible, she created a social contract, thereby “transferring agency from artist to participant,” as Cornelia Butler writes in the exhibition catalog. She encouraged participants to take on “the obligations and responsibilities of nothing less than enlightenment.”

This is, arguably, the heart of Piper’s practice: the transferring of agency—of obligations and responsibilities—from her to us. She does it in all sorts of ways: by getting us to react, by asking us to dance, by impelling us to consider our place in a racial hierarchy, by prompting us to reflect. Her artworks are not, as some critics would have it, castigating lectures but an ongoing request for our participation.

The retrospective is capped off by one of Piper’s most recent works, The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1–3 (2013). To participate, viewers walk up to a sleek, curved, gold and black desk and sign a contract promising one (or all) of three things: “I will always be too expensive to buy.” “I will always mean what I say.” “I will always do what I say I am going to do.” These statements feel basically impossible to agree to—which, of course, is the point. The work invites us to commit to the challenge of maintaining personal integrity; Piper’s creation of it is an act of faith. It may seem like she’s setting us up to fail, but I suspect she wants very much for us to succeed.