When the early returns of the November 26 presidential election in Honduras began coming in, supporters of the leftist opposition candidate, Salvador Nasralla, had cause to celebrate. With 57 percent of polling stations counted, he had a five-point lead, a seemingly irreversible advantage. But then the vote-counting system went dark, victim of a computer glitch. A day and a half later, the system began working again, only now the conservative incumbent, Juan Orlando Hernández, had suspiciously caught up, and soon after, he took the lead. Cities throughout the country erupted in protest, and military police responded with force, firing at demonstrators. After three weeks of turmoil, electoral officials finally declared Hernández the winner; by the time he began his second term, on January 27, more than 30 people had been killed.

Media in the United States and other countries seemed hardly to have noticed. Perhaps it’s because Honduras is small and poor, with a population of nine million, little oil, and no Islamist radicals. Or perhaps it’s because stories of rigged elections and crackdowns on protesters have become a global commonplace.

Liberal democracy seems to be on the retreat in Eastern Europe and Asia, with countries such as Russia, Hungary, Turkey, and the Philippines often cited for their turns toward authoritarianism. But Latin America, a region of more than 600 million people, is suffering its own retrenchment. A rocky few years of disputed court rulings, mass protests, and violent crackdowns from Central America to Brazil have brought democratic rule in the region to its lowest point so far this century. Which is why what happened in Honduras is worth thinking about: It offers insights into the broader problems of liberal democracy everywhere.

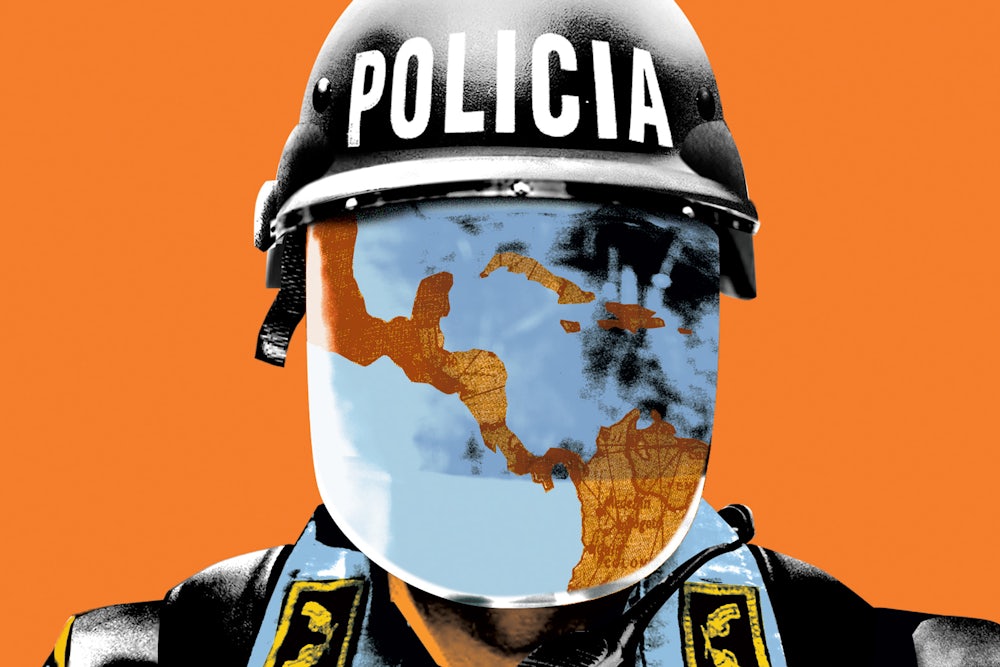

In Latin America, the new generation of strongmen come from both the political left and right. They include the pro-Washington Hernández, who has promised to rid Honduras of the gang members in its slums; and, in Venezuela, the anti-gringo Nicolas Maduro, who claims he is carrying forward Hugo Chavez’s revolution against the oligarchs who hoarded the nation’s oil wealth. But what unites these disparate personalities is a shared history. Decades of elections and open markets haven’t done what they were supposed to do: level the region’s financial and social inequality and bring an end to violence. Many Latin American countries have actually become more violent since they transitioned to democracy in the 1980s and ’90s. The shortcomings of democracy are allowing a new generation of authoritarian leaders to rise in Latin America.

In the late 1970s, during the Cold War, authoritarian governments ruled most of Latin America. Mustachioed generals hunkered down in presidential palaces, while the U.S. government backed dictators and military juntas it believed were bulwarks against communism. American troops used Honduras to train Contra rebels to fight the leftist Sandinistas in neighboring Nicaragua. Likewise, Fidel Castro’s Communist Cuba imposed its own form of Latin dictatorship, while Mexico was in the grip of one-party rule by the ideologically nebulous Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

As the Cold War wound to an end, however, the dictatorships fell, and the caudillo generals retreated into the historical shadows. From 1980 to 1989, Peru, Honduras, El Salvador, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Chile, and Guatemala all returned to civilian rule. In 2000, when Mexico elected its first non-PRI president in seven decades, the complete transition to democracy throughout the region looked inevitable. Only Cuba resisted genuine multiparty elections, and many predicted this would end when Castro finally died. Latin America seemed to be a case study in how democracy could lay down strong roots and prosper.

What also prospered was the idea that democracy and free markets were the key to improving people’s lives. International organizations pushed to ensure credible elections, sending observers to Latin American capitals. The World Trade Organization labored for free markets and lower tariffs, filling stores with American laptops, German cars, and Chinese-made clothes.

But little effort was made to establish an effective rule of law. Police who had tortured and killed under military dictators carried on using the same techniques in the new era. Prosecutors solved cases for those who would bribe them rather than defending the poor. And black markets mushroomed, not only for drugs and guns, but wildcat gold mining, pirated movies, and stolen oil. While most of the world grew safer, Latin America did not, with murders across the region going up 11 percent between 2000 and 2010. In total, there were more than a million homicides in that decade.

This violence has shattered foundational elements of democratic life. Mexico’s so-called drug war is estimated to have killed 119,000 people in a decade, destroying communities and forcing people from their homes. Assailants have murdered more than 100 Mexican journalists since 2000, while 30,000 people have disappeared altogether. Silencing reporters and disappearing people were the hallmarks of Latin America’s military dictators. These things are still occurring today, but they are even more pervasive, thanks to the crime cartels.

In the northern triangle of Central America, which incorporates Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, the violence per capita has had a cascading effect. The Mara gangs, who use murder as a tool to elevate their status within cliques and to shake down businesses, are strangling the local economy, a key factor driving the large-scale emigration of Central Americans to the United States, especially teenagers, whom the gangs target as both victims and recruits. Latin America’s strongmen have also used the criminal violence as a means to justify authoritarian political measures. Honduras’s Hernández first won power on a law-and-order platform in 2013, when the country had the highest murder rate in the world. He poured money into a new military police force, which was of course loyal to him. It cracked down on gang members and reduced the murder rate. Yet it was this same police force that would later shoot marchers protesting Hernández’s reelection.

In neighboring Nicaragua, President Daniel Ortega, a former Sandinista guerrilla, has resisted the spread of gangs with the help of networks of community volunteers (and government spies) originally created to stop the infiltration of Contra rebels in the 1980s. Ortega, like Hernández, has used the threat of gang violence as a pretext to increase police powers. Meanwhile, a Nicaraguan court decimated the political opposition by ordering the removal of 16 of its lawmakers from the country’s Congress, and Ortega abolished term limits in 2014, winning his third consecutive term in 2016, with his wife serving as vice president. In April, his police fired on protesters, and there were dozens of deaths in scenes that looked eerily similar to Honduras a few months earlier.

In Brazil, the former military officer Jair Bolsonaro is campaigning for the presidency by calling for his own hardline anti-gang policy, including arming citizens to shoot criminals. At his rallies, he reminisces about the good old days of lower levels of violence under military dictatorship. His rise comes after the controversial 2016 impeachment of the leftist President Dilma Rousseff, which many view as a soft coup, and the April jailing of Rousseff’s mentor, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who wants to run for office again. President Michel Temer, who took office in August 2016, after Dilma was impeached, has been accused of corruption. In an indication of his tendencies, Temer sent the military to take control of public security in Rio de Janeiro state in February.

Latin America, it should be said, is still less authoritarian than parts of Asia and Africa. Chile and Argentina, home to some of the most notorious dictators of the last century, have allowed power to pass successfully back and forth between elected presidents from the left and right. Costa Rica is hailed as a vanguard of democratic environmentalism. These countries have kept crime lower without resorting to authoritarianism, using a mix of more professional (if still far from perfect) policing and relatively effective social programs. Ecuador has seen lower crime rates after reducing poverty.

But despite improvements by some governments, Latin America remains the most unequal region in the world, with 10 percent of the population holding roughly 71 percent of the wealth. Sprawling slums without paved roads and running water provide a steady stream of recruits into the crime armies. There are no simple solutions to these problems. But one thing that could be done is to recognize that elections and freer markets will not, on their own, improve people’s lives—governments are going to have to do more. First, they can build police forces that will genuinely defend people from predatory criminals while not being used as a tool of repression. And next, they can channel government resources into poor communities that need them most, rather than their own pockets. Democracy means a lot more to people if it translates into tangible benefits—it is then, and only then, that people become willing to risk their lives defending it. Politicians who talk about democratic values but don’t offer concrete answers to what matters most leave a vacuum for authoritarian leaders who do.