When Frederick Seidel reviewed Rachel Kushner’s second novel, The Flamethrowers, in 2013, he found the book “tiresome, histrionic, hysterically overwritten, desperate to show how brilliant it is,” and full of “yawningly long bravura description.” Kushner’s portrait of her heroine, Reno, as a stylish motorcyclist was, Seidel felt, too much: “The novel too often sounds like the stylized voice-over narration of film noir, sardonic, self-conscious, very American, the sound of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity.” He concluded with the withering charge that Kushner wrote a book that is interested in becoming a movie.

That accusation implies that Kushner’s novels are not subtle character studies the way that, say, a Paul Auster or John Banville novel is. Instead they are bright and bold and populous. Both The Flamethrowers and her first novel, Telex From Cuba, teem with historical research and hypervivid detail. Throwing its protagonists into the maelstrom of 1950s Cuba, her debut was split between sugarcane plantations in Oriente Province and political agitation in Havana: A French man sells weapons to the highest bidder and tangles with a mysterious zazou dancer named Rachel K., while across the country, two children grow up in the colonial world of the virgin banana daiquiri and Xavier Cugat at the Cabaret Tokio. The Flamethrowers tracks Reno through the “buoyant swells” of the ’70s New York art scene, where Gansevoort Street ends in an “old pier building of corrugated metal.” Reno flees one set of arrogant men for another. Once in Italy she transforms from mere girlfriend into a fly on the wall of a cell of agitators, and witnesses carabinieri in “black gauntlet gloves” punching people in the wet streets of Rome.

Rather than beginning with a character’s psychology, Kushner has tended to take up great historical arcs and weigh their meaning, to feel the pressure that world events exert on the minds that live through them. Reno and Rachel K. do make individual choices. But those choices vibrate in tension with their global political contexts. In both novels, Kushner cuts the glamor of Rome, New York City, and Havana with scenes of subaltern life at the edge of manufacturing. Momentous upheavals can equally sweep a person toward thrilling self-realizations or grind them into rage or despair, her novels make clear, although she has tended to cast glittering white women at the front and center of her narratives.

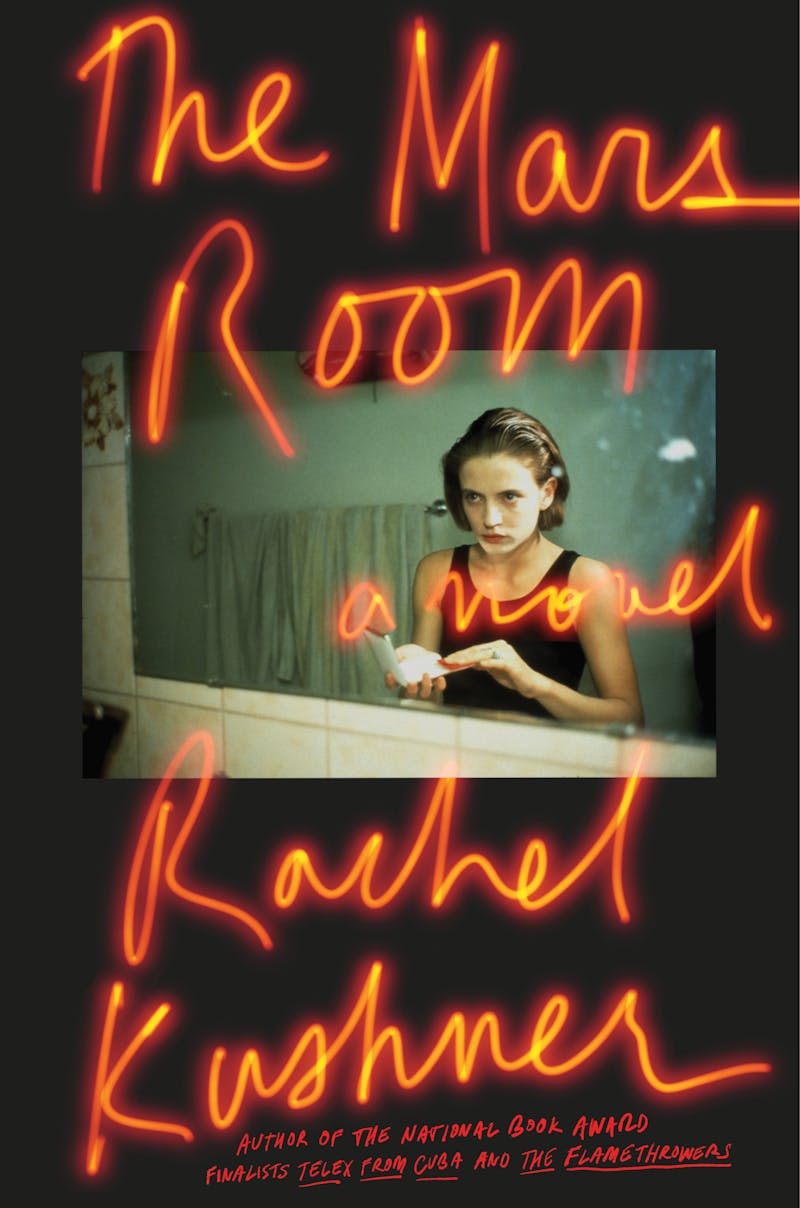

Kushner’s latest book, The Mars Room, marks a change in that respect. A prison novel, set in a closed system, it may seem a departure for a writer so focused on broad currents, cultural and national umwelts. Just beginning a very long stretch on the inside, the protagonist, Romy Hall, is physically confined and cannot see very far ahead. “I don’t plan on living a long life,” she tells us. “Or a short life, necessarily. I have no plans at all. The thing is you keep existing whether you have a plan to do so or not, until you don’t exist, and then your plans are meaningless.” She spends a lot of her time looking back, dredging up an unmoored adolescence in San Francisco, where she ran around doing drugs and being bad with her friends, then checked out books from the library and stripped for work.

Romy slipped and skidded into committing the kind of crime that cancels out a person’s future. She chose her job at the strip club—the titular Mars Room—because she “did not have to show up on time, or smile, or obey any rules, or think of most men as anything other than losers to be exploited.” But “something brewed” in her over those years, as she took extra shifts instead of hanging out with her son on Thanksgiving. A customer started to believe that they had a real relationship. He followed her, stalked her. “This thing in me brewed and foamed,” Romy says. “And when I directed it—a decision that was never made; instead, instincts took over—that was it.” Kushner formulates Romy’s crime—the barely-named act that has stolen her freedom—not as an act of resistance against a cruel world but as the result of a force she could hardly recognize as her own.

What interests Kushner, much more than the crime itself or its psychology, are the systems that Romy comes up against. Growing up poor, she makes decisions that she knows a better-cared-for person wouldn’t make. “You would not have gone,” she addresses the reader. “I understand that. You would not have gone up to his room. You would not have asked him for help. You would not have been wandering lost at midnight at age eleven.” The absent mother begets the midnight wandering, which begets the eleven-year-old Romy going to a stranger’s home, which begets the “thing in me” that lands her in prison.

Incarceration is the system Kushner captures most vividly and unsparingly. The story is split mostly between Romy and a teacher named Gordon Hauser. He’s wary of the prisoners but charmed uniquely by her: Kushner lets him come and go, in and out of the system, which helps her paint its boundaries. Sometimes other prisoners take over the narration, including a corrupt cop named Doc. In strange interstitial chapters, Kushner also includes short excerpts from the diary of Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, which Gordon is reading. Describing life inside the prison, Kushner builds up a pointillist image of the control the authorities exert. “Holding hands is sustained contact and not tolerated,” Romy learns; crying and high fives and laughing are either discouraged or forbidden outright.

Romy observes a “red wedge” painted onto the clocks in the prison to mark five minutes before and after the hour, for women who cannot tell the time. The red wedge is for “the imbecile.” Romy does not think that clock illiteracy itself is imbecilic: “Plenty I have met in prison cannot read, and some cannot tell time,” she says. But no woman she has met in prison is stupid, Romy clarifies. “The imbecile the rules and signs are meant to address is nowhere to be found.” Despite this, everything in prison, Romy writes, “is addressed to the woman for whom the red wedge is painted on the clock face.”

This is not the glamorous world of ’70s New York City, but it is just as sharply rendered. The difference in this case is that Romy has no way of escaping the system inside which she lives. At a time when there are over two million people in prison in America, the novel’s vibrancy—its insistence on recognizing the pulsing humanity of the inmates—cannot be, as Seidel thought The Flamethrowers was, too much. The history of Cuban sugarcane and Italian workers’ struggles are both important to our world, no doubt. But mass incarceration in the United States is happening here and now.

“For the conservative,” Kushner told The New Yorker in February, “the criminal is ‘bad.’ For the liberal, the criminal is remade to seem relatively innocent, so that the liberal can feel ‘empathy.’ ” Those categories are not for the novelist. Both liberals and conservatives see crime in a way that excludes “the larger truth of the organization of society: that some very poor people are destined to commit crimes.” For Romy, violent crime is not a Dostoyevskian drama of individual ethics. She and the poor women imprisoned along with her have been lumped together, watching the red-wedge clock, because their circumstances nudged them into behaviors deemed criminal.

That is not to say Romy has no agency. She defines herself through motherhood and memory. While incarcerated, she holds on to the thought of her son, Jackson. He “believed in the world,” she recalls. “I searched his face with my closed eyes. Felt the dewy touch of his hand in my hand. I heard his voice, felt the warmth of his body when he wrapped his arms around my waist.” Just as Reno felt time warp and shift as she hurtled across the salt flats, Romy focuses in her cell “on the grain of Jackson, the sensation of him. Nothing they did could touch that grain. Only I could touch it, touch it and stay close.”

It’s an old idea, that the jailer cannot take the inner life away from the incarcerated person. “I lay in my tiny bare cell and tried to see Jackson, to visit with him,” Romy says. She thinks back to the way the little boy wanted her to know what he was studying, and how he tested her on styles of columns in a coloring book. “If there were a bunch of designs at the top, I knew to guess, ‘Corinthian.’ ” Kushner has set up a character inside a closed system, hemmed in by systems all her life, almost in order to show with clarity that touch, love, mothering, memory can never be fully constrained.

“In his essay celebrating the wonder of wild apples, Thoreau concedes they only taste good out of doors,” Kushner writes. The experience of interiority and the outside conditions controlling our bodies are bound up in a way that only imprisonment unites so literally. Romy gets outside, for a while. She hears an animal cry and is afraid. In its shriek, Romy senses the absolute difference between being locked up and being free. “Its cry was almost human, but in the almost human manner of an animal in the wild.”