It was neither the best nor the worst of times. But in contrast to the relative placidity of the 1950s, the events of 1968 opened up previously unimaginable vistas to people all across the globe. “We knew about the Paris commune,” the surrealist artist Jean-Jacques Lebel tells Mitchell Abidor in May Made Me, a new collection of oral histories of that year. “This was going to happen again” in May 1968, he had felt. “So you could have the near orgasmic joy of taking part in something much greater than yourself.” The protests began with calls for an end to same-sex dormitories at French universities and quickly developed into a general strike involving some 10 million workers from every segment of French society. By the end of that year, students and, to a lesser degree, workers in nearly every part of the world would rise up.

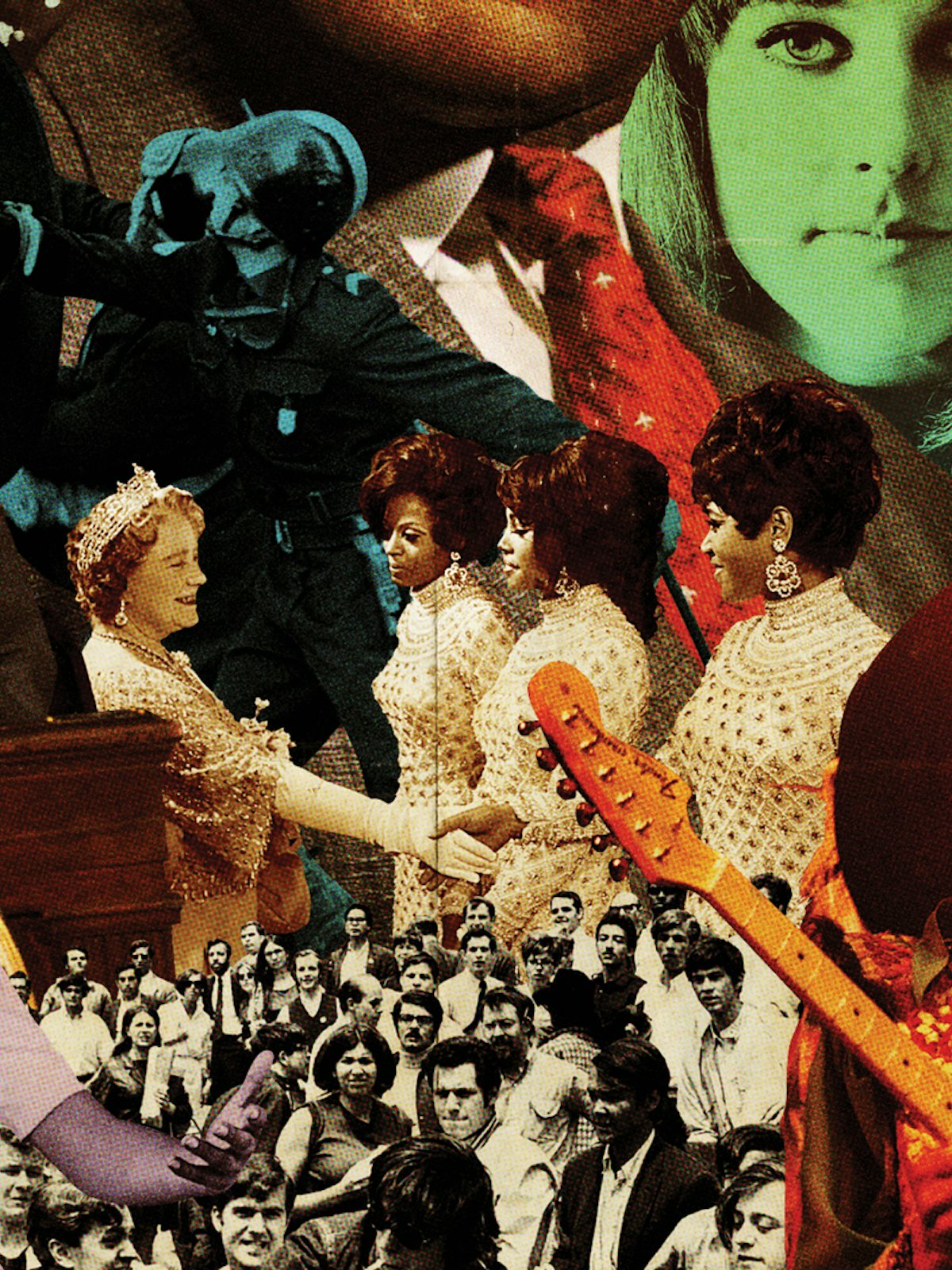

The spirit of 1968 was not merely political. Simultaneously individualist and collectivist, as well as both sober and psychedelic, it was cultural, economic, sexual, hedonistic, spiritual, and transcendental. In a few of its more crucial aspects, it was a wild success. Two 68ers—Jack Straw in Britain and Joschka Fischer in Germany—became foreign secretaries of their countries. The women’s movement, galvanized in large part by the unrelenting male chauvinism of 1968’s leaders, intervened in history, as did movements for racial and ethnic equality. Protests against the war in Vietnam played a role, however indirectly, in ending it. Soviet-style communism did, eventually, topple. Universities were transformed, as was, for a brief moment in time, the Catholic Church. Conscription ended. Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix changed music.

But a powerful reaction began as early as the first protests in Paris. After fleeing to a military base, Charles de Gaulle announced new elections, and when they took place on June 23, 1968, his party gained even more seats. Not only did May 1968 fail to survive the summer of its birth, but France is now led by a man born nine years after the shock and awe of 1968 came to an end. If you utter “insurrection” in Paris today, you will likely conjure up images of the right-wing nationalist Marine Le Pen.

In the 50 years since 1968, many prominent radical figures of the time have turned to the right. David Horowitz, the Trump-supporting right-wing propagandist, had been the American New Left’s major theorist in the 1960s. His conversion pales in comparison to that of Benny Lévy, Jean-Paul Sartre’s last personal secretary and a self-professed Maoist, who became a passionate Zionist and died an Orthodox Jew in Jerusalem. Others did not turn right wing per se but did become supporters of a more militaristic turn in foreign policy in the name of humanitarian interventionism, none better known than Bernard Kouchner, the co-founder of Doctors Without Borders.

1968 may have ushered in a new world, but it is a far cry from the one the activists of those years imagined then. Donald Trump is the American president, neo-Nazis are gaining in Germany, Britain is turning its back on Europe, and recently liberated Communist countries compete over how far to the right they can turn. It can be no surprise that the half-century anniversary of 1968 is producing so many books aiming to make sense of it. What was it all about, this sudden outburst of activity? What were its consequences, and could it happen again? Or did it, in the end, signify very little? Both the academic I am now and the radical I was then want to know.

Revolutions, like suicides, are contagious. George Katsiaficas, the author of The Global Imagination of 1968, is, to modify a term from the German poet and essayist Hans Magnus Enzensberger, a tourist of many revolutions; his book comes endorsed by a parade of sometime-notorious activists including former Black Panther Bobby Seale; Ward Churchill, who once called the victims of September 11 “little Eichmanns”; and Shaka Zulu of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party and Jersey State Prison. Katsiaficas is worth reading partly for nostalgic reasons: If you have forgotten the existence of Lotta Continua in Italy or of the Brown Berets in California, he will remind you of their actions.

Taking a global perspective on the events of 1968, Katsiaficas has made a somewhat obsessive accounting of all the student demonstrations between April and June of 1968: West Germany saw 63; Japan, 9; France, 1,205. This data, culled from Le Monde, is fascinating; every region of the world witnessed youth revolts of assorted varieties. Richard Vinen, a historian at King’s College London, in 1968: Radical Protest and Its Enemies, cites a diplomat who suggests that Western Australia was the only place unaffected by the times. There are occasions when tourists of the revolution can play a healthy role, and this is one of them: As in 1848, when unrest in Sicily quickly spread to every part of Europe, there really did seem to be a spirit of 1968 that included not just Western Europe and North America but Eastern Europe and the Third World.

In retrospect, the most important of 1968 rebellions was not the Parisian one but the Prague one. Before Václav Havel became a household name, at least in intellectual households, Alexander Dubček and his conception of “socialism with a human face” became one of the most powerful sources of resistance to the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Proceeding very carefully, ever aware of the Soviet tanks facing in his direction, Dubček introduced reforms designed to encourage greater freedom of expression and a more flexible approach to industrial production. Although the Czech reformers bent over backward to accommodate Russian anxieties, the Soviets invaded in August 1968, bringing the dream of a more humanistic form of socialism to an end. The rebellion and its repression made clear that 1968 was not only a protest against capitalism and its appetites but against Soviet-style communism as well.

The very term “New Left” was designed to drive home that young radicals wanted little to do with the days of fellow traveling and united fronts. That might not have been as important in the United States, where Communists have had so little influence, as it was in France, where the French Communist Party (PCF) was not only large and powerful but took upon itself the role of judging whether a movement was properly revolutionary, concluding that all of them outside its own control were not. In Abidor’s oral histories, the filmmaker Michel Andrieu recalls an event on May 13 when he and his friends were confronted by henchmen from the Communist-dominated union the Confédération Générale du Travail, who threw them out of the demonstrations and tried to take their cameras. Another filmmaker, Pascal Aubier, was lectured by Georges Marchais, soon to be the leader of the French Communists, about how his movement was going to end badly.

The epicenter of early phases of the student revolt, the Paris suburb of Nanterre, was in fact governed at the time by the PCF, making a clash between the old and the new left inevitable. The PCF now launched at leftist students the kind of invective they once might have directed against capitalists. “These pseudo-revolutionaries who claim to give the working class movement lessons ... must be unmasked vigorously,” Marchais pronounced, “because, objectively, they serve the interests of the Gaullist power and the big capitalist monopolies.... The theses and activities of these revolutionaries might make one laugh.” In Eastern Europe, the students attacked the Communists. In Western Europe, the Communists attacked the students.

Marchais, nonetheless, was onto something when he said that the student rebels were serving the interests of Gaullism. Unlike the United States, France, as the sociologist Michel Crozier once pointed out, was a “blocked society.” Because French institutions were overly bureaucratic and resistant to change, the young and ambitious had little choice but to attack the whole system if they hoped to rise within any part of it. For this reason, May 1968 attracted not only protesters but potential power brokers who, once the 1968 struggles were over, would find successful leaders such as de Gaulle attractive. Régis Debray was in Latin America in May 1968, but despite his support for the Cuban Revolution, he later expressed admiration for de Gaulle, as did soixante-huitards Serge July and Alain Geismar. This all makes a certain amount of sense to Vinen, who notes that like the student radicals, de Gaulle “regarded the consumer society with disdain”:

He had opposed Israel during the 1967 war. He had opened diplomatic relations with China in 1964. He had withdrawn France from NATO’s joint command structures in 1966, and, most importantly, he had opposed American intervention in Vietnam.

When activists and would-be revolutionaries have more in common with the conservative establishment than with Communists, we know we are in strange territory.

In style, 68ers tended to be charismatic. One of the activists most responsible for the demonstrations in Nanterre was Daniel Cohn-Bendit. Central casting could not have provided a better version of a student radical: half German and half French, Jewish, and with red hair, “Danny the Red,” who later became a Green Party politician in Germany and a key member of the European Parliament, was especially hated by Marchais and the Communists (and he returned the favor). Another of the activists who talked to Abidor, Jean-Pierre Fournier, found Cohn-Bendit refreshing, contrasting him with the more “usual” activists such as Geismar and Jacques Sauvageot, who at the time was a leader of the Union of French Students. “He avoids coded, hidebound language,” Fournier recalled. “He spoke just like us.” He distinctly remembered Cohn-Bendit confronting Louis Aragon, the Communist poet, and calling him a “Stalinist lowlife.”

The tone of radical politics in West Germany was far more sober than in France. The recent memory of Nazism, defeated there little more than 20 years previously, provided an opportunity for conservatives to denounce the radical left as little different from Hitler and his henchmen: Even the liberal and humane philosopher Jürgen Habermas worried about the direction 1968 would take. The man who came to symbolize the German events of that year, Rudi Dutschke, as if to bury the shadow of Nazism once and for all, stood in sharp contrast to the flamboyance of Cohn-Bendit. Dutschke had little appreciation for the surreal and the absurd sides of leftist politics, and his influence stemmed from his modesty and inclusiveness. He was also shaped by the devout Lutheranism of his parents, was married to an American, and was scholarly in his interests and demeanor.

Shot during the 1968 events, Dutschke never fully recovered and died in Aarhus, Denmark in 1979. Ultimately, Dutschke’s major contribution was a phrase, “the long march through the institutions,” which provided a sense of meaning to 1968 activists in the quiet years that followed. The German Dutschke understood better than the French radicals Crozier’s idea of a blocked society, and he hoped to instill in the student left a sense of the seriousness of its actions. Instead of aiming to transform all of society, it was now the goal to transform work, the church, the university, and the family. These were no doubt huge ambitions in themselves, but they were nonetheless tethered to the real world.

In this, the 68ers did achieve a certain success: All major institutions have opened themselves up to change and become more meritocratic compared with how they operated before 1968. Whether this was a result of the student movement, or the demise of inherited privilege, the rise of affirmative action, or the reaction against affirmative action, or the spread of the internet, is still unanswered. But the more responsible of the 1968 protesters made it clear that they were in it for the long term. That may help explain the interest in those events half a century later. You never know when and where a former 68er might just pop up.

Some were less patient. West Germany, like the United States, soon became the home of left-wing terrorists: Here, they were called the Weathermen; there, the Baader-Meinhof gang. (There had been some direct connections between New Leftists in the two countries: Vinen tells the story of Michael Vester, a young German who played an important role in drafting the Port Huron Statement in America.) In sharp contrast to the 68ers like Fischer who became active in the Green Party, Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin were charged with setting fire to a department store in Frankfurt and tried in October 1968. Their legacy, the Red Army Faction, as their gang came to be called, was, in Vinen’s accounting, responsible for roughly 34 deaths.

Germany competed with Italy for the most deaths produced by 1968, whether measured in police violence against the protesters or by the actions of left-wing terrorists themselves. Italy won hands down: By Vinen’s accounting, 419 people died there between 1969 and 1987 as a result of left-wing terrorism. In either case, violence could not perpetuate itself indefinitely: The Red Army Faction committed its last violent act in 1993. Germany, a society responsible for so much violence in its recent past, was the last place to tolerate still more violence.

Protest and violence marked 1968 in America, too. That year, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, permanently changing the direction in which the country was headed. It was also the year of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam; the publication of the Kerner Commission report on urban violence; the sentencing of four of the Boston Five, including Dr. Benjamin Spock, for aiding draft resistance; major protests at Columbia University; the My Lai massacre; the Catonsville Nine burning of draft records; the premieres of the films Wild in the Streets and Night of the Living Dead; feminist protests against the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City; the “shot heard round the world” photo of a Vietnamese prisoner’s execution; the Mexican Olympics and the protests of Tommie Smith and John Carlos; the shooting of Andy Warhol by Valerie Solanas; the release of the USS Pueblo crew by North Korea; and the arrest of Timothy Leary in California on drug charges.

The events of that year proved to be far too big for Lyndon Johnson. LBJ’s 1968 by Kyle Longley, a history professor at Arizona State University, focuses on a number of crucial decisions Johnson made in 1968—just about all of which were disastrous. His refusal to bend over Vietnam represented little more than the victory of hope over experience; he heard what he wanted to hear and ignored the reality of the war America was losing. Moreover, Johnson knew that the 1968 Republican candidate Richard Nixon was working with Henry Kissinger to undermine peace talks with the Vietnamese, thereby helping Nixon’s own campaign in an action bordering on treason. Afraid that he would be viewed as trying to help Hubert Humphrey, Johnson refused to make Nixon’s efforts public, even when the press got wind of what was going on. For a man so adept in the ways of power, LBJ experienced 1968 as a long year of impotence.

Prague offers one more example of Johnson’s fecklessness. Determined not to undermine plans for a summit with Soviet leaders, Johnson chose not to contest the claims made by Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to the United States, that the Russians, in invading Prague, were simply trying to protect the Czechs from their own folly. This was, as LBJ’s adviser Clark Clifford put it, “a shattering moment, not only for Lyndon Johnson and his dreams, but for the nation and the world. History was taking a turn in the wrong direction that day, and there was nothing that anyone could do about it.” As brilliant as his political instincts were in the domestic realm, Johnson simply did not have the judgment to deal effectively with the global challenges that 1968 posed to America. Johnson not only botched both the war and the peace; he helped squash Hubert Humphrey’s attempt to replace him.

Compared to Hanoi and Prague, the Miss America contest that took place in Atlantic City in September 1968 may seem like small potatoes. In retrospect, it was an event of major significance. Reading all of these books on 1968, it is astonishing to recall that all the major decision-makers in the United States were men, with the noteworthy exception of Anna Chennault of the “China Lobby,” who helped further Richard Nixon’s duplicity by pleading with South Vietnamese leader Nguyen Van Thieu to resist signing any peace deal. The most vivid example is provided by the 14 so-called “wise men” who in March 1968 urged LBJ to begin to disengage from Vietnam; they were all male, white, and with two exceptions (Abe Fortas, a Jew, and Robert Murphy, a Catholic), Protestant. It is little wonder that feminist activists chose to protest against what they called the “degrading, mindless-boob-girlie symbol” represented by the pageant.

As if trying to mimic the ruling class they were seeking to oust, the New Left movements of 1968 were also dominated by men, many of them with the most reactionary attitudes toward women one can imagine. In 1964, Stokely Carmichael, then a field organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, declared that “the only position for women in SNCC” was “prone.” In the early days of organizations like Students for a Democratic Society, too, women’s voices were rarely heard, and the issue of gender equality garnered little attention. Among young radical men, free sex and drugs fueled fatal posturings of machismo and an atmosphere in which women were expected to reward courageous draft resisters with their bodies. It would not be long before those women formed, partly from these experiences, a radical critique of power relations between the sexes.

As if the events of 1968 were taking place in a totally different world, that year saw in the United States the election of Richard Nixon. Lawrence O’Donnell published a history of the 1968 campaign last year, and this year has produced, so far, at least half a dozen more treatments. For the most part, they cover the same stories, relating how Allard Lowenstein, an activist and aspiring politician, searched for a protest candidate to challenge Johnson and eventually persuaded the otherwise ambivalent Eugene McCarthy to run, and how after McCarthy’s surprising performance in New Hampshire, Robert Kennedy jumped in. Johnson surprised everyone by withdrawing from the race (although he made clear that he would accept a draft); Hubert Humphrey experienced repeated humiliation from LBJ before, at the very last minute, finding his voice; Ronald Reagan made his first run for national office; George Wallace and his independent candidacy displayed a bit of Trumpism before Trump; and Nixon chose, of all potential leaders, Spiro Agnew to be his running mate.

Charles Kaiser’s 1968 in America—published 30 years ago and now reprinted for the 50th anniversary—magically conveys the spirit of the times, blending his treatment of the election that gave us Nixon with the culture that gave us Grace Slick, Jim Morrison, and Marvin Gaye. Kaiser’s chapter on rock and roll is, in fact, the best in the book. He identifies as the “one man” who “did more than anyone else to break down the barriers that had traditionally kept American musicians apart” in the years before 1968 John Henry Hammond Jr. Born to wealth—his mother was a Vanderbilt—Hammond possessed an astonishing ability to discover talent and, more importantly, to cross racial lines in bringing that talent together. Without him, Billie Holiday, Sonny Terry, and Aretha Franklin, among many others, might still be unknown to white audiences.

Kaiser downplays, wrongly I believe, just how much white musicians essentially stole from black artists. But he rightly understands how much the tumult of the times shook all previous alignments, including racial ones. “Through television,” Kaiser concludes, “the Vietnam generation participated in a terrible tide of death and destruction as the political center repeatedly failed to hold during the balance of the years. But in their worst moments, the children of the sixties took solace from the music that kept rolling out of the radio.”

So what shall we make of this year of discontent? Richard Vinen concludes his book, easily the very best of the newly published ones being considered here, with this observation: few 68ers became hippies on communes, terrorists, government ministers or multimillionaires but the majority had unspectacular careers that often involved a degree of self-sacrifice.” I think he gets the balance precisely correct: 1968 without question changed lives, but it is an open question how much it changed societies—and in what direction.

1968 certainly changed me. Graduating college in 1963, the closest I had come to politics was a brief fascination, common among young male idealists at the time, with the novels of Ayn Rand. Having outgrown her simplemindedness but unsure what to believe next, I traveled to Nashville, Tennessee, to enter graduate school at Vanderbilt, a sure way, I correctly believed, to escape the draft. What came next quickly became obvious. Overt, explicit, state-enforced racial segregation, which I encountered in Nashville’s streets in the year before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, was so blatantly unjust that not protesting against it became unthinkable.

Arrested, jailed, and tried (fortunately the case was eventually dismissed), I encountered among fellow protesters, many of them students at either Fisk or Tennessee A. & I. (now Tennessee State), a sense of moral urgency, a compelling love of gospel music, and a commitment to lives of purpose that put me and my white, middle-class typicality to shame. When my arrest made the hometown newspapers in my native Philadelphia, my mother flew down to Nashville to make sure I was OK. I took her to hear Martin Luther King Jr. preach in a black church, and she never stopped talking about it afterward.

It was said at the time that the personal was political, but for me that phrase took on special meaning. I left Vanderbilt before one year was up when my wife, Brenda, who had had a persistent cough that turned out to be a deadly form of cancer, died soon after our marriage. Just over three years later, my sister Bonnie was taken ill, and she too passed away, this time from an inflamed colon. A few weeks after that, Martin Luther King was shot, then, in just two months more, so was Robert Kennedy. I had already been involved in left-wing politics, but the deaths that took place that year transformed my indignation over racial discrimination in the South and cruelty in Vietnam into powerful and frequently destructive anger: There I was in the streets, cheering slogans, risking arrest, inhaling tear gas, occupying buildings, flirting with Marxist theories, giving advice to students, rejecting King’s nonviolence, and experimenting with sex and drugs. For me, 1968 was a time of both liberation and despair. I literally did not know which end was up.

I was all of 26 years old in 1968. I had never been outside the United States, never lived in anything but a middle-class environment, and, save for one week, never worked in a nine-to-five job. But here I was telling people how to make the world a better place. I shudder now, 50 years on, to recall the know-it-all I was then. But 1968 was capable of doing that sort of thing. Thirty, Jerry Rubin had announced, was the cut-off point, and I still had four years to go. Because the whole world was going up in flames, we knew we must have been doing something right.

In subsequent years, 1968 brought about more than its share of recriminations. A number of writers and intellectuals, some of whom were my building-occupying comrades, expressed “second thoughts” about the radicalism of their youth. My mind does not work that way. To be sure, when I think back to 1968, I shudder at my immaturity, selfishness, and lack of responsibility: The events of that year were changing people, and I was in desperate need of change. Yet all the mistakes I made back then leave me with little or no sense of shame: Dostoyevskian reflections are not my cup of tea. Not even the horror of the Trump years can make me forget all the lies told by Lyndon Baines Johnson to justify the deaths his political cowardice caused in Vietnam.

Once you had seen someone like Spiro Agnew elevated to the vice presidency there seemed no bottom to how low American politics could sink. To be sure, Sarah Palin came close, but she never actually held national office. In 1968, the politics of race had not yet turned in a nationalistic direction, and identity politics was just in the process of formation. Was I wrong to have been swept up in the more exotic manifestations of that year? Knowing how young I was then and how much tragedy I had experienced, I do not think so. I was an idealist at an idealistic moment. That is not a bad place to begin the process of maturing.

Since 1968, America has gone off in a different direction than I had hoped: Reagan, Nixon, and Trump are not the kind of leaders we had in mind back then. In 1968, I would have settled for nothing less than socialism. Twenty-five years after that, something like a European welfare state would have made me happy. Today, just having a reliable subway system appears utopian. The French Revolution, however violent, uprooted the monarchy. The Russian Revolution, however perverse, produced an experiment, albeit a failed one, in economic planning. 1968 not only failed to achieve most of its goals, it set politics off in the wrong direction.

Yet the story does not end there. It pleases me beyond measure that young people today are leading so much of the opposition to Trump, the reactionary right, and the NRA. Let them have much of what I had in those glorious but also frightening years: burning conviction, solidarity, euphoria. Only this time, let them win.