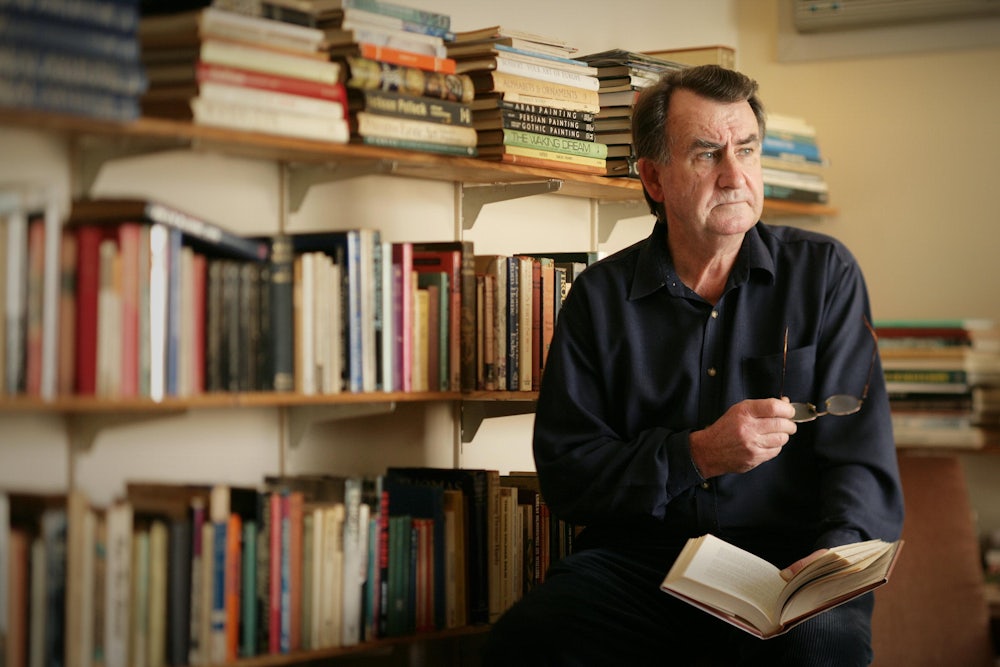

At the very moment of his breakthrough, Gerald Murnane is threatening to disappear. The 79-year-old Australian writer—long considered a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, an association that speaks both to his genius and obscurity—is enjoying a rare moment in the sun. As he told The New York Times Magazine in a recent profile, “My publishing history’s just so checkered with sudden reversals, ups and downs, confusions, wrong turnings, and at the end of my life, virtually, it seems like things are starting to work out.” He has a new home with a major U.S. publisher (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, after many years with various independent houses), which has released two volumes of work previously unavailable to a general American readership: Stream System, his collected short fiction, and Border Districts, a novel. Yet these books have the feeling of a farewell: The first is a career-spanning overview, while Murnane has said that the latter is his final work of fiction.

Murnane has abandoned writing before, in the 1990s, when he despaired at the world’s indifference to the private obsessions that form the backbone of his books. His stories are not plotted in the traditional sense. His characters are not “rounded” in E.M. Forster’s terminology. In most stories there is, in fact, only one lifelike character, sometimes referred to as a “personage” or “implied author,” who dwells on various images—the face of a woman, a horse jockey’s racing silks—that swim up from the depths of memory or imagination or some numinous combination of the two. His books are only tenuously connected to what his narrators disparagingly call the supposed real world. As Murnane told the online magazine 3:AM: “I have no time for those writers of fiction who find their subject matter in the news headlines; who turn the so-called issues of the day into fiction.”

It may be that literary trends have finally caught up with Murnane. If he was lost two decades ago, playing all alone in the perpetual twilight of fiction’s borderlands, his work can now comfortably be described as belonging to the genre of autofiction, popularized in recent years by writers like Karl Ove Knausgaard, Ben Lerner, and Rachel Cusk. His blending of memoir with fiction, essay with short story, has become chic, a word that no one would apply to Gerald Murnane in any other context. He remains an extreme case, so inward as to be a bit alien, ensconced in his eccentricity like Don Quixote in his armor. Indeed, that Murnane is a bona fide oddball is a central theme of the lore that surrounds him: He has never traveled outside Australia, according to reports, and only occasionally outside his home state of Victoria, in the southeast of the country. He has never flown in an airplane or gone swimming or worn sunglasses.

In a sense, Murnane has always been on the cusp of disappearing. He has a toehold in this world, while the rest of him shades into another. In a networked age that has simultaneously left people more atomized than ever, it is hard to tell if he is an anomaly of modern life or its apotheosis. What is clear from these two new books, however, is that there is something about his disappearing act that transcends mere isolation or self-absorption, that has special resonance in the country where he was raised and where much of his fiction is nominally set—a country that has never fully come to terms with its dark origins. Murnane may be an island, but that island is, in more ways than one, a continent.

Few critics have paid much attention to the relation between Murnane’s work and his country. Australia is the almost arbitrary place where this savant of letters was born. As J.M. Coetzee has written, “Murnane is conspicuously absent from the list of Australian writers who have answered the call to celebrate or interrogate Australianness.” Murnane is often compared to Borges and Calvino, which arises, I think, from the perception that these novelists are akin to mathematicians, operating in the naked realm of the mind, crafting a fiction as pure as a theorem. The sense that Murnane’s work resides in some abstract plane is heightened by his chief subject matter, which he calls the invisible world.

“There is another world but it is in this one.” This sentence, attributed to the French poet Paul Éluard in Murnane’s 1988 novel Inland, is a keystone for Murnane’s life and fiction. It is what connects Murnane’s flinty Catholic upbringing—which culminated in a brief flirtation with the priesthood as a young man—with the monkish, otherworldly concerns of his books. His loss of faith apparently did not diminish his intuition that there was a universe beyond the terrestrial. The narrator of Border Districts, a quasi-Murnanian figure who has moved to a remote town to contemplate the memory-images of his life, says of Christian icons whose religious significance has been purged: “Those that had always appeared to me as depictions in stained glass were still lit by the same glow from their further sides.”

The source of that light, lying on the other side of the visible world, is what preoccupies Murnane. When his characters look out windows onto level fields stretching to the horizon, as they invariably do, they are simultaneously peering inward. When they unfurl maps and pore over atlases, another habit of Murnanian characters, they are also surveying the topography of the deep interior. The invisible world is composed, quite simply, of images and the feelings associated with those images. They are not less real than anything in the visible world—to the contrary, they are more real, since the visible world is fleeting, mortal, meaningless, except for what crosses the threshold into the invisible world and is captured there like a snapshot. The writer’s purpose is to decode the significance of these images, to ascertain why they make him feel the way they do, and to render them visible.

Hence Murnane’s disdain for so-called real world. Hence his insistence that his “characters” (which implies an ersatz quality) are “personages” (which suggests they are not much different from persons). Hence his reluctance to distinguish between thinking and remembering and imagining; between women in books and living-and-breathing women and women long dead; between his mind and the universe. Hence his obsession with fiction, where, as he writes in the story “Stone Quarry,” “the invisible was on the point of becoming visible.”

Murnane takes the themes of Proust, the patron saint of autofiction, to the bleeding edge of mysticism. For Proust, what is “real” is defined by involuntary memory—the sudden resurrection of life in all its multifaceted glory—whereas mere experience, dimmed by habit and ultimately destroyed by time’s lava flow, is but a “mock reality,” as Beckett described it in his monograph on Proust. The writer’s calling is to set that memory in the amber of his prose; in Proust’s pitiless formulation, art is all, life is nothing. For Murnane, the same principle holds, but with the difference that he stretches art’s link with life to the breaking point. His world can feel like a shadow world—with its own physics, its own inscrutable symbols, its own ghostly population of paper people—eclipsing the real one.

The above is merely a rough sketch of Murnane’s all-encompassing schema. To read Murnane at great length—to read, say, nearly 550 pages of his collected short fiction—is to feel as though you are reading some variation of the same story over and over again. Personages mull the ideal combination of colors for horse-racing silks. They stare at books on the shelves and try to recall the sentences within them. They dream of the prairies of America and Hungary, which look like the grasslands of Australia. They fall in love with women—“image-women,” to be accurate—who may all stem from an ur-woman inspired by the characters Tess Durbeyfield and Catherine Earnshaw. It goes without saying that they read a lot of Proust and Emily Brontë and Thomas Hardy.

The repetition is deliberate. As Murnane’s implied author writes in his 2009 novel Barley Patch, “I may have written during the past thirty years and more not one after another separate book but one after another chapter of the one book, the final chapter of which I am trying to write at present.” Murnane’s work has been described as “fractal,” its basic pattern recurring at every level, from sentence to paragraph to story to novel to oeuvre. As the narrator says in the story “In Far Fields”: “My last book would be a book of books: a distillation of precious imagery.” This is, essentially, a description of Border Districts, which, at roughly 130 pages, is not much longer than the longest story in Stream System.

Repetition is also a feature of Murnane’s prose style. His implied author has a naïve affect, as if describing the world for the first time at an anthropologist’s clinical remove. (“Stream System” is an almost zoological way to denote a human being, composed of streaming blood vessels.) The sentences are laid on like varnish, coat after coat, until the text gleams with a high shine. Immaculate in its unadorned plainness, at certain moments his prose achieves a crystalline beauty. To take one example from Barley Patch:

He had often placed one after another translucent marble so that the sunlight would cause a patch of faint colour to appear in the shade of the marble. After he had learned from his reading the word essence, he thought of the patch of colour as revealing the essence of the marble.

Or to use a more melancholic line from the brilliant story “Emerald Blue”:

Even to his wife and children he had sometimes said that Sunday afternoon was the saddest time of the week: the time when you had to admit that you were no more than the person you were.

The paragraph concludes with a typical metaphysical twist, with the narrator stating that, in addition to being a father and husband, he is a “much published and much renowned poet” in a fantasyland called Helvetia.

Herein lies the appeal, for certain readers anyway, of Murnane’s writing: the cosmology that issues forth, like a blooming cloud, from the memory of everyday events—handling a marble, following the elliptical course of a racetrack, holding a girl’s hand. “[L]etting his hand find her hand and her letting her hand lie in his hand until they reached her front gate were, at the very least, equal in meaning to any other events that occurred in the lives of any other person in the world during his and her lifetime,” says the narrator of “Emerald Blue.” Each story works toward a pattern involving the memory-images in question, just as the pattern of a single life comes into greater focus as it approaches its end.

The pattern of Murnane’s body of work has also become more apparent, particularly with the publication of Stream System. He may like to present himself as a fantasist of the mundane, hunched over his trinkets like a jeweler examining diamonds, but these stories are strewn with enough references to history to suggest that he is fully aware of the context from which his writing springs. If Murnane strives to disappear—into himself, into the invisible world—he has indicated that this drive lies at the heart of the Australian experience.

Australia’s vastness and remoteness are recurring motifs in Stream System. His characters share the persistent sense, common among non-Westerners, of being cruelly detached from the center of the world, where the films are made and the books are written and the wheels of life are turning. But the antipodes offer singular rewards in recompense. In “The Only Adam,” Murnane interrupts a story of an adolescent crush with a quote from Thomas Livingstone Mitchell, one of Victoria’s earliest European explorers, who in the 1830s reveled in the glorious land that lay before him, “with all its features new and untouched as they fell from the hands of the Creator. Of this Eden it seemed that I was the only Adam; and indeed, it was a sort of paradise to me.”

This could be a description of Murnane’s project: the invisible world suddenly made visible, presided over by a single, totally autonomous being. The writer’s most “precious resource,” Murnane writes in “Stone Quarry,” is the “belief that he or she is the solitary witness to an inexhaustible profusion of images from which might be read all of the wisdom of the world.” In “Cotters Come No More,” a young writer makes the connection to Australia explicit in a Joycean soliloquy:

We were at the very southern edge of an enormous land whose fund of poetic inspiration had barely been tapped. … It was our responsibility to preserve in poetry what no one else had written about. And it was our right to be free to search for the most apt words unhindered by history or tradition.

The last sentence self-consciously prompts the questions: Whose right? And whose history? Included in Stream System is perhaps Murnane’s best-known story, “Land Deal,” a five-page fable centered on the explorer John Batman’s 1835 barter to secure a parcel of land from Aboriginal Australians in what is now Victoria. Besides a few oblique references to Indigenous people in Stream System, “Land Deal” is the only story that addresses their plight directly. And yet it is another keystone to Murnane’s work, offering an implicit criticism of what we now call autofiction and of what could be described as Murnane’s Australianness. Told from the Aboriginal Australians’ perspective (a departure for Murnane) and in the first-person plural (ditto), “Land Deal” is a surreal meditation on this fateful encounter, as the narrators slowly realize that the settlers have a strange vision for the land, “the founding of an unheard-of city where they stood.” It dawns on them that they are trapped in the vision, “no more than characters in the vast dream that had settled over us.”

At one point in Coetzee’s novel Elizabeth Costello the titular protagonist describes her writing this way: “Making up someone other than yourself. Making up a world for him to move in. Making up an Australia.” Gerald Murnane’s myriad personages move in such a world, even if he would assert that it is no more made-up than the Australia that exists today. But there are no private worlds, not really, when one man’s heaven is so palpably another’s hell.