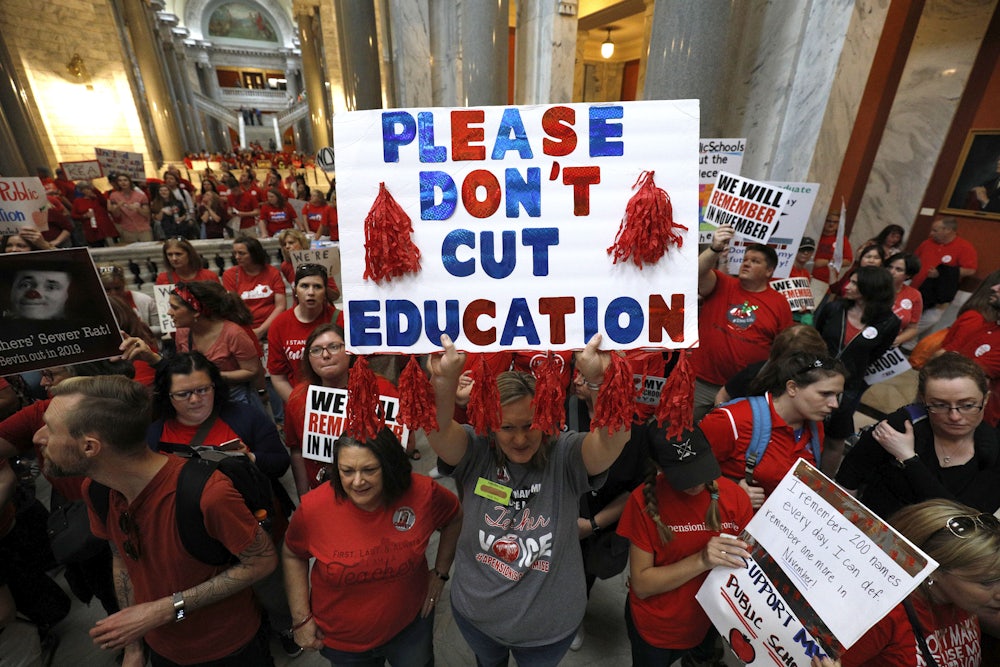

Weeks after public school teachers across the state walked out of class, the Kentucky Department of Education has recommended that the state assume control of Kentucky’s largest school system. Commissioners appointed by the state’s Republican governor, Matt Bevin, would have final say over the affairs of the Jefferson County public school system, which serves the city of Louisville and surrounding areas. Opponents of a takeover say state control may not necessarily be the answer to the county’s problems. They’re concerned that this may be the prelude to greater privatization of the system, which itself could be part of a retaliatory campaign against the teachers and their supporters.

Jefferson County is largely Democratic, and it mostly supported April’s walkout; in fact, the district was home to some of the state’s earliest teacher sickouts ahead of the large-scale walkouts that captured national attention. Jefferson County, therefore, challenges the authority of a governor who does not appreciate such challenges.

It’s important to establish that the school system does have real problems. An audit, launched by the state’s previous education commissioner and released by its current one, accuses the district of improperly managing funds, inconsistently implementing curriculum, and failing to appropriately address cases of student abuse. In January 2017, a kindergarten student with special needs broke his thigh bone at a Jefferson County elementary school; in 2014, administrators at another school in the county broke a teenage boy’s femurs when they restrained him. The question is not if Jefferson County Schools need improvement. Rather, it is a question of whether state control is the answer, particularly when the state could use such audits as a Trojan horse to introduce privatization measures.

It isn’t clear if Jefferson County schools are disproportionately worse than schools in any other Kentucky county. It’s even less clear that the administration of Bevin, who adamantly supports charter schools and school vouchers, has any real interest in investing the funds necessary to improve such a large and complicated public school system. Furthermore, the district may not have much leeway to object if the state does take it over. Although education commissioner Wayne Lewis and Bevin have both said they support Marty Pollio, the district’s current superintendent, Lewis will be able to make significant decisions over Pollio’s head.

The takeover proposal also follows recent upheaval in the state board of education: In early April, Bevin packed the board with his own appointees, forcing the sitting commissioner, Steve Pruitt, to resign. The board subsequently appointed Lewis, a charter school advocate, as interim commissioner. Pruitt initially commissioned the audit into Jefferson County’s operations, but Lewis released that audit after barely serving two weeks in the job.

Lewis hasn’t yet proposed charters as a solution to Jefferson County’s problems. But he’s promoted them in the past, and served as chair of the Kentucky Charter Schools Association. The Louisville Courier-Journal reported in April that Lewis has said charter schools are a “powerful new tool to help increase achievement, reduce achievement gaps, and prepare students for success.”

Local parents and educators are further disturbed by some of the audit’s findings. Among them: that the county’s student assignment plan places an undue burden on district transportation staff. The student assignment plan, however, is the result of a busing order intended to enforce the desegregation of Jefferson County schools. And although the audit itself didn’t examine teachers’ unions, Lewis nevertheless announced the day of the audit’s release that the next contract for the district’s bargaining unit must “reflect systemic changes that have begun or that will take place as a result of state management.”

“Any bargained contract must enhance, not inhibit, the ability of the district to deliver quality educational services to all students; provide needed professional development to district staff; hold district staff accountable for illegal, unethical, or unprofessional behavior; and attract and retain high quality staff in struggling schools,” he wrote, as initially reported by WDRB News. The takeover proposal isn’t a direct reaction to April’s walkout, but it is on the state’s mind.

Attica Scott, a Democratic state representative who represents Jefferson County, told me that she isn’t surprised by the takeover proposal. “In passing charter school legislation in 2017, the governor showed he was determined to move toward privatizing education in Jefferson County specifically,” she said. “There was also an attempt by the Republican majority to end the busing system as we know it in Jefferson County, though that fortunately did not pass. So this is part of the governor’s agenda, which he is literally forcing on us by the underhanded tactics he used to get this commissioner.”

Scott doesn’t see the takeover as a retaliation for the walkout, but instead believes it’s part of a longer-running grievance campaign by Bevin, targeting one of the state’s few reliably Democratic districts. “He has been out for Louisville since he was elected,” she told me. Bevin’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Rob Mattheu, the parent of a child in the Jefferson County school system, told me that he hopes the district fights the takeover. “This is the first time that I feel like we have really good leadership, a really good school board,” he said. Mattheu supports the continued leadership of Pollio, who became the district’s acting superintendent in July 2017 and officially assumed office in February of this year. Whatever problems the district has, he claimed, can be placed at the feet of Pollio’s predecessor, Donna Hargens. Hargens agreed to leave her post in 2017, after pressure from the district school board.

“I think it’s perfectly reasonable to say that Jefferson County Public Schools have issues,” he added, “but it bothers me that they don’t point at the person under whose leadership it failed, and they just say it’s time to take it over. I think they’re looking for a strategy to do just that.”

Wood and Mattheu are right to worry. Jefferson County wouldn’t be the first county taken over by the state. The state also took over Floyd and Breathitt counties, both located in the eastern coalfields. For Breathitt, the consequences of the takeover proved dire. The state’s appointed superintendent cut 60 jobs, closed an elementary school and day care, and raised property taxes by 4 percent—all major blows to Breathitt, where one-third of the population lives below the poverty line. Breathitt, like Jefferson County, did have significant problems ranging from corruption to managing drop-out rates. But it’s possible to attribute other issues, like inadequate facilities, to local poverty. It’s difficult to believe that the loss of 60 jobs and a commensurate raise in property tax did much to alleviate that particular problem.

In the case of Jefferson County, an urban district with complex needs, a state takeover could actually erode the progress schools have already made. “It’s important for people to understand that Jefferson County Public Schools is a district that is rich in diversity of all kinds,” Scott said. “I’m talking economic diversity, geographic diversity, diversity in terms of students from different religions and ethnicities and races and students who are queer and gender nonconforming.”

Mattheu, whose daughter is enrolled in a magnet arts program, also worries that his existing level of school choice will disappear. “What if they come in, in her final year, saying guess what, her high school is now no longer teaching art?” he asked. “Or there’s a kid who’s now in seventh grade that finds out that his program no longer exists? Those decisions will be made at a state level. That’s not fair and it’s not democratic.”