In a tweet on Friday, President Donald Trump laid out the likely Republican messaging strategy to hold on to Congress in this fall’s midterm elections: warn voters that Nancy Pelosi, the leading Democrat in the House, is going to raise their taxes if her party takes control of the chamber. Or in Trump’s words:

Nancy Pelosi is going absolutely crazy about the big Tax Cuts given to the American People by the Republicans...got not one Democrat Vote! Here’s a choice. They want to end them and raise your taxes substantially. Republicans are working on making them permanent and more cuts!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 20, 2018

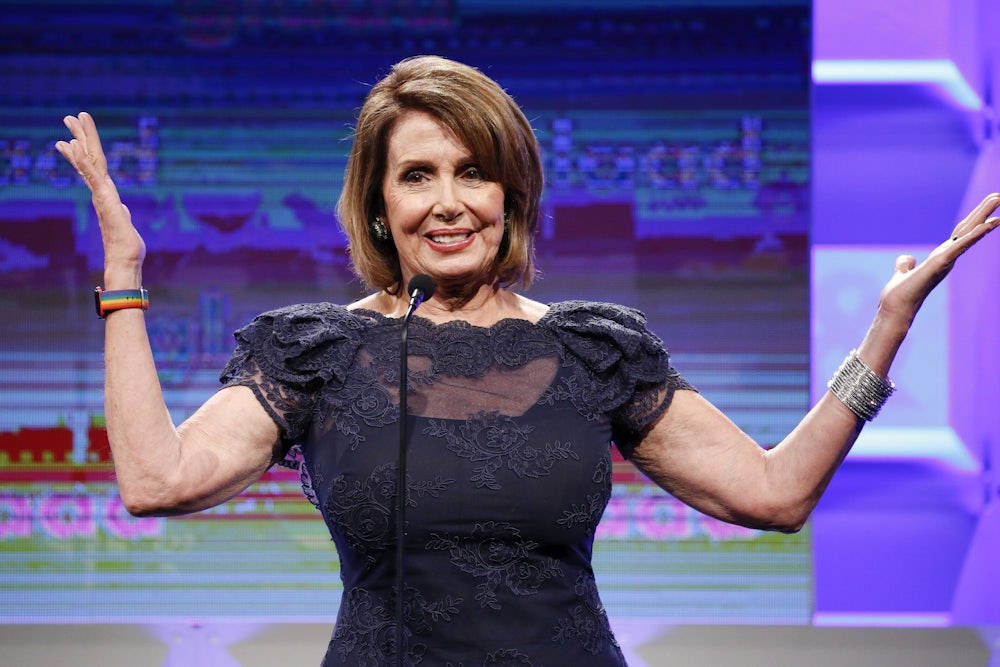

While Trump is often accused of interjecting a new level of acrimony in American politics, his attack on Pelosi is perfectly in keeping with the Republican mainstream. Pelosi has been a major GOP target ever since she became House Minority Leader in 2003, and the onslaught is only increasing in intensity. And with both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton retired from public life, Pelosi has become Republicans’ scapegoat of choice, the Democratic politician most likely to be used in attack ads designed to rile up the conservative faithful.

“Nancy Pelosi has long been a favorite target of GOP attack ads,” USA Today reported recently. “But Republicans seem to be taking it to another level in this election cycle.” 34 percent of Republican ads in House races this year mentioned Pelosi, up from 13 percent from the 2014 midterm cycle. In some races, this is the dominant message: In the special election in Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District last month, 58 percent of Republican ads were anti-Pelosi.

Republicans became obsessed with Pelosi the moment she ascended as a national figure. In 2003, Los Angeles Times observed that Republicans were “eager to attack Pelosi as a loopy San Francisco liberal and exploit her city’s reputation as the odd-sock drawer of America. Within days, her face—garish and twisted—showed up in an attack ad slamming the Democrat in a Louisiana House race. (He won anyway.) She surfaced as Miss America, complete with tiara, in a spoof on Rush Limbaugh’s Web site.”

The relentless demonization of Pelosi, who has reached the highest office of any female politician in American history, is partly fueled by—and an appeal to—sexism. “I think they need to get a new game book,” Representative Joseph Crowley, chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, said last month of Republicans. “The attempts to use Nancy Pelosi, it’s failing them at this point. And I think, quite frankly, it’s sexist.”

But Republicans’ animosity toward Pelosi is also certainly driven by fear: As both the minority leader (from 2003-2007 and 2011-present) and House speaker (from 2007-2011), she has been an accomplished and indomitable captain of House Democrats.

Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution has hailed her as the “strongest and most effective speaker of modern times” because of her success in securing stimulus funding in 2009 and overseeing the passage of the Affordable Care Act the following year. As Peter Beinart pointed out in this month’s Atlantic, “even after being relegated to minority leader when Republicans took the House in 2010, she kept winning legislative fights. In the summer of 2015, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and the Republican Party launched a mammoth lobbying campaign to kill Obama’s nuclear agreement with Iran. Pelosi quickly secured the votes to prevent Republicans from overturning the agreement, thus checkmating the deal’s foes.”

Pelosi’s record of success is a marked contrast to her Republican counterparts’ during the same era, ranging from Dennis Hastert to Tom DeLay to John Boehner to Paul Ryan. They presided over a Republican Party that theoretically should have been more unified than the Democrats, since it is more ideologically homogenous, but is in fact riven by factional fighting. Ryan’s feeble leadership today, marked by only one major achievement (the 2017 tax cuts) and an increasingly hollow ideological agenda, is representative of the larger GOP failures of this era.

Pelosi is a Democratic powerhouse in an era where the two parties are dividing along gender lines. This is not just a matter of the gender gap among voters or Donald Trump’s long history of sexism. Democrats are much more likely to have female lawmakers than Republicans are. A third of all Democrats in Congress are female (78), whereas just 9 percent of Republicans are (26). “Democrats, even though they are outnumbered by Republicans, have three times more women in the two chambers,” Politifact noted.

Republicans are, of course, attacking Pelosi because they think it’s a winning strategy. Her liberal track record makes her especially unpopular in Republican-leaning districts, where Democrats are hoping to pick up seats by fielding more centrist candidates. But it’s not clear that these attacks work.

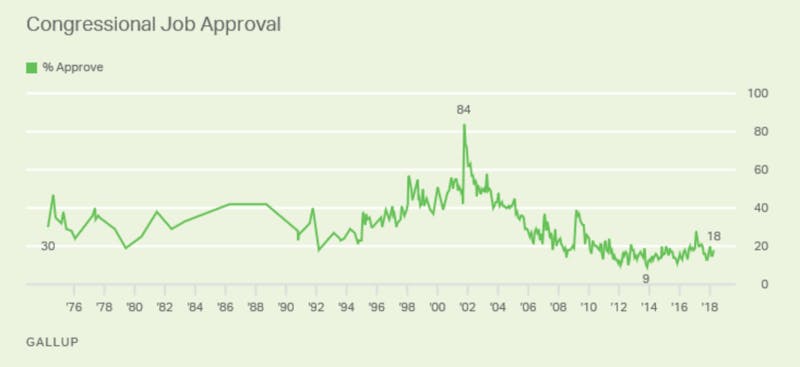

Congressional leaders have long been broadly unpopular because they’re among the most visible figures in Congress, which itself is broadly unpopular. This is especially true in the House, which is the more divisive of the two chambers because the small size of its representative districts—relative to statewide Senate seats—tends to produce more extreme candidates.

But as Harry Enten of CNN pointed out, the history of using congressional leaders as bogeymen has seldom yielded measurable success. “Democrats tried to run against Newt Gingrich in 1994 and 1998,” he wrote. “They did the same in 2010 and 2014 against John Boehner. Their record is at best mixed, as the president’s popularity has been the most important factor.” The latest evidence of the strategy’s limits: Democrat Conor Lamb won last month’s special election in Pennsylvania, despite the 59 percent of Republican ads trying to tie him to Pelosi.

Pelosi is a polarizing figure nationally, but she’s popular with Democrats. As Politico reported in June 2017, “Pelosi has a 2-to-1 favorable-to-unfavorable rating among Democrats, 49 percent to 25 percent. But her ratings among Republicans (21 percent to 63 percent) and independents (20 percent to 52 percent) are far worse.” When polling questions about Pelosi are linked to specific issues, Pelosi does even better. A CNBC poll showed that 49 percent of the public agreed with her that corporations got reaped a windfall from the GOP tax cuts while only giving workers “crumbs.”

If the Republicans continue to throw darts at Pelosi, it may be because they have no alternative. Except in the most pro-Trump districts, Republicans can’t run wholeheartedly in praise of a historically unpopular president. And Republicans are much more reliant on negative partisanship than their opponents, defining themselves in opposition to Democrats rather than for a positive agenda. That’s especially true after last year, when Republicans had unified control of the government but failed to repeal Obamacare and only managed one major legislative achievement. This year, Congress is widely expected to be even quieter.

As Pelosi sees it, the sad state of the GOP policy agenda forces them to smear her. “This is part of the bankruptcy of the Republican Party,” she said last month about her prominence in GOP attack ads. “They’re devoid of ideas about how they can meet the needs of the American people, so it’s an ad hominem.”