I’ve been worried about the trees. This week, The New York Times headlined a morning update “New York Today: Winter in Spring.” It’s just been cold for so long, a meteorologist told the paper. On the approach to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to visit its new show Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence on Thursday, I could see a magnolia tree in bloom at the edge of Central Park but no buds on its starker neighbors.

Inside the Met, however, things are green. If you march all the way to the back of the museum you will find a ring of galleries around a sort of piazza, where you can sit on benches amid ficus, strelitzia, howea forsteriana. The piazza isn’t quite a garden or a public park, but it is a quiet place to rest under light that streams in from high windows.

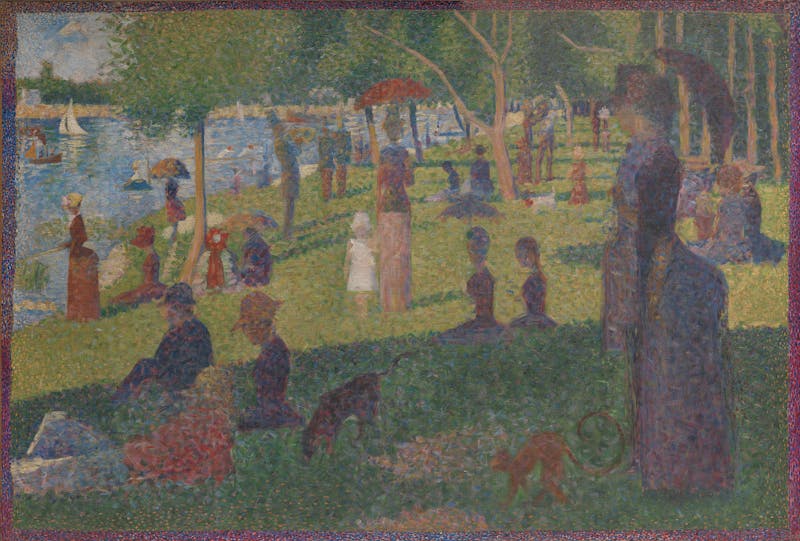

The show was supposed to be “timed for the advent of spring and summer,” since it is dedicated to art depicting the outdoor leisure spaces of France, from the Revolutionary years through the nineteenth century. But the gallery is warm, so you can imagine yourself in the balmy garden at Giverny, instead of 83rd Street. Here are many familiar paintings: a study for Seurat’s enormous A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, some Monet waterlilies, Van Gogh’s irises (though these last have been inexplicably shoved into a corner). There are also ceramics—since vases hold flowers—alongside horticultural engravings and objects from the garden like shears and watering cans.

The immediate effect as you walk in is of being inside a tea towel. That’s because we associate the floral and the Impressionist so strongly with decoration. There are many painters here—Van Gogh, Monet—who have become the backdrop to our lives.

But the exhibition’s political inflection saves it. The show is divided between the public and the private spheres. The design of outdoor space changed after the Revolution, as did art about that space. The André Le Nôtre gardens at Versailles are justly famous, as are the Tuileries: Their formal boulevards have the kind of symmetry that stills a worried heart. But the gallery “Revolution in the Garden” shows how the “naturalist” style of design took over the French garden after 1789. Flowers in particular became the great thing in the early nineteenth century, in part because of the influence of Napoleon’s wife Josephine Bonaparte.

In post-Revolutionary Paris, the plan of the city changed. What had been royal land became public parks, or capacious and leafy squares. In “Parks for the Public,” we see works by Corot, Enfantin, Monet, Cuvalier, and many artists of the Barbizon school depicting Fontainebleau, the forest near Paris. Politically, that forest represents the new accessibility of royal hunting lands to ordinary people. Painting can assert ownership over the subject. But Corot’s stirring account of a group of trees asserts instead a kinship—he the painter, and they the trees, are co-existing phenomena in a Republic.

The boom in floriculture inspired by Josephine Bonaparte drew wild strength from imported botanical specimens and the horticulturists who coaxed these new, augmented materials into a garden culture. In tandem, a rise in still life painting of flowers grew. This room, “The Revival of the Floral Still Life,” is the least appealing of the show. It features fine works by Courbet, Van Gogh, Manet, Delacroix, and Degas. But vases of flowers on tables have been cursed by their own prettiness. In our age of endless reproduction, Van Gogh’s sunflowers emit a strong smell of plastic fridge magnet. The exception is Matisse’s Pansies (ca. 1903). That painting makes you feel like you’re being pleasurably electrified.

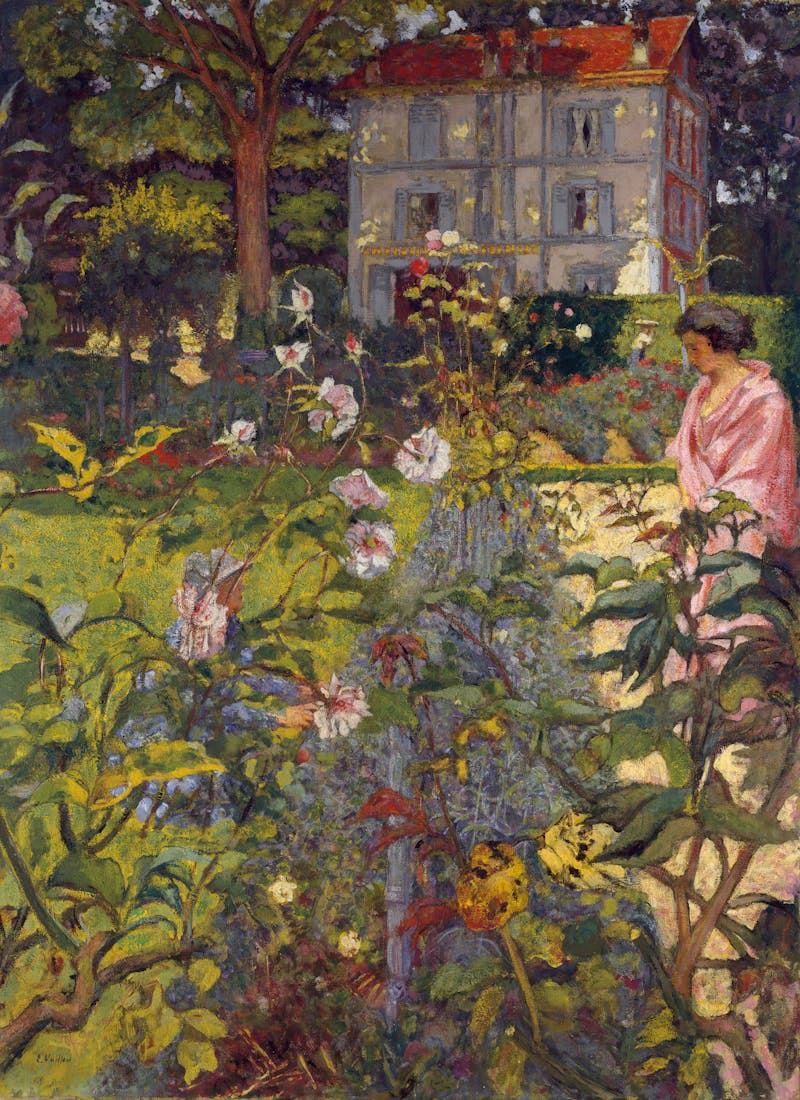

It is fortunate, therefore, that the two galleries dedicated to private gardens are so utterly beautiful. “Private Gardens” and “Portrait in the Garden” are home to works by Impressionists who cast their loving gaze over flowers, women, the private sanctum. Bonnard’s From the Balcony (1909) shows children tumbling below on the lawn, under waving trees. Standing in front of it, you can sense that special feeling of the threshold between house and garden, between standing on the lawn and standing on the balcony.

Space is emotional, and it is political. Caricatures in this exhibition show how silly people look when they go mad for cultivating their little patches of land. Drawings by Daumier and Flaubert depict well-to-do Parisians in absurd smocks, caught up in a middle-class craze. Having one’s own land is like being the king of one’s miniature country. Nothing about gardens is “natural” in the sense of the word as meaning untouched or wild. It’s an enclosure under the gardener’s total control.

Ridiculous or not, I would have worn that smock if it could have got me into Jas de Bouffan (Cezanne’s family estate). Cezanne’s painting of the pool in that garden is neck and neck with Corot’s trees at Fontainebleau for sheer smell-the-verdure atmosphere. But atmosphere is what the studies of flowers in vases lack. Atmosphere is what Central Park lacks right now, in the antechamber of springtime.

Walking through Central Park after leaving the Met, it was hard not to think of Seneca Village, the settlement of mostly African American New Yorkers that was razed in order to create this leisure space. Public space is never neutral, even when it feels wild and green and free. Every rose bush is a decision, every tree a dedication of resources. For a show full of pretty French flowers, Public Parks, Private Gardens is laudably well aware of its politics. Until New York’s sun comes out, borrow Paris’s.