In 1698, the noted Arabic scholar and

Catholic evangelical crusader, Ludovico Marracci published the first

historically-accurate Latin translation of the Qur’an, as well as a refutation

of the Muslim holy book—both of which he hoped could be used to help “fight

Islam.” Since the Reformations of the sixteenth century, religious conflicts

had been settled not only by the sword, but with the potent weapon of philology,

the linguistic science that produced accurate versions and translations of holy

and ancient texts. Philology had such force that new translations and

interpretations of the Bible had helped split the Church. Marracci hoped that

his accurate work would have the same effect in training crusading priests to

dispute the word of Muhammad.

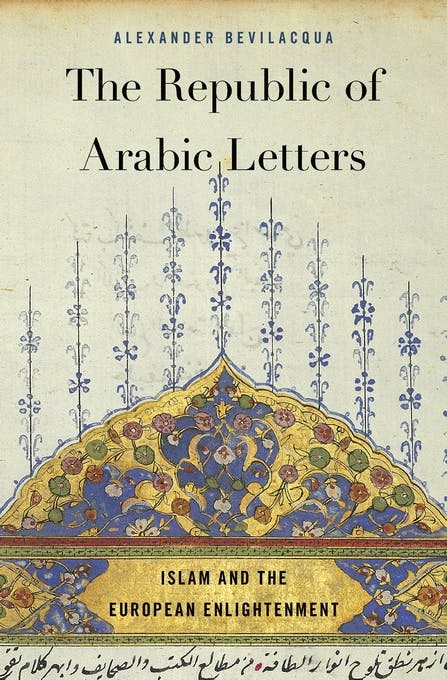

As it happened, Marracci’s translation did not have the effect he intended, as Alexander Bevilacqua shows in his tour-de-force study of the origins of modern Islamic scholarship in the West and its central role in the Enlightenment, The Republic of Arabic Letters Islam and the European Enlightenment. Bible critics and burgeoning Islamic scholars from Paris and Leiden to Oxford used his accurate translation of the Qur’an not to fight Islam, but to study and appreciate it. His work became the basis of even more translations and historical works, ultimately leading to the founding of great schools and centers of Islamic languages and culture in Europe the eighteenth century.

Bevilacqua’s extraordinary book provides the first true glimpse into this story. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Gibbon studied and critiqued Islam along with Christianity, giving the study of Islam a new importance in Europe. The idea that one could equally compare religions was the beginning of a movement of religious tolerance that began with seventeenth-century religious scholars and made its way to the thinking of Voltaire, William Penn and Benjamin Franklin, who believed that Muslim theologians should have the freedom to preach their religion to the citizens of Philadelphia.

What this book shows is that the great philosophes may have been innovative

thinkers, and they took Islam seriously as a religion, but they ultimately

lacked the scholarly skill to excavate Islam in Europe. It was, instead, done

by an often motley group of scholars who fought against remarkable odds to establish

the field of Islamic studies. As we know today, this did not necessarily lead

to a great understanding between religions. The forces of repression were never

far from their scholarship and, contrary to Bevilacqua’s claims, the world of

learning was not always a rosy affair.

Central to Bevilacqua’s story are two friends who began the feat of explaining Islam to Europe in the seventeenth century: Antoine Galland, the Orientalist scholar, book hunter, archeologist and translator of One Thousand and One Nights, and Barthélemy d’Herbelot, the court scholar. Born in 1646 to a modest background, Galland became fluent in Arabic, Persian and Turkish and, at the orders of Louis XIV’s minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, in the 1670s he was attached to the French embassy in Istanbul with the mission of finding rare Oriental manuscripts to send back to the royal collection. Colbert’s goal was not only to create a prestigious library filled with Oriental works, but also to find ammunition in the French crown’s brutal conflict with Protestants and its constant conflicts with the papacy over taxes and jurisdiction.

Galland spent his days scouring Istanbul for literature to legitimate Louis XIV’s religious conflicts and to quench his own thirst for learning. And he loved it, giddily describing the city as brimming over with books “in unbelievable quantity, as much from Egypt, from Syria, from Arabia and Mesopotamia as from Persia itself, where the Turkish armies once advanced considerably.” He succeeded in bringing back the treasures to create the Royal Library’s trove of Oriental manuscripts.

In 1670, d’Herbelot joined Colbert’s team of court scholars. In his famous work Orientalism, Edward Said claimed that d’Herbelot’s work was central in “confirming” to an “insulting” degree the inferiority of Islam for the West. But d’Herbelot’s scholarly feat was far more nuanced. He worked to create an encyclopedia of almost every topic he could find related to Islam, from Muhammad, and the most famous kings of Persia to what he called a “Universal dictionary containing all that pertains to the knowledge of the Peoples of the Orient.” “Princes appear in it, some with their magnificence, their radiance, and their splendor,” Galland wrote of the book, “others with a pure vanity, or a sordid avarice.”

Fluent in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, d’Herbelot included full translated poems and even entertaining and grand mythological tales. He listed all histories, sciences, arts, literary traditions, mythology, magic, and poetry of the Orient, as well as the stories of great military captains. Basing his own work on works such as the sixteenth-century literary scholar Ibn Khatib al-Qāsim’s anthology of Islamic literature, and on the work of the seventeenth-century Ottoman scholar Kātib Çelebi, d’Herbelot attempted to make Islamic scholarship accessible to Europeans. Rather than an attack on Islam—as Marracci had attempted—d’Herbelot’s book was a remarkable tightrope walk between fulfilling the desires of his repressive patrons and creating the most serious European encyclopedia extant of the Islamic world.

D’Herbelot died in 1695, and Galland reworked the Bibliothèque Orientale, publishing it in 1697 with a dedication to Louis XIV in which he says the book will bring “glory” to his reign, while showing how France emulates “the most Powerful Nations of Asia.” Scholars marveled at a book whose contents could be found nowhere else, and was a unique window into the previously unknown Islamic world.

If d’Herbelot was both respectful and

systematic in his treatment of the Islamic world, Enlightenment philosophes were less so. Montesquieu,

the great proponent of mixed government, comparative cultures, and political

liberty, despised the book for what he mistakenly saw as its celebration of “Oriental Despotism.” Ignoring much of what

d’Herbelot had shown—such as Süleyman’s strict following of constitutional

laws—Montesquieu characterized Islamic states as dominated by tyrants and

religiously servile.

It is likely that Montesquieu saw the book’s praise of princes as a way of defending or condoning the despotism of the Louis XIV’s regime. Missing from Bevilacqua’s account is the messy historical background of d’Herbelot and Galland’s work, which he mentions only in passing. Both men knew that they worked for a repressive state; both men had received orders to help find religious justifications for Louis XIV’s massive repression and violent expulsion of French Protestants. They also knew that Colbert destroyed the careers of scholars who were seen as disloyal, and they worked with care to present the Bibliothèque Orientale as fitting in with royal policy and supporting Louis’s glory—which might be a reason d’Herbelot focused so much on the romantic deeds of great princes and poets.

They had made a conscious decision to be complicit in the regime’s religious intolerance. Indeed, other scholars had quit or fled to the freer Holland, rather than collaborate as Galland and d’Herbelot did. In 1685, Louis revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had allowed Protestants to live in peace in France. He demanded that Protestants convert or leave his kingdom under the principle of “Un roi, une foi,”—one king, one faith. To force Protestants to make a choice, Louis billeted undisciplined troops in Protestant houses where they raped, pillaged, tortured, and in some instances even murdered. It was an extensive and effective project of religious cleansing. More than 200,000 Protestants fled France—some estimate the number to be much higher.

D’Herbelot and Galland were certainly aware of the atrocities that their work justified. Galland lived in the house of one of Louis’s worst enforcers, the Intendant Nicolas-Joseph Foucault, who brutalized Protestants by day and supported erudition, Oriental learning and archeology by night. At Colbert’s behest, Foucault had plundered monastic archives and intimidated their librarians. He also reestablished the great Academy of Science, Arts and Letters in Caen and acquired one of the great book collections of the time, including many Oriental works obtained by Galland. D’Herbelot and Galland admired “fair-minded,” “anti-sectarian” scholarship, and yet they sat at the summit of the violence of the 1680s and served its masters.

As Bevilacqua shows in dramatic detail, Voltaire would later defend d’Herbelot’s work against Montesquieu’s attacks. Edward Gibbon, for all his scorn of Islam, recognized the scholarly value of the Bibliothèque Orientale. Major works of comparative religions, such as Bernard Picart and Jean-Frédéric Bernard’s enormously successful set of engravings of The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of All the Peoples in the World (1723-1743), proudly referenced d’Herbelot. And over the eighteenth century, Islamic studies slowly became a major scholarly field. The oldest school of Oriental languages in Europe, “L’Orientale” at the University of Naples still stands in its original buildings, with its famed old library of 60,000 volumes, almost three hundred years after its founding in 1732.

And yet, while the school buzzes with student life during the day, it seems forlorn and disconnected from the great conflicts that have led some to pit notions of Islam and the West against each other. It has taken until now for a book to tell the history of the origins of the Western study of Islam, as Bevilacqua’s does. Few have his linguistic and cultural expertise. He, like the tradition he describes, is a rarity. In spite of the valiant efforts of the great Islamic scholars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, part of their project failed to take hold. This means that the task of Enlightenment is an ongoing struggle, something to value and fight for, even more in times of violence, intolerance and despotism.