Approaching Rajneeshpuram is unlike entering any other American city. Visitors to the embattled mini-metropolis in the arid reaches of central Oregon find themselves subject to constant surveillance, the kind of security precautions normally associated in the United States only with military installations.

As you drive south from Antelope toward Rajneeshpuram, you pass four observation posts, each staffed by two members of the Rajneesh private security team. And that’s before you enter Rajneeshpuram property. The posts, which provide excellent vantage points on the comings and goings on the highway, are located on private land owned by the Rajneeshees, as are seven additional posts located within the city limits of Rajneeshpuram.

The observation posts serve as the tentacles of an extensive, radio-linked security system outlined in confidential Rajneesh security manuals that were obtained by Oregon Magazine and confirmed by the monitoring of the Rajneesh radio system. The security system, which includes more than 150 officers, is intended to observe and record every movement along the only main road linking Rajneeshpuram with the outside world, alerting the Rajneesh command to the presence of anyone perceived as hostile to the group.

The manuals disclose that strangers are first announced as they pass through the town of Antelope, nineteen miles to the north of Rajneeshpuram. Antelope is itself patrolled by the Rajneesh Peace Force (police department) by day and by a private Rajneesh security force by night.

As automobiles pass the first Rajneesh observation post, located four miles from Rajneeshpuram, guards at the post record each vehicle’s license plate and the number of passengers and assign a code to it. Code “Q1” is assigned to those strangers of “questionable intent” and is announced over the “blue” radio channel. “12-28s,” those vehicles deemed “suspicious,” are announced over the red channel. Says the manual: “Red is an emergency channel. . . . ‘O’ is always on red and sometimes monitors all channels.” “O” appears to be the code name for control central.

A special section of the manuals entitled “Bad Guys” lists license plates that should be reported on the red channel. According to the manuals, government inspectors and investigators require special attention, particularly Tom Casey of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. Codes for such government intruders are “9-20” and “9-21.”

Separate pages of the manuals, highlighted in blue and green ink, list special codes and procedures to be used if Casey is seen approaching the ranch. Casey has been investigating the Rajneeshees for more than two years for possible criminal violations of U.S. immigration laws.

At the bottom of one page is the warning: “Better wrong than sorry.”

Overall, the manuals give the distinct impression that the supposedly “open” city of Rajneeshpuram is not very open at all. The manuals state: “Only the Post Office, shops, and restaurants in the Mall and at Buddagosha . . . are open to the public without day passes or armbands.” The road to Rajneeshpuram’s city hall, open to the public on a limited basis during the day, becomes a private road at night, the manuals say.

In fact, most of the city of Rajneeshpuram and all of the unincorporated area of Rancho Rajneesh is private property, and in order to enter those areas visitors must consent to a thorough search. Instructions for such searches read: “Luggage and handbags need to be searched for matches, incense, candles, drugs, firearms, meat, fish, explosive devices, and ranch mail. . . . Ranch mail should be held here to be delivered to Nanak.”

Thinking of vacationing at the ranch hotel? Think twice. The manuals stipulate: “The hotel is open to the public twenty-four hours a day legally. So officially we can’t refuse anyone, sannyasin or not. But non-sannyasins try to discourage . . . say the road is dangerous in the dark, best to go to Madras.”

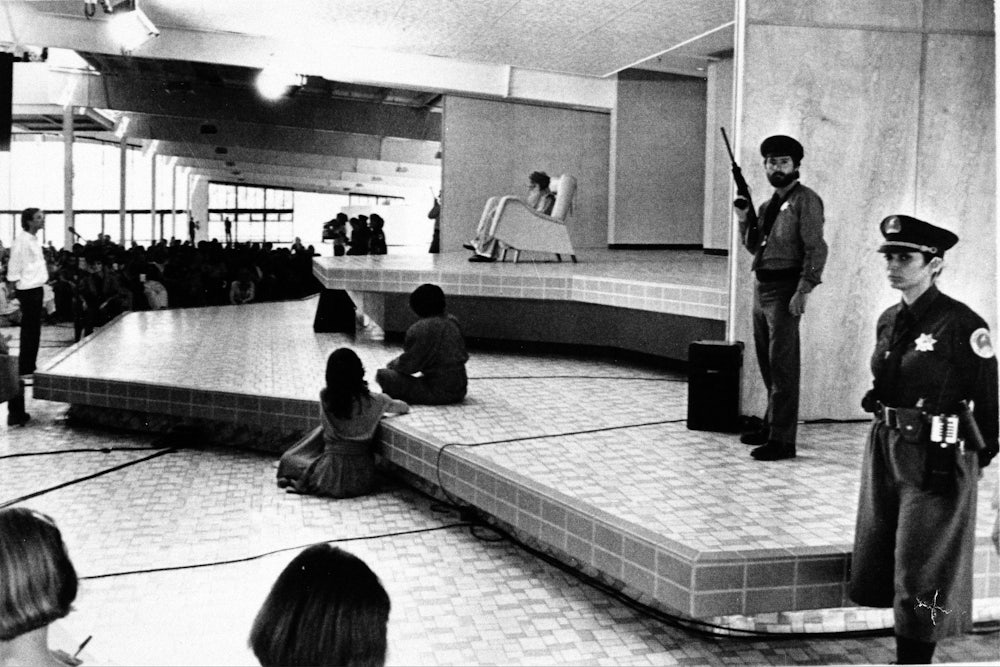

The Rajneesh security forces consist of ten full-time and thirty five part-time police officers. This Rajneesh Peace Force is sanctioned officially by the state of Oregon. The force works in cooperation with a 127-member private Rajneesh security force. These forces are now armed with a variety of weapons, including semiautomatic assault weapons such as CAR-15s and Uzi Model Bs, both of which can be easily converted into fully automatic machine guns.

Rajneesh spokespeople say both the Rajneesh Peace Force and the Rajneesh private security force operate in Antelope because they are needed to protect Rajneesh residents and their property from alleged threats of violence. The Rajneesh Peace Force has been operating in the town since the Rajneesh-dominated Antelope City Council contracted with them for police protection late last fall.

Rajneeshees in private, commune-owned vehicles have patrolled in Antelope since the group first purchased property there in August 1981. From the beginning, pre-Rajneesh Antelopians have complained of the Rajneesh patrols watching them and their houses and photographing them.

Tension in the town between Rajneeshees and non-Rajneeshees escalated last year when former Mayor Margaret Hill and several other non-Rajneesh local residents traveled to Salem for a meeting with Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer. After the meeting, according to non-Rajneesh Antelope residents, the Rajneesh security patrol stationed a manned vehicle outside Hill’s house almost twenty-four hours a day for three months.

On November 1, 1983, local resident Jim Opray picketed the Zorba the Buddha restaurant in Antelope for thirteen straight hours with a sign that read: “UNFAIR TO ANTELOPE RESIDENTS—PATROL CAR HARASSMENT.” Chief Rajneesh attorney Swami Prem Niren threatened Opray with civil legal action. Three weeks after his threat, the Antelope City Council contracted with the Rajneeshpuram Peace Force to provide a one-person, twelve-hour-a-day patrol in Antelope. (The contract has since been amended to provide a two-man patrol.)

Opray frequently picketed in Antelope throughout the first six months of 1984, sometimes joined by other local residents. On June 16, four Rajneeshpuram city police officers entered Opray’s house in Antelope and arrested him. The Oprays recall the officers claimed they had permission from county District Attorney Bernie Smith. They drove Opray to the county jail in The Dalles, seventy-five miles away, and charged him with “menacing.”

District Attorney Smith says that the Rajneesh police had “no authority whatsoever to go into Opray’s house.” He dismissed the Rajneesh police’s charge against Opray, calling it “ridiculous.”

Pre-Rajneesh Antelopians complain of the sizable tax burden that the city council’s contract with the Peace Force has imposed on a town with virtually no history of crime. (Total taxes in Antelope have tripled, to $35–40 per $1000 of assessed valuation, since the Rajneeshees took control of the city council.) Residents also say that the arrest of Opray is only the most blatant example of how the Rajneesh police patrol in Antelope is used to intimidate them.

Says former Mayor Hill: “We live in a police state.”

—Oregon Magazine, September 1984

This article was adapted from The Rajneesh Chronicles, published by Tin House Books.