Over the last two decades, urban architecture has become increasingly unplaceable. As city space gentrifies, downtown business districts—not just in New York or London—are declaring their aspirations of global importance in undulating planes of glass and steel. Whereas the past century saw the construction of stately geometric towers, this new wave of architecture is curved, warped, and fractured, as if squished by invisible pressures beyond our control. A building might resemble the precipitous cliffs of a roller coaster or a billowing sail. The shapes themselves are unique, but the vocabulary is the same around the world; you know it when you see it, though you might not be able to tell exactly where you are. As both symptom and cause of this blandly ubiquitous urbanism, we have in part the architect Bjarke Ingels to thank.

By measure of volume, Ingels is among the most successful architects working today. His firm, Bjarke Ingels Group—or BIG, as it is fittingly spelled and pronounced—currently employs over 400 people on dozens of projects across headquarters in New York, Copenhagen, and London. Among the firm’s many current commissions are campuses for Google in California and London; station and car designs for the Elon Musk–devised Hyperloop; a private school for WeWork; and in Ingels’s hometown of Copenhagen, a power plant that happens to double as an artificial ski slope, opening later this year. Expanding into the business of identities and ideas, in 2016 BIG announced that it would collaborate on a “rebranding” of the entire Nordic region, creating a Monocle-style unified brand for five different countries. He is not just an architect but a global tastemaker.

At 43, Ingels is working at a scale that architects historically don’t reach until their sixties or later, inspiring no small amount of professional jealousy. Equal parts charismatic, obnoxious, and obsequious, Ingels has labeled his work with a series of optimistic catchphrases, including “pragmatic utopianism” and “hedonistic sustainability.” These pass for bold mission statements in an opaque, slow-moving, often publicity-shy industry. “Bjarke is the first major architect who disconnected the profession completely from angst,” Ingels’s onetime boss the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has said, linking him with “the thinkers of Silicon Valley.” A 2012 profile in The New Yorker likened him to a “nightclub DJ” or a “former boy-band star.”

Although Ingels is not yet a household name, his signature blend of aggressive salesmanship and techno-utopianism is set to define the built environment that the rest of us will have to inhabit over the coming decades, as well as the future of architecture firms. If, for the modernist Le Corbusier, houses were to be “machines for living,” in service of their occupants, BIG’s architecture provides the site for something less enduring. Each of his buildings has a signature visual gimmick that plays well on Instagram and on the photo-heavy web sites that make up much of online architecture media. In most major cities the firm has a project or three, suitable for housing metastasizing start-up offices, their employees, and floating cultural elites—buildings that are specific without being local, existing within cities but not of them.

If all his plans go ahead, Ingels could leave as great an imprint on the world’s wealthiest cities as any architect alive today. The result will be a kind of aggregate BIG world, in which rapid change and flexibility take precedence over a textured sense of place and community, as architecture merges with brand building. How, at a time when diverse cities are more vital than ever, did we get here?

The craft of architecture is still passed from master to pupil, as younger architects work under the founders of larger firms. Thus the story of BIG starts with the first generation of “starchitects,” a term coined by Los Angeles journalists and in widespread use by the time House & Garden deployed it in 1988. The portmanteau referred to a group of celebrity architects who built in signature styles, including the British Norman Foster, Michael Graves, Richard Meier, and most famously, Frank Gehry, who founded his practice in Los Angeles in 1962.

Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao, the instantly iconic art museum formed by sweeping, curvilinear slashes of titanium facade, opened in 1997. Increased tourism to Bilbao and the incubation of a newly active cultural scene around the museum established the “Bilbao effect”: the way that dramatic (even unwieldy) buildings, designed by international starchitects, could create economic stimulus. Statement architecture proved to be a profitable investment; Bilbao launched a kind of arms race, with cities commissioning increasingly elaborate structures in attempts to grab attention. In turn, architects became public pop-intellectuals, each stuck in a personal stylistic mode, promoting their services to global client lists.

While their individual styles vary significantly, the starchitects tend to fall into two broad groups. There is the sprawling and corporate Dark Side, totalitarian-leaning in aesthetic: Foster + Partners, the late Zaha Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, and Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Think of the infinite-loop CCTV tower in Beijing or 56 Leonard, the Jenga-like tower new to the New York City skyline. The contrasting Light Side is smaller-scale and integrity-minded, with a classical philosophical bent, if not always business-savvy: the likes of Steven Holl, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (of the upcoming Obama Presidential Center), Renzo Piano, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro (of High Line fame). Ingels mixes the scale and vision of the first group with the aesthetic accessibility of the second. He’s less invested in ideology than in attaining an air of profitable idealism.

The unique buildings that starchitects produce often set themselves apart from the fabric of their locations—amid a neighborhood of brick town houses there will suddenly appear, for instance, a silver blob like the ovoid spaceship from Arrival. This element of disjunction has become a cliché of postmodern architecture. In his 1991 study, Postmodernism, the theorist Fredric Jameson observed that architect John Portman’s cavernous Bonaventure Hotel in LA aspired to be a “complete world, a kind of miniature city.” Rather than fitting into a city as one of its organic parts, the building wished to be “rather its equivalent and replacement or substitute.”

This strategy continues to define architecture today, particularly in BIG’s self-sufficient, self-sustaining work. BIG’s King Street West development in Toronto is one such miniature city, a compound that combines heritage buildings and new retail and office space with a canopy of boxlike apartments. BIG designs tend to form closed loops; one can easily imagine never leaving King Street West, though it’s possible to walk through its courtyard to other blocks.

The first starchitects traded in buildings that acted as symbols for specific places, at a time when cities were competing for visibility as well as capital on a global scale. The competition has intensified with the rise of the internet and the rebirth and globalization of Silicon Valley in the 2000s. Now Ingels and BIG are emblematic of an age in which every building must be a signature unto itself, acting as a branded digital image to spread online and as a proof of concept for the Bilbao effect—and, last of all, a physical space to inhabit.

Of the previous starchitect generation, Rem Koolhaas may have had the greatest influence on BIG’s practice. In 1993, Ingels enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts to study architecture. (He’d wanted to be a cartoonist and thought the program would improve his drawing skills.) There, Ingels found himself drawn to Koolhaas’s early conceptual projects—such as a design for a French national library in Paris formed of a three-dimensional grid shot through with sculptural voids—and in 1998, he began working at OMA. In the ’90s, Koolhaas’s firm perfected a workflow referred to as “brute force”: Throw as many designers as possible at a project and make an infinity of models; if you create all possible solutions, one has to be the best. Brute force is now standard for larger firms. “The dominant story of the last 20 years of architecture has been one of OMA-ification,” the architect Bryan Boyer wrote in 2012. The system creates the unique, intellectualized forms for which OMA is known but also results in a legendarily harsh 24-7 work environment. New employees suffer through a few years then leave ready to go independent (a reputation BIG has gained as well).

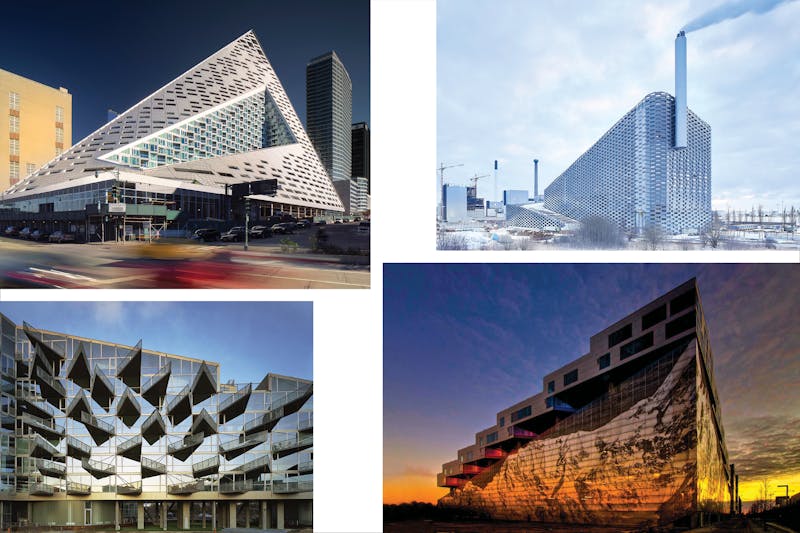

Having passed through the machine, Ingels left in 2000 to start an architecture studio, PLOT, in Copenhagen with his OMA colleague Julien De Smedt. PLOT’s major work, which presages BIG’s approach, is the VM Houses in the recently developed Ørestad district of Copenhagen. The two residential structures are in the shape of the letters V and M, with apartments running all the way through the arms of the buildings for light, and jagged, wedge-shaped balconies jutting out from the walls like spikes. The buildings don’t look like anything around them, but then there’s nothing around them except highways and small homes. Most importantly, the young firm was willing to be flexible on materials and approach to finish on time and budget. Ingels ended up living in one of the apartments.

He struck off on his own with BIG in 2005. The Mountain, the firm’s first landmark, is situated next door to VM. It’s an angular form like the slope of a mountain, terraced by boxy apartments, each with its own garden; the inside of the mountain holds a parking garage. The building suggests that architecture can give you everything at once: an individualized suburban living experience with the efficient density of a city and the epic scenery of a vast landscape, your car still just an elevator ride away. After it was completed in 2008, Ingels once again moved in.

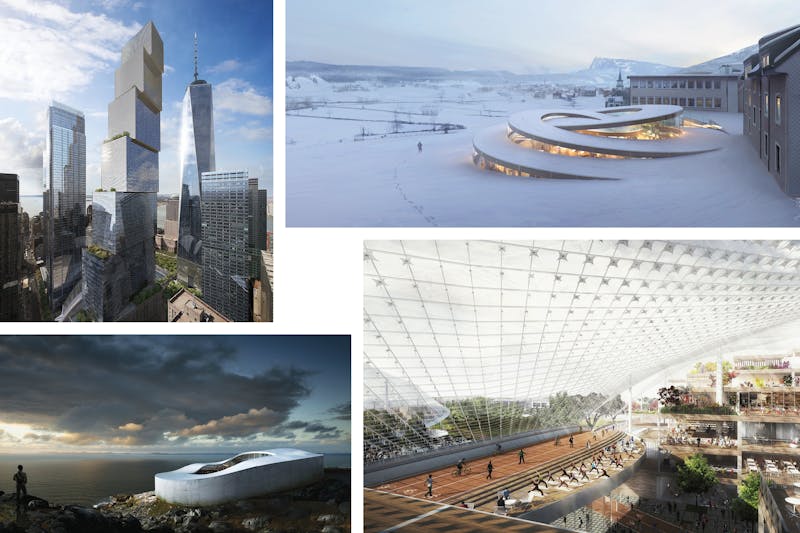

In 2009, BIG released a manifesto titled Yes Is More, riffing on Mies van der Rohe’s signature aphorism “less is more.” The book, presented as a graphic novel, documents the firm’s work, including multipeak mountainous complexes in Azerbaijan; the morphing, Hadid-like World Trade Center in Vilnius, Lithuania; and the torqued skyscraper Escher Tower for a Norwegian hotel developer, which weaves three monoliths into one. Like the VM Houses, each design has its own gimmick, a one-liner of architecture. “What if design could be the opposite of politics?” the book optimistically proposes. “Rather than revolution, we are interested in evolution.”

BIG’s signature work followed, propelling the firm to prominence. Its Danish Pavilion for the Shanghai World Expo 2010 was a single gestural swirl that integrated a bike path (the gimmick) with shared bikes donated to the city afterward. That year, BIG also won the commission for Via 57 West, a pyramidal residential building on Manhattan’s far West Side developed by Douglas Durst and completed in 2016. In Big Time, a new documentary by the Danish director Kaspar Astrup Schröder, Ingels refers to it as a “Courtscraper,” since the center of the pyramid is left open for a planted courtyard that Ingels likens to a private Central Park (the gimmick). “Bjarke does not have a fragile ego,” Durst says to Schröder’s camera. “We’ve had architects who simply refuse to take direction.” Presumably, they didn’t last long.

In order to execute Via 57 West, BIG opened a second headquarters in New York that rapidly expanded to 150 staff. Brute force requires manpower, and as the firm grew, it also had to win more projects to sustain itself. A crisis moment occurs, the documentary shows, when the firm isn’t getting as many commissions as it needs. The conclusion seems to be that Ingels himself—the charismatic figurehead clients got sold on—needed to be more present in the pitching process rather than leaving the day-to-day creative management of the firm to his partners as he jetted between offices. (A concussion also knocked Ingels out while the documentary was being filmed, but he recovered without significant injury.) The personality is the product.

BIG is as much a brand as an architectural practice, devoted less to building timeless structures than to associating itself with the newest and latest. This might explain why Silicon Valley clients like Google and WeWork find Ingels’s sensibility so appealing. Like a good start-up, BIG is scalable and self-replicating; the bigger it gets, the more it can grow and the more arenas it can enter.

Its design for the WeWork school, WeGrow, which is set to open in Chelsea this year, is a template interior that, like the start-up’s co-working spaces, can be replicated anywhere. It features modular classrooms, “digital portals,” ovular cutout windows, and a mesh spiral staircase rising through a “vertical farm” of planters on shelves. The firm continues its habit of glibly unifying opposites in its description of “a learning landscape that’s dense and rational—yet free and fluid.” WeGrow’s architecture poses education as a boutique, on-demand service rather than a permanent and equitable institution, built on community and an ideal of the public good.

“Free and fluid” could describe BIG’s initial designs (with another young architect, Thomas Heatherwick) for a Google headquarters in Mountain View, California. More extreme than Gehry’s industrial-chic Facebook headquarters or Foster’s flying saucer for Apple, the complex was to be utterly utopian, a giant translucent canopy under which a kind of Google city would bloom. The interior structures beneath the bubble would be modular and could be rearranged by crane-robots according to the needs of company projects—kind of the ultimate open office. But it wasn’t to be: Google didn’t get the land it wanted, and instead the architects pared their plans back to a more traditional pagoda-ish, vaguely fungal megastructure. In the latest renderings, no canopies or crane-robots are referenced.

The perfect merging of BIG’s concerns with those of Silicon Valley might be its designs for the Hyperloop—a hypothetical transportation method that involves carriages speeding through a low-pressure tube. Elon Musk open-sourced the concept’s technology so anyone could run with it. Virgin Hyperloop One is one such company, currently working with the city of Dubai to carry out research. For Dubai, BIG designed a floating, airportlike Hyperloop station made of warm wood and glass that arcs out in two semicircles with small ports for each car-pod, which band together into cylindrical carriages. The carriages are shot through raised metal tubes across the landscape at over 1,000 kilometers an hour, arriving at another spacious, gleaming circular depot like something out of a Blade Runner sequel directed by Steve Jobs.

Everything in the hypothetical project is about extreme speed, so carefully managed as to be unnoticeable. The aim of the Hyperloop is to make travel so fast that geography becomes irrelevant—“physical distances are virtually eliminated,” as one BIG partner put it. This is emphasized by BIG’s design, as well as its practice as a whole—a sort of architecture for placelessness.

“Yes is more” means that Ingels is building as much he can, as quickly as possible. As he muses in the documentary, “You only get 20 or 40 buildings before your time is up.” Even the wunderkind of architecture feels the pressure to leave a mark.

Ingels is already superseding his starchitect predecessors in some ways. In 2015, BIG’s design replaced Norman Foster’s for 2 World Trade Center, in part at the preference of James Murdoch, whose family’s companies 21st Century Fox and News Corp were going to be the anchor tenants. Foster’s design was a quartet of stately towers topped by diamond-shaped slices tilting toward the sky, a dramatic addition to the site and a gesture toward the angular monolith of David Childs’s 1 WTC. BIG’s contribution is, instead, an ungainly series of seven boxes (meant to echo the low-rise buildings of TriBeCa), each shifted off-center, with gardens and tickers on the exposed edges.

Yet BIG’s neato gestures are often rejected in public. In 2011, it released a redesign plan for the Kimball Art Center in Park City, Utah, a twisting log-cabin-style structure (referencing the mining town’s history) that was criticized for its height. In 2014, a second design with an angular facade like DS+R’s Lincoln Center was shot down for not being historical enough. Eventually, the plan was abandoned and the Kimball building was sold to developers. In 2016, BIG’s master plan for the Smithsonian, which proposed demolishing a traditional public garden in favor of an underground gallery complex with upturned glassy corners, also attracted controversy, prompting a redesign, released early this year. A snappy image can get a project green-lit, but it doesn’t mean the design will survive into reality.

These buildings benefit the BIG brand, even when they don’t get built—as long as the viral renderings attract more fans and followers. The firm can sell design products, creative direction, or furniture instead of architecture. In 2009, Ingels co-founded KiBiSi, a collaborative industrial-design studio that has worked on projects like minimalist wristwatches, a streamlined electric bike, and a chair in the shape of Via 57 West. More recently, he launched BIG Ideas as an incubator for devices like smart door locks as well as services like in-house data crunching. Inside the firm, a new strategy has emerged: For every project, there should be a product. In this way, the auteur phase of starchitecture has ended with a whimper, as its leading figure presents an array of consumer experiences and corporate consulting under the thin guise of a singular vision.

You can live in a BIG tower, work in a BIG office, send your kids to a BIG school, tell the time by a BIG watch, sit in a BIG chair, ride a BIG bike, and stream a film about BIG on Netflix. And yet the end result of this omnipresence is a kind of absence, as unique places—the heterogeneous fabric of cities, designed by no single architect, the organic sites of our lives—lose their meaning and purpose. We might be comforted by the possibility that such a self-contained ecosystem of generic buildings, isolated from their landscapes, can without much hassle or nostalgia be knocked down or reconfigured for whatever comes next.