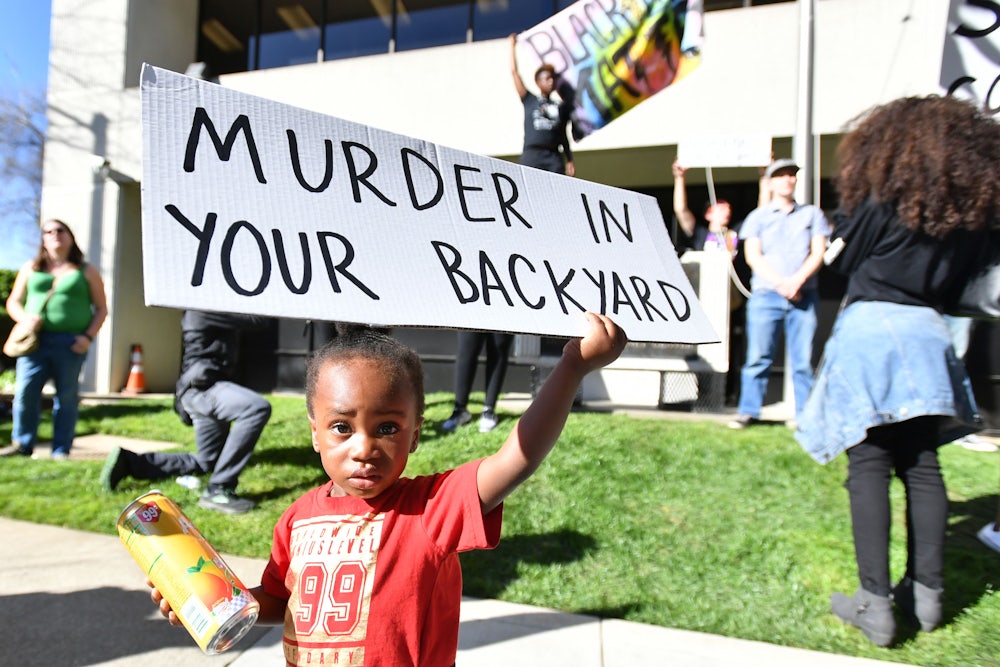

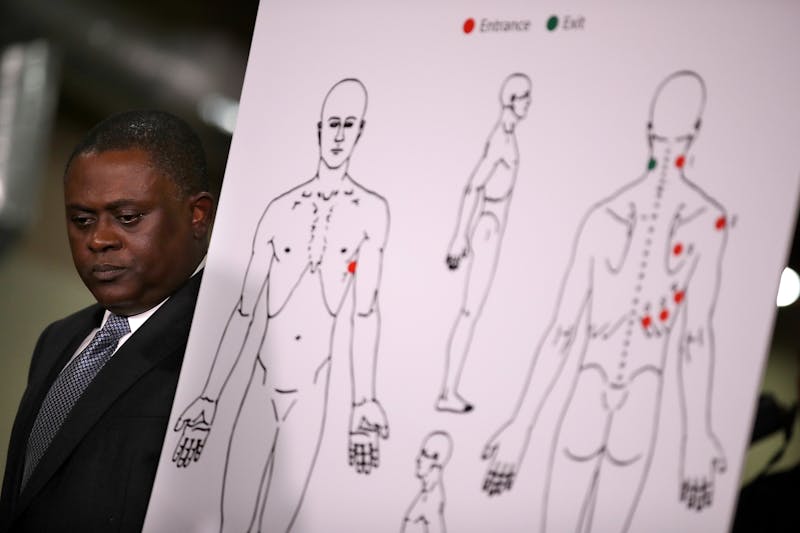

Stephon Clark’s encounter with Sacramento police officers two weeks ago lasted only about 20 seconds. Body-camera footage shows a frantic, tense scene: near-total darkness, a brief chase into a backyard, the overlapping din of officers’ barked instructions. Neither of the two cops identifies themselves as police, even as one of them shouts, “Show me your hands! Gun, gun, gun” Then they open fire on the 22-year-old man.

Clark did not have a gun. He died in his own backyard.

In its initial statement, Sacramento police said “the suspect turned and advanced towards the officers while holding an object which was extended in front of him. The officers believed the suspect was pointing a firearm at them. Fearing for their safety, the officers fired their duty weapons striking the suspect multiple times.”

Legally, this justification for deadly police shootings—that the cops’ feared for their safety—has consistently passed muster, in California and elsewhere. But in the wake of Clark’s death, which has sparked protests in Sacramento, state Democratic lawmakers have proposed major legislation to curtail such broad discretion for police. If the Police Accountability and Community Protection Act becomes law, it would be the first of its kind to raise the legal threshold for when officers can use deadly force and require police to use non-lethal options first. The American Civil Liberties Union and groups aligned with the Black Lives Matter movement support the legislation.

While a few states, such as Delaware and Tennessee, only allow officers to use deadly force “if all other reasonable means of apprehension have been exhausted,” most states only require that the use of force be “objectively reasonable,” a legal standard articulated by the Supreme Court in the 1989 case Graham v. Connor. That threshold almost always benefits the police, since judges and juries tend to be extremely deferential when assessing whether an officer was acting reasonably in the heat of the moment.

California’s current law on use of force dates back to 1872 and allows “all necessary means to effect the arrest,” although the state uses the Graham “reasonableness” standard in practice. The “necessity” standard being proposed by California lawmakers would rework that legal calculus to be less deferential, only allowing officers to use deadly force to prevent imminent physical injury. Otherwise, police would be required to use verbal warnings, Tasers, and other de-escalation tactics to defuse a situation before resorting to more lethal methods.

“We’re not saying officers can never use deadly force. I want to stress that,” Assemblywoman Shirley Weber, who co-wrote the proposed legislation, told reporters at a press conference on Tuesday. “Deadly force can be used, but only when it is completely necessary.”

The necessity requirement would be a major departure from American police practice, which typically defers to officers’ judgment in volatile situations. “Under the current standard, if there’s a threat, an officer can use deadly force even if there were alternatives to using deadly force,” Lizzie Buchen, a legislative advocate at the ACLU of California, told me. “This would shift [the legal standard] so that if an officer’s feeling a threat, and there are alternatives to deadly use of force, then they need to use those first.”

Unlike standards in Delaware and Tennessee, the legislation would also take into account whether officers placed themselves in unjustified danger before using deadly force. “Under current law, if an officer jumps in front of a moving vehicle, they can legally kill the driver because now they’re suddenly in harm’s way,” Buchen explained. “What this law would say is that that officer needs to be held accountable for creating the necessity of killing the driver.”

The Supreme Court often gives American police officers broad leeway in determining when they can use lethal force in civil lawsuits, although states can set even higher legal standards in criminal cases. The high court first addressed the issue in Tennessee v. Garner in 1985. The case arose from the 1974 death of Edward Garner, a 15-year-old black teenager who allegedly broke into a Memphis home and stole a wallet containing $10. A local police officer called by neighbors found Garner behind the house, who then tried to flee by jumping over a six-foot fence. The officer ordered him to halt and then shot Garner in the back of the head.

The justices ruled that the officer had gone too far. “It is no doubt unfortunate when a suspect who is in sight escapes, but the fact that the police arrive a little late or are a little slower afoot does not always justify killing the suspect,” Justice Byron White wrote for the court. “A police officer may not seize an unarmed, non-dangerous suspect by shooting him dead.” However, the justices left the door open to using lethal force if the officer believed the suspect would pose a threat to others.

Upon revisiting the issue in Graham, in 1989, the Supreme Court established what’s known as the “objective reasonableness” standard when weighing excessive-force claims. The justices rejected tests of intent or malice to assess whether an officer’s actions violated the Fourth Amendment, arguing they were too subjective. Instead, they established a high threshold for civil lawsuits by placing great value on an officer’s instincts in the heat of the moment.

“The calculus of reasonableness must embody allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving—about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation,” Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote for the majority.

Graham dealt with civil lawsuits against officers, but most states have also adopted the “objectively reasonable” standard for criminal prosecutions. The phrase rose to prominence after the 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson. A grand jury declined to indict Wilson, and a year after the killing, the Justice Department concluded that the multiple shots Wilson fired “were not objectively unreasonable uses of force” under federal law.

A Cleveland grand jury also declined to indict a white police officer who had fatally shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice in a public park in 2015. Rice had been playing with a toy gun when the officer and his partner pulled up and shot him within a few seconds. Prosecutors gave jurors a report prepared by independent experts that concluded “that Officer [Timothy] Loehmann’s belief that Rice posed a threat of serious physical harm or death was objectively reasonable as was his response to that perceived threat.”

In the summer of 2016, a 911 caller in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, claimed he had been threatened by a man selling CDs outside a convenience store. Two officers arrived, found 37-year-old Alton Sterling selling CDs outside, and shot and killed him after a brief struggle during a 90-second encounter. Body-cam footage from one of the officers doesn’t provide a clear visual account of what happened, but the audio captures Sterling asking “what did I do?” as officers scream instructions at him.

Louisiana prosecutors ultimately declined to prosecute the officers. The Justice Department also closed its investigation without bringing civil-rights charges, citing the “objectively reasonable” standard and the legal threshold to prove intent. “It is not enough to show that the officer made a mistake, acted negligently, acted by accident or mistake, or even exercised bad judgment,” the department concluded in 2017. “Although Sterling’s death is tragic, the evidence does not meet these substantial evidentiary requirements.”

California’s proposed bill stands a chance of becoming law, as the state legislature and governor’s office are both controlled by Democrats. But the legislation will meet stiff resistance from police unions, which traditionally resist stricter controls on when their members can use force against suspects. Craig Lally, a union president for rank-and-file cops in Los Angeles, told the Los Angeles Times that the bill “will either get cops killed or allow criminals to terrorize our streets unchecked.”

California is often a national leader in progressive legislation, so it’s not hard to imagine that successful implementation there could inspire Democratic-led legislatures in other states to consider a “necessity” threshold. Changing legal standards like these would also alter how police departments handle disciplinary complaints and training for new officers, effectively transforming California into something of an experiment for a new way of policing.

“This would certainly be unique,” Buchen said. “There’s no other state that has a state law with this kind of protection for civilians.”