The so-called war on science isn’t quite as broad as that phrase implies. It’s really a war on one particular scientific fact: that fossil fuels are a threat to public health.

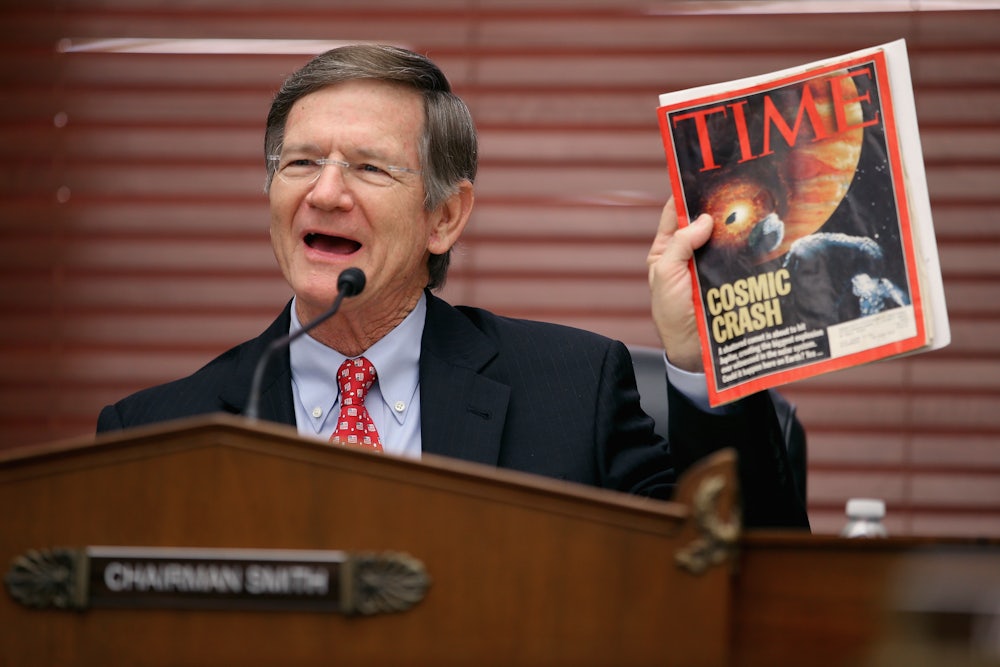

Countless Republicans have waged this war over the last decade, but its battle strategy was the brainchild of one man: Lamar Smith. Like many of his peers in the GOP, the Texas congressman has long distrusted the scientific evidence that humans are causing climate change. And ever since he became chairman of the House Science Committee in 2013, he’s used his position to try to undermine that science, as well as the science behind air pollution—namely by pushing two bills that would radically change how the Environmental Protection Agency is allowed to use science and receive scientific advice to craft regulations.

Though routinely passed by the Republican-controlled House in recent years, these bills have proven too extreme for passage the Senate, at least thus far. And yet, when Smith retires next year after 31 years in Congress, he will do so knowing that his goals have been achieved—even if the bills themselves never become law. Those goals were not merely to undermine climate and air pollution science in the public eye, but to ensure that science cannot influence public policy. Barely more than a year into the Trump administration, Smith and the Republicans have won the war on science.

The most consequential sign of Smith’s victory came last month, when EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt sat down with a reporter for the conservative Daily Caller News Foundation* to announce significant changes to the way the agency uses science. No longer would the EPA use scientific research that includes confidential data to develop rules intended to protect human health and the environment. “We need to make sure their data and methodology are published as part of the record,” Pruitt said. “Otherwise, it’s not transparent. It’s not objectively measured, and that’s important.”

This new policy is a near carbon-copy of Smith’s Honest and Open New EPA Science Treatment Act, or HONEST Act, and might seem reasonable on its face. (Who doesn’t want more government transparency?) But the policy, which is opposed by most scientists and non-profit scientific societies, will force the EPA to ignore most of the research showing air pollution can cause premature deaths (including a landmark MIT study in 2013 that found air pollution causes about 200,000 early deaths each year). That’s because the bulk of the peer-reviewed literature on effects of fine particulate matter and other pollutants is based on confidential data: human medical records, which are protected by federal law. Though hundreds of scientists have approved these studies through extensive peer review, Pruitt says the results aren’t reliable because some of the information isn’t publicly verifiable.

When Pruitt implements this policy, he’ll be disqualifying “the main body of science that EPA has historically used” to justify limiting air pollutants, said David Baron, the managing attorney for Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization. That body of science, for instance, supports the Mercury and Air Toxics Standard, which restricts the amount of mercury and other heavy metals that coal plants can emit. It also supports the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which control emissions of soot, ozone, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and lead. And the Clean Power Plan, Obama’s signature regulation to curb greenhouse gas emissions, is backed by science about the health impacts of particulate matter.

The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to regulate all the pollutants these rules cover, but only to the exposure level that scientific literature says is safe for humans. If that literature is effectively erased from the agency because it’s based on confidential data, representatives for polluting industries can more confidently challenge the rules in federal court. But it also gives Pruitt the necessary legal cover to weaken those rules himself, which he has said he intends to do. Though Pruitt’s plan has not yet been implemented, Baron says its eventual impact cannot be overstated. “It’s going to make it extremely difficult for EPA to do its job of protecting people from dangerous air pollutants,” he said.

Pruitt isn’t just trying to disqualify inconvenient scientific literature, but scientists themselves. In October, he banned scientists who have received EPA money from advising him on environmental policy. This is another brainchild of Smith: His Science Advisory Board (SAB) Reform Act is based on the presumption that environmental scientists who have received money from the EPA for research—as many of them have—are biased in favor of regulation. Pruitt agreed. He has also appointed industry representatives and red-state government officials to his Science Advisory Board, even though industry representatives are likely biased against regulation and state governments receive money from the EPA. Many of Pruitt’s new scientific advisers don’t accept climate or air pollution science.

Joe Arvai, a University of Michigan professor who served as an EPA science advisor until his six-year term expired in late September, said this restructuring has already had chilling effects. During his tenure, he said, career EPA employees in the Office of Water and Office of Air would routinely ask the EPA administrator for advice from his Science Advisory Board. “Those career staffers aren’t doing that anymore because they’re fearful for what kind of hatchet job the SAB might do,” he said. Despite his aggressive rollback of regulations, Pruitt doesn’t appear to be asking much of his science advisors, as the SAB hasn’t issued any reports in 2018. There were 10 SAB reports issued 2017, but Arvai said “they’re all just carry-overs” of requests made before Pruitt arrived. Under the Obama administration, the SAB averaged about 11 reports per year.

Though Smith knew these policies were essential to preventing science from influencing public policy, he also knew the power of public opinion. Deemed the “most obnoxious climate denier in Congress” by one Los Angeles Times columnist, Smith worked for years to promote bogus scandals against climate scientists and discredit the field. The Trump administration also appears to be trying to influence public opinion by deleting “climate change” from government documents and replacing it with phrases like “weather extremes.”

An investigation published Monday by Reveal shows just how far the Trump administration will go to deny climate change. The Interior Department delayed the release of an 87-page report on flooding risks in U.S. national parks for 10 months, for the sole purpose of deleting every mention of the phrase. Doing so “prevented park managers from having access to the best data in situations such as reacting to hurricane forecasts, safeguarding artifacts from floodwaters or deciding where to locate new buildings,” according to the article, and critics decried the delay as an “unprecedented political interference in government science.”

Such interference has proven common for the Trump administration, and it appears to be influencing scientists and members of the voting public. Late last year, NPR released data showing that many researchers are now avoiding the phrase “climate change” in grant proposals to the National Science Foundation, the independent government agency that funds the bulk of U.S. research. And last week, a Gallup poll found that the percentage of independent voters who “believe global warming is caused by human activities” fell to 62 percent in 2018, and 8-point drop from last year. Only 35 percent of Republicans believe likewise, compared to 40 percent in 2017.

On the left, the opposite is happening. In the Trump era, Democrats are increasingly accepting the scientific consensus that humans are causing climate change. The issue is also rising on the priority list for Democrats: A recent Harvard University poll showed climate change ranked alongside healthcare and Russia as the top tissues motivating Democratic voters in 2018. This suggests the party could mobilize its supporters by developing and championing an aggressive climate and air pollution policy platform, which it has failed to do so far.

Even with a Democratic wave in 2018, reversing the damage done by the Trump administration will prove difficult for as long as he’s president. That’s why environmentalists are putting their hopes in the legal system—but also fearing the worst. If the courts uphold the EPA’s rationale for repealing and replacing pollution regulations, “it could be devastating,” Baron said. The impacts of even a few years of weakened air pollution regulations would fall disproportionately on low-income and minority communities, leading to premature deaths—at least according to the scientific literature that Pruitt wants the EPA to ignore.

What is clear is that the war on science has been won, and its opponents must now wage a war of their own. They need their own Lamar Smith.

*This article originally stated that Scott Pruitt was interviewed last month by a reporter for the conservative website The Daily Caller. He was interviewed by a reporter for The Daily Caller News Foundation, a nonprofit news organization closely associated with the for-profit Daily Caller.