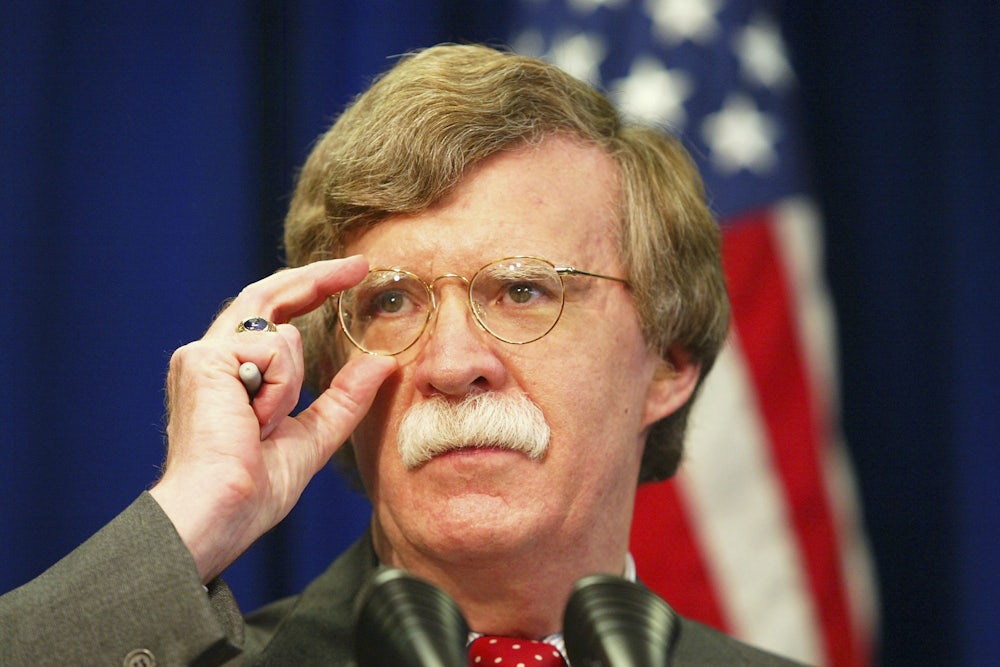

What’s so rude about Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security John Bolton? Iran’s Foreign Ministry has called Bolton “rude” and “undiplomatic.” North Korea has called Bolton “rude,” too—not to mention “human scum,” “an animal running about recklessly,” and “an ugly fellow who cannot be regarded as a human being.” Then there is Terre Cass, a court administrator in Florida, where, during the 2000 Bush-Gore recount, Bolton and his signature Easy Rider mustache became a media icon. Cass said Bolton, who spent his days sandwiched between members of the Palm Beach County Canvassing Board inspecting chads for the Bush team, “was very rude.”

But rudeness—or, as Bolton’s supporters prefer, bluntness—has its uses. Upon his arrival in Florida, Bolton reportedly barked, “I’m with the Bush-Cheney team, and I’m here to stop the count.” When he did exactly that, a grateful Dick Cheney told an audience at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) that Bolton’s job in the new administration should be “anything he wants.” Indeed, no sooner had Bolton finished accomplishing his aims in Boca Raton than he was rewarded with a high-ranking State position and set about accomplishing his aims on the international scene. Before long, he had engineered America’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, established a harder line against North Korea and Iran, scuttled a draft protocol on enforcing the Biological Weapons Convention, waged a successful campaign to oust the chief of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, and set the stage for America’s abandonment of the International Criminal Court (ICC). And that was only year one.

The secret to Bolton’s record is that, in a foreign policy team divided roughly between ideologues with no managerial skills and managerial types with no ideas, Bolton is that rare commodity: an operator and an ideologue. Bolton the operator is the man charged by Senator Joe Biden with being “too competent,” a man who supposedly snacks on foreign service officers, lectures diplomats on their irrelevance, and clocks more travel miles than any of his peers. Bolton the ideologue is the man whose office walls are lined with inscribed photographs of conservative luminaries, who operates, according to New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, as “the neocons’ man at State.” The portrait gets Bolton half right. Bolton surely qualifies as a conservative--just not the kind Krugman has in mind. If anything, in fact, Bolton amounts to a walking repudiation of neoconservatism. Which helps explain why he has accomplished more than anyone else on Bush’s foreign policy team.

As former liberals whose democratic idealism still infuses their views of the world, neoconservatives routinely find themselves charged with being the heirs of Woodrow Wilson’s “crusading” foreign policy style. No one has ever applied the adjective “Wilsonian” to John Bolton. And, as anyone who bears the slightest familiarity with Bolton’s catalogue of speeches and writings will tell you, there is nothing remotely “neo” about him. Rather than echoes of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, one hears from Bolton echoes of the postwar conservatism of the early National Review, of Barry Goldwater (who Bolton campaigned for), of Jesse Helms—who once boasted, “John Bolton is the kind of man with whom I would stand at Armageddon.”

Testimonials such as these prompt his detractors to accuse Bolton of practicing, in the words of The Nation’s Ian Williams, “diplomatic redneckery.” That is one way of putting it. Realism is another. Yet, unlike earlier devotees of realpolitik—such as Reinhold Niebuhr, who complained that the United States was “still inclined to pretend that our power is exercised by a peculiarly virtuous nation”—Bolton’s is a fiercely nationalistic brand of realism. “I am pro-American,” Bolton has said. “That means defending American interests as vigorously as possible and seeing yourself as an advocate for the U.S. rather than as a guardian of the world itself.” Like his neoconservative counterparts at the Pentagon, he believes that, absent the robust assertion of U.S. power, a fundamentally Hobbesian international scene will erode. Unlike them, he does not believe the spread of American ideals can ameliorate this condition. This, needless to say, makes his job much easier.

Idealism may be a spur to reason, but, in a world that in recent years has allowed for the assertion of America’s geopolitical weight but that has also greeted its attempt to promote universal ideals as “delusional” (in the words of Egyptian autocrat Hosni Mubarak), Bolton’s preference for an “interests-based foreign policy grounded in a concrete agenda of protecting particular peoples and territories” has proved much simpler to accomplish. Involving a sense of limits, such interests have certainly been more easily achieved than the Bush administration’s avowed aim of a “global democratic revolution.” Rather than the construction of a new world order, after all, a vision like Bolton’s merely requires tearing down the old.

This happens to be his specialty. With Bolton at the helm, Senator Byron Dorgan warned, the United States would “abandon ABM, ... build a destabilizing national missile defense system, abandon the Kyoto treaty, suspend missile talks with North Korea, [and] oppose the International Criminal Court.” He was right. The first element to go was a proposal to regulate the trade in small arms, made at a U.N. conference in the summer of 2001, which Bolton effectively torpedoed by invoking America’s “cultural tradition of hunting and sport shooting.” Then came a U.N. proposal to enforce the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, which Bolton also scuttled on grounds of national sovereignty. Finally, Bolton’s campaign to apply “a bottle of Wite-Out” to America’s signature on the treaty establishing the ICC culminated in the White House doing just that. Though technically it fell outside his jurisdiction, once the decision had been made to blot out the treaty, Bolton’s was the signature affixed to the letter informing Kofi Annan of the news. It was, Bolton told The Wall Street Journal, “the happiest moment of my life.”

Few thought the moment would last, yet the international community hasn’t been able to stop Bolton from chipping away at its foundations. Intelligence cables, for example, reveal foreign officials complaining bitterly about Bolton, yet, at the end of the day, the very same officials have ended up embracing his proposals. The orchestration of America’s withdrawal from the ABM treaty offers a case in point. When Bolton informed his Russian counterparts that he didn’t view the treaty as a “permanent” accord and that the United States could withdraw from the agreement anytime it wished, “the arms control guys in the room looked like they were going to pass out,” says a member of the negotiating team. The fact remains, however, that ABM defenders had argued for years that, were the United States to abandon the treaty, a new arms race would ensue. Yet the truth turned out to be exactly the reverse: Rather than build up their arsenal in the aftermath of the U.S. decision, the Russians pledged to slash it dramatically under the terms of a treaty Bolton hammered out with Moscow.

The major efforts to stop Bolton, in fact, come mostly from within his own building. This is nothing new. As chief of the Reagan Justice Department’s Civil Division, Bolton’s run-ins with the bureaucracy prompted Patricia Schroeder to liken him to Captain Queeg. As an assistant secretary of state during the first Bush administration, Bolton ruffled pinstripes at Foggy Bottom when the administration sent him—over the head of U.N. Ambassador Thomas Pickering, a career diplomat the Bushies never fully trusted—to the U.N. Security Council, where he blunted an anti-Israel resolution in the works. Today, too, foreign service officers carp about Bolton the “anti-diplomat.” During his 8:15 a.m. meetings with the assistant secretaries of state who report to him, for instance, the bureau chiefs stand the entire time, an indignity that has become part of Foggy Bottom mythology. Bolton’s appetite for intelligence reports has led to run-ins with State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, whose staffers object to what they see as his back channels to the CIA. He has clashed repeatedly with the Bureau of Nonproliferation, the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, and the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs. Bolton’s aides, too—all but one of them political appointees and several recruited from AEI—have stirred resentment in the diplomatic ranks. The State Department’s Near East hands, for example, grew so exasperated with Bolton’s Middle East point man, David Wurmser, that they complained to Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage and henceforth refused to deal with him.

At one point last year, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Beth Jones went so far as to organize a mini-revolt against Bolton, penning a memo to Colin Powell, co-signed by the assistant secretaries from every regional bureau, which complained that Bolton’s campaign for bilateral agreements exempting Americans from prosecution by the ICC had been a failure and should be abandoned. In response to the memo, Powell called a meeting between Bolton and the assistant secretaries. Both sides argued their case, and Powell ended up granting Bolton permission to proceed. In the months since Jones tried to abort Bolton’s campaign, he has signed agreements with 81 countries.

“Bolton’s best kept as far as possible from foreign officials,” says Greg Thielmann, formerly assigned as an intelligence liaison to Bolton (and no fan of his), “but I’ll give the devil his due; he’s been very effective.” Partly, this success derives from the fact that Bolton takes his cues exclusively from the White House. In his book The Case for Bureaucracy, Charles Goodsell writes, “The agency positions in which bureaucrats ‘sit’ have much to do with where they ‘stand.’” Nothing could be less true of Bolton, who follows the “James Baker model” of bureaucratic management—like the former secretary of state, whose ties to Bolton date back 25 years, he views himself as the White House emissary at Foggy Bottom rather than the other way around. “John has had the luxury of Powell delegating red-meat issues and deferring to him on subjects where [Bolton] is closely aligned with the White House, which is quite frequently,” says Gary Schmitt, executive director of the Project for the New American Century. State Department officials often describe Bolton as President Bush’s “alter ego,” but Bush’s actual ego may be closer to the truth, since Bolton comes closer than anyone at Foggy Bottom to being an authentic expression of White House statecraft. As one mystified career State Department employee puts it, “At first we thought that Powell and Armitage would control Bolton. We kept waiting, and now Bolton seems to be controlling them.”

Equally important, while his neoconservative counterparts struggle to transform an ambitious vision into reality, Bolton, when not tearing down in the name of America First, wages a narrowly focused, pragmatic campaign to dot i’s and cross t’s. “John has a very deep anchor, but let’s just say he also has a very long line,” says one of Bolton’s colleagues, by way of explaining how Bolton’s realism extends to operating within the very institutions—and often on behalf of official policies—that he plainly despises. Hence, Bolton, who once said that, if U.N. headquarters in New York “lost ten stories, it wouldn’t make a bit of difference,” has spent the past three years working its corridors—to indisputable effect. Hence, too, Bolton the ideologue invokes Edmund Burke’s admonition that the way to discover “what is false theory is by comparing it to practice,” and, according to Keith Payne, until recently a deputy assistant secretary of defense in the Bush Pentagon, “He sees the world as it is, without any illusions.” This is particularly true of Bolton’s approach to nonproliferation issues, which he approaches in decidedly technocratic fashion. “It’s easy to operate in a dream world,” he tells me, “but the goal is to have an impact and a deterrent effect.”

The contrast here is less one of ends than means. When it comes to North Korea, for instance, Pentagon officials have floated solutions ranging from the hopeful (Kim Jong II’s regime collapsing under its own totalitarian weight) and the far-fetched (encouraging a military coup) to the apocalyptic (plans for a military strike against the North). Bolton, by contrast, has focused his energies on a less ambitious project that responds to the world simply as it is. That project, the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), aims to interdict weapons-related cargo bound to and from rogue states. PSI, in which Bolton has enlisted 15 nations, has resulted in the boarding of several North Korean vessels over the past year. But it netted its biggest haul in October, a shipload of uranium-enrichment centrifuge parts destined for Libya. “The PSI seizure of uranium centrifuge equipment was a major factor in Libya’s decision to give up on WMD [weapons of mass destruction],” Bolton claims. At the time, American and British diplomats had been negotiating with Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi about his WMD programs for months, “but the [Libyans] only came clean after they got caught,” says one intelligence official. Even Bolton skeptics credit the feat. “By staking out a more muscular approach to proliferation threats and raising doubts about the effectiveness of more traditional approaches,” says Robert Einhorn, assistant secretary of state for nonproliferation during the Clinton administration, “the Bush administration has, in effect, challenged the Europeans to show that their preferred methods can work.” Indeed, while Bolton claims not to “do carrots,” in both the Libyan and North Korean cases his “muscular approach,” far from prompting a hardening of their positions, helped achieve the opposite result: Pyongyang’s agreement to the long-held U.S. demand that it negotiate with America and her allies across the same table and Tripoli’s decision to abandon its WMD programs.

In his diplomatic efforts at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Bolton the realist also emerges clearly. Here, too, Pentagon officials have calculated that the surest way to put an end to Teheran’s WMD arsenal is to put an end to the regime that presides over it, by rearming Iraq-based Iranian opposition groups or pinning their hopes on the possibility that, as neoconservative writer Michael Ledeen puts it, “the United States could provide the decisive support that would guarantee success of [a] democratic revolution.” Yet a democratization policy, however politically and morally necessary, is not a counterproliferation policy—not least because Iran’s democrats profess to be as eager to acquire nuclear weapons as its theocrats.

Bolton, by contrast, simply focuses on the weapons themselves. Last September, he fiercely lobbied the IAEA board on Iran’s nuclear program, which responded by giving Teheran until October 31, 2003, to explain itself. Sensing trouble ahead, Britain, France, and Germany then persuaded Iran to sign an additional protocol, allowing for surprise inspections. Challenged by Bolton to take a firmer stand, the IAEA board followed up in November with a resolution that threatened to declare Teheran in violation of the nonproliferation treaty “should any further serious Iranian failures come to light.” Last month, one clearly did, when IAEA inspectors stumbled across designs for a sophisticated centrifuge. To provide an adequate response to the threat, however, Bolton clearly trusts neither IAEA chief Mohamed ElBaradei nor the United Nations as a whole. Hence, even while he presses the IAEA to act, he has pressured Russia not to supply fuel to Iran’s reactors. “There’s absolutely no question that Bolton’s strategy of pressuring the IAEA led its members to finally get serious about Iran’s weapons programs,” says Ray Takeyh, an Iran specialist at National Defense University.

There is, to be sure, something missing here. Despite its thoroughly American pedigree, Bolton’s worldview lacks any trace of the American creed—liberalism. Thus, the neoconservative reading of the war in Iraq does not square with Bolton’s. The former argued that America’s duty would be discharged neither when Saddam Hussein was toppled nor even when Iraq subsequently had a decent government, but only when it became a pivot for democratizing the region. Bolton, by contrast, was arguing months before the war that the United States should oust Saddam and, according to one member of his team, “get the hell out immediately.” Bolton’s pessimistic reading of the international scene kept him from buying into the neocons’ fundamentally liberal assumptions about postwar Iraq and, significantly, distanced him from the controversies that flowed from them.

It has also kept him from grasping the broader significance of the enterprise. “John’s far more skeptical than neocons about nation-building and democratization,” says Schmitt. That understates the distinction, for Bolton has explicitly repudiated both ideas. “We’re not trying to build a platonic international order,” Bolton told me. “We’re responding to specific threats with a national-interest approach.”

His triumph, then, amounts to a triumph of realism, of low expectations. It also says something about the limits of idealism—about neoconservatism, some of whose adherents have gone from being, in Irving Kristol’s famous phrase, “liberals mugged by reality” to purists who no longer attempt to fashion a realistic political ideal; and about liberalism, or at least that brand of liberalism that believes U.S. power should be used only in concert with the international community. Finally, Bolton’s success represents a failure of the international community itself, which too often stands aside while the United States chases its selfish and narrowly conceived interests but which cries “imperialism” when it does the reverse.

Hence, we’re left with Bolton himself, holding up one leg of America’s grand strategy, while the rest collapses around him. It’s not enough. But, as Jack Nicholson’s Colonel Jessep—sounding a lot like John Bolton—put it, “We live in a world that has walls,” and “deep down, in places you don’t talk about at parties, you want me on that wall.” If nowhere else, Bolton belongs on the wall.