The afternoon before Russia’s presidential election, 24-year-old Roman Andreyev waited in line to be accredited as an official voting observer. He knew incumbent President Vladimir Putin would likely come away with a landslide victory, but still planned to spend the evening reading up on how to spot electoral violations and testing himself on an app. “If you do nothing yourself,” he said, queuing up at an opposition leader’s headquarters, “then you can’t demand anything.”

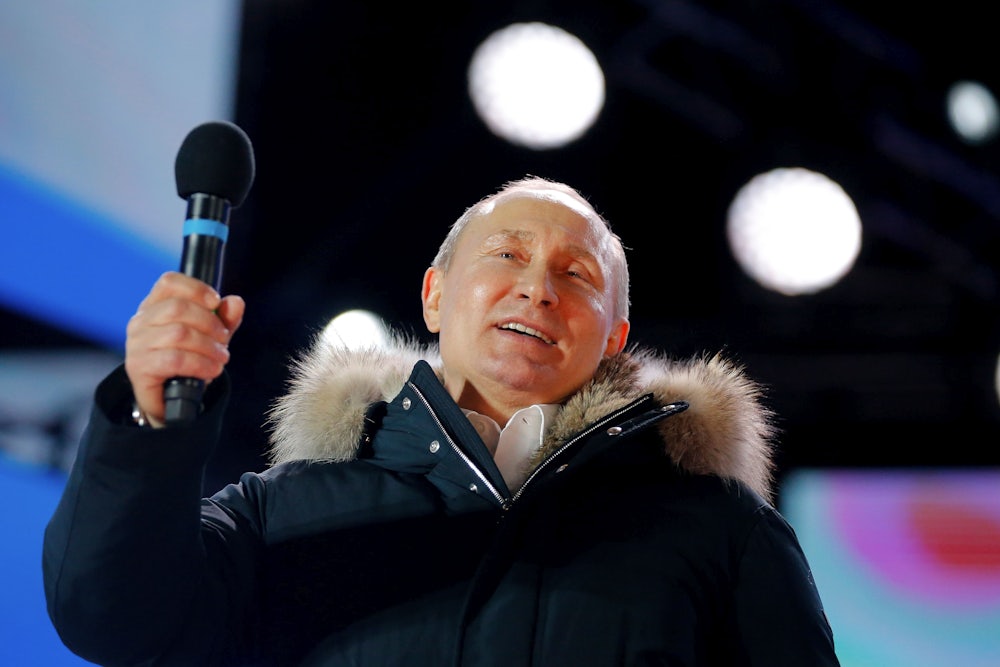

A little over twenty-four hours later, with initial results giving the sitting president over 70 percent of the vote, Putin appeared in front of television cameras and crowds outside the Kremlin walls to thank his supporters. “Russia, Russia, Russia!” he chanted with the crowd.

Andreyev, meanwhile, was coming to the end of his 16-hour shift at polling station 410 in northern Moscow. “Goddamn,” he wrote in a message shortly after midnight. “Everything is bad with Russia.” He returned home in sub-zero temperatures early Monday morning, having signed off on results from the polling station that gave Putin a convincing majority.

The only real uncertainty in 2018 was the margin of victory Putin would achieve. Years of wall-to-wall positive media coverage of his every move and relentless pressure on the opposition means most Russians see no alternative to the status quo. But Kremlin strategists also wanted a high turnout in order to maximize the legitimacy of Putin’s fourth presidential term—a wish fulfilled as final figures put the turnout several percentage points higher than in 2012.

Other candidates, in particular television-presenter-turned-liberal-mouthpiece Ksenia Sobchak and Communist Party candidate Pavel Grudinin, a businessman known for his strawberry farm, provided a veneer of competitiveness. But Putin’s most dangerous opponent, Alexei Navalny—to whose headquarters young Andreyev had gone to be registered—was barred from taking part because of a 2013 embezzlement conviction widely considered to have been politically motivated. Instead, the combative anti-corruption activist called for an election boycott and tried to draw as much attention as possible to electoral fraud.

A cat-and-mouse game between observers trying to spot violations and officials intent on boosting Putin’s numbers has become a routine feature of Russian elections. This time, evidence posted online by observers showed ballot stuffing, pre-filled urns and polling station cameras being deliberately blocked (in one case with a bunch of white balloons). More evidence of irregularities will almost certainly emerge in the coming days, but is unlikely to cast much doubt on Putin’s win, and even less likely to provoke anti-Putin protests similar to those which convulsed Russia after fraud marred parliamentary elections in 2011.

Andreyev was one of the thousands of observers gathered by Navalny’s team and posted at polling stations across the country. Checking voting lists and comparing the number of voting papers issued to the number of votes cast, he saw no irregularities. Surrounded by festivities—polling stations, Soviet style, hosted outdoor games, dancing, clown shows, and historical re-enactments while buffets offered discounted buckwheat, salami sandwiches, caviar and even, in some places, vodka—in the end he resorted to passing the time by helping election officials blow up balloons that read “my daddy voted for the president of Russia.”

Vladislav Yefimenko, 20, another Navalny-led observer, was shocked by how many state employees he saw in his Moscow polling station. “They are zombified and forced to turn out,” he wrote during a daytime message. “These people are blackmailed (firing, retraction of bonuses, etc.) but they see it as something they should be doing.”

Ironically, Andreyev was one of those state employees: as a secondary school teacher, he was pressured by his managers to vote, something he did not initially want to do as a Navalny supporter. He showed messages on his phone from the deputy headmaster at his school asking if he had cast his ballot. When he replied that he had, the deputy sent back a “thumbs up” emoticon. (He didn’t tell the deputy he voted for Grudinin, in what he said was a vain hope the Communist candidate might be able to get enough votes to push Putin’s total under 50 percent and trigger a second round.) Andreyev said he feared his bosses would have found out if he hadn’t voted, and could have arranged for him to be fired.

On Monday morning, with almost all the voting papers counted, the scale of Putin’s victory became clear: official figures showed 56 million Russians voted for Putin giving him 77 percent of the votes cast. This is the highest margin by which any Russian president has won an election since the fall of the Soviet Union. Putin’s closest competitor, Grudinin, got just 12 percent and looks like he will be obliged to shave off his trademark moustache after he bet publicly he would get over 15 percent.

Despite the scale of Putin’s win, tensions are only likely to rise in his new six-year term, at the end of which he is constitutionally ineligible to run again as president. “The succession question is already the main question in Russian politics,” said Ben Noble, a lecturer in Russian politics at University College London, who predicts a rise in elite conflict and new waves of repression. “In light of the uncertainty over Putin’s exit from power—the when and the how—the tendency for opposition to be equated, at the extreme, with treason will only become stronger.”

This opposition is likely to include observers like Andreyev and Yefimenko, who are too young to remember a time when Putin was not in charge of their country. Young people have increasingly come to the forefront in anti-Kremlin rallies organized by Navalny, most notably in March last year when tens of thousands of people across the country took part in the biggest opposition demonstrations in five years. Many of them are politically engaged and get their news from the internet, rather than from the state-owned television stations under the control of the Kremlin.

This enthusiasm for opposition amongst the young has given hope to some that 2018 might be the beginning of the end for Putin. But few of the observers from Navalny’s team could marshal any optimism on Sunday as the totality of Putin’s victory sunk in. “Nothing is changing in Russia,” Andreyev said: Putin will find a way to return for a fourth or even a fifth term. “It’s like Star Wars: Disney have said that while people keep watching, they will keep releasing films.”

Just after 2 a.m. in Moscow, as he finished his election observing shift, Yefimenko sent a message saying that he had been seeing a lot of jokes about Putin’s seemingly endless ability to stay in power, some playing on the fact that last year, Putin reached the dubious milestone of becoming Russia’s longest-serving leader since Josef Stalin, who died in 1953. “It would be funny if it wasn’t so sad,” he wrote.

Both Andreyev and Yefimenko said they would be willing to take part in future protests against Putin, but such popular expressions of anger are only likely to become a real threat to the regime in a situation of economic collapse or if a challenger to Putin from inside the Kremlin sees an opportunity in exploiting grassroots discontent.

Maneuvering for influence among Russia’s elite ahead of Putin’s possible departure will inevitably intensify in the coming years, according to Noble. “This jostling is a constant feature of political life in contemporary Russia, but it will take on an increasingly existential urgency: those who don’t achieve a good position when the music stops in political ‘musical chairs’ will likely fear for the security of their property — and their lives.” For the young dissidents who have grown up in the age of Putin, such pessimism is easy to buy into. Few things have become as predictable as political disappointment.