News spread last week that NME’s print issue is folding, thanks to that old chestnut, the “digital-first strategy.” A number of “Greatest NME Covers Ever” lists germinated across the web in response, celebrating an art form that NME, with its resolute commitment to straightforward photographs of artists and disdain for the norms of graphic design, pushed to new heights. But a good magazine, of course, is more than its cover. It’s a physical relic, a time capsule of culture past. And so it also contains the past selves of those who read it. As an alternative view of NME’s august history as pop’s arbiter, here are seven moments in the life of the magazine and one of its most devoted late-century readers.

1952

New Musical Express is founded. As the minutes count down to the closure of its predecessor, Accordion Times and Musical Express, Maurice Kinn, a music promoter, swoops in and buys it up. No more will Britons buy a paper about the bellows-driven instrument. Instead, a general interest popular music publication is born. On November 14, NME publishes the first U.K. Singles Chart, inspired by America’s Billboard. The chart derives from a poll, conducted by calling 25 record stores on the phone. The first Number One recorded in NME is Al Martino’s syrupy “Here in My Heart.”

1964

In April, the magazine holds the 1963-64 Annual Poll-Winners’ All-Star Concert in London’s Empire Pool. Ten thousand people attend. The Beatles perform “She Loves You” and “Twist and Shout,” among other tunes that you can pretend to hate but have to admit remain bangers to this day. The group receive an award from NME, presented by Roger Moore, who was at that time starring in The Saint. Gerry and the Pacemakers also play, as do The Rolling Stones, The Searchers, and The Hollies.

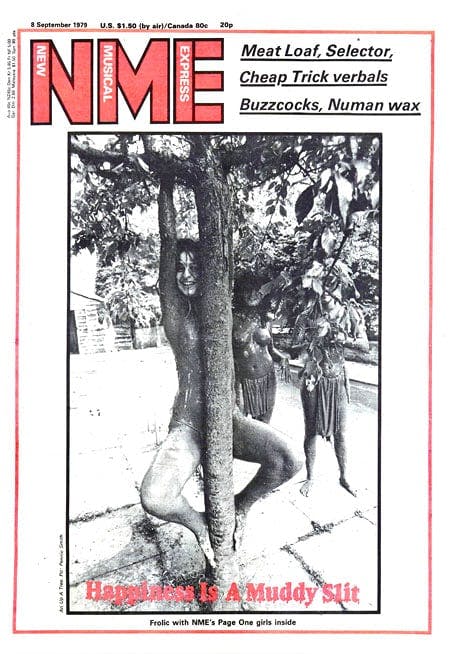

1979

The cover reads “Happiness Is A Muddy Slit: Frolic with NME’s Page One girls inside.” The “Page One” is a joke referring to the Sun newspaper’s “Page Three,” which always features a topless girl. The image is by music photographer Pennie Smith, who also shot The Clash’s London Calling record cover. The Slits are covered in mud and almost naked. The shot seems to be from the same session that gave us the cover image for their album Cut. Former editor Neil Spencer later tells The Guardian that he remembers “having a discussion about these images in the office: Were these crazy pictures of the band stripped off and covered in mud OK or not? Was this titillation, or was it something else?” The controversy is partly about the nudity, and partly about the fact that The Slits “didn’t sell records.”

1986

The July cover is The Jesus and Mary Chain. Mat Snow, who profiles the band inside, gets equal billing. The cover headline is “PLAYING DEVIL’S ADVOCATE: MAT SNOW NAILS THE MARY CHAIN.” This is the year that the BBC bans the single “Some Candy Talking” for making heroin sound too appealing, although singer Jim Reid has claimed it is not about heroin at all. The band had released their seminal album Psychocandy the year before. In a review of November 1985, NME’s Andy Gill calls it “a great citadel of beauty whose wall of noise, once scaled, offers access to endless vistas of melody and emotion.” You can buy the 1986 Mary Chain cover issue on eBay for 10 pounds, British sterling.

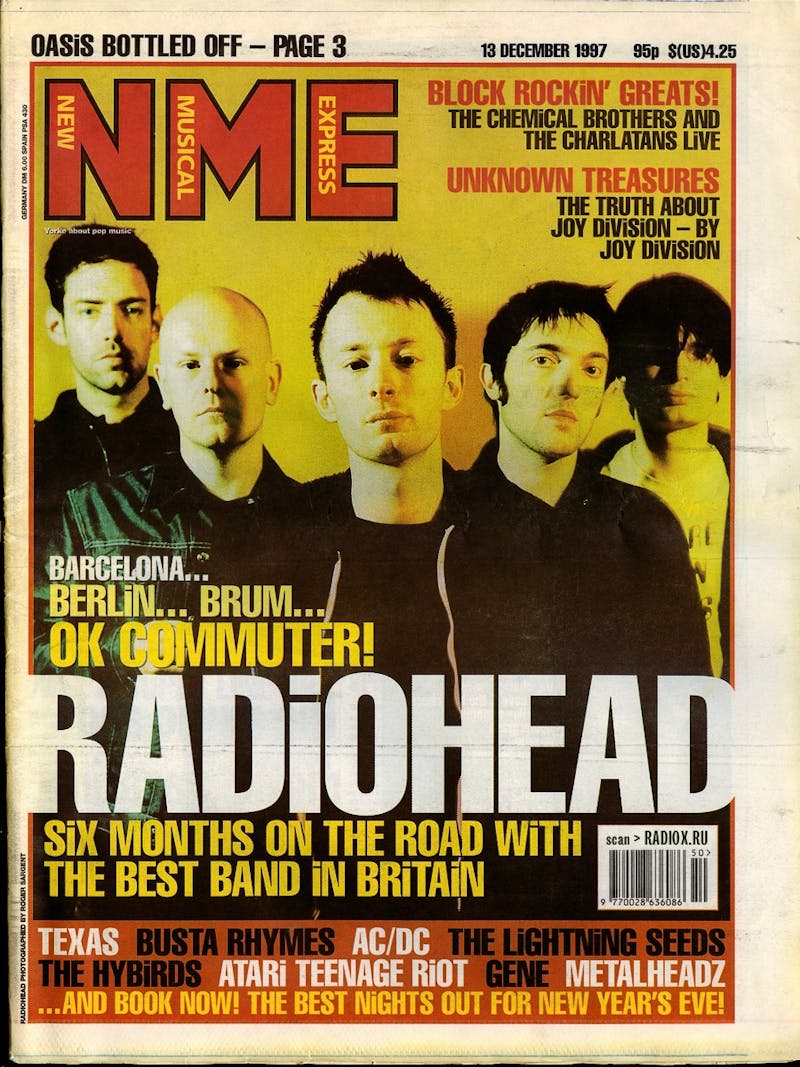

1997

I buy my first copy of NME at ten years old from a newsagent’s in a seaside town in rural England, where my family is on holiday from London. The background is yellow and the members of Radiohead are arrayed in front of it with blank expressions on their faces. I read it from cover to cover in my bedroom. Other bands featured on the cover include The Lightning Seeds, Gene, and Atari Teenage Riot. From reading NME (and Melody Maker and Select and, I’m embarrassed to say, Kerrang!), I develop the mistaken notion that one’s musical allegiances represent the most important thing about a person, and that one can tell how good a person is by the music they listen to. Every Saturday I go to the record store and figure out how best to use their three-classic-albums-for-£20 deal to learn the complete history of rock and roll.

2005

Perhaps in another decade or so, the early- to mid-2000s won’t feel so embarrassing. The R&B of this period has already been redeemed, the stylish minimalism of its music videos (Aaliyah’s “We Need a Resolution,” Destiny’s Child’s “Say My Name”) feeling classic in retrospect. But the British indie mini-boom of this period is hard to look fondly upon. The Kaiser Chiefs are on the cover of NME this year. Inside the magazine we will also find Coldplay and The Stereophonics. White men playing guitar music is at such an incredibly dull pitch that the brief spate of post-punk-inflected groups like Interpol and The Futureheads feels like something new. Or, rather, something old that might be a lifeboat out of the postmodern everythingness that has us all feeling like there’s no longer anything alt under the sun.

2018

It is not possible to recreate completely the first time you turned the page that changed everything. NME opened doors in the minds of many young people, and that door led into culture. My memories of that experience are completely defined by the fact that I was a child, and so my headlong sprint into the new and magical world of guitar music represented something like an entry into the world. Here is a way to be, NME seemed to say, even though that wasn’t quite true. I identified with music to the total exclusion of everything else, to the extent that it ended up separating me from people more than it connected. But that itself is a special memory. The rustling of the low-quality paper of the New Musical Express exists in my mind as a sensory artifact of trying to become a person. It’s going now, and we can’t regret that too much. Music and music journalism have changed, in many ways for the better. The sense memories of today’s kids entering personhood will be different. But they’re forming all over the world, every day, right now. Viva the meaning of music journalism to ten-year-olds; viva NME.