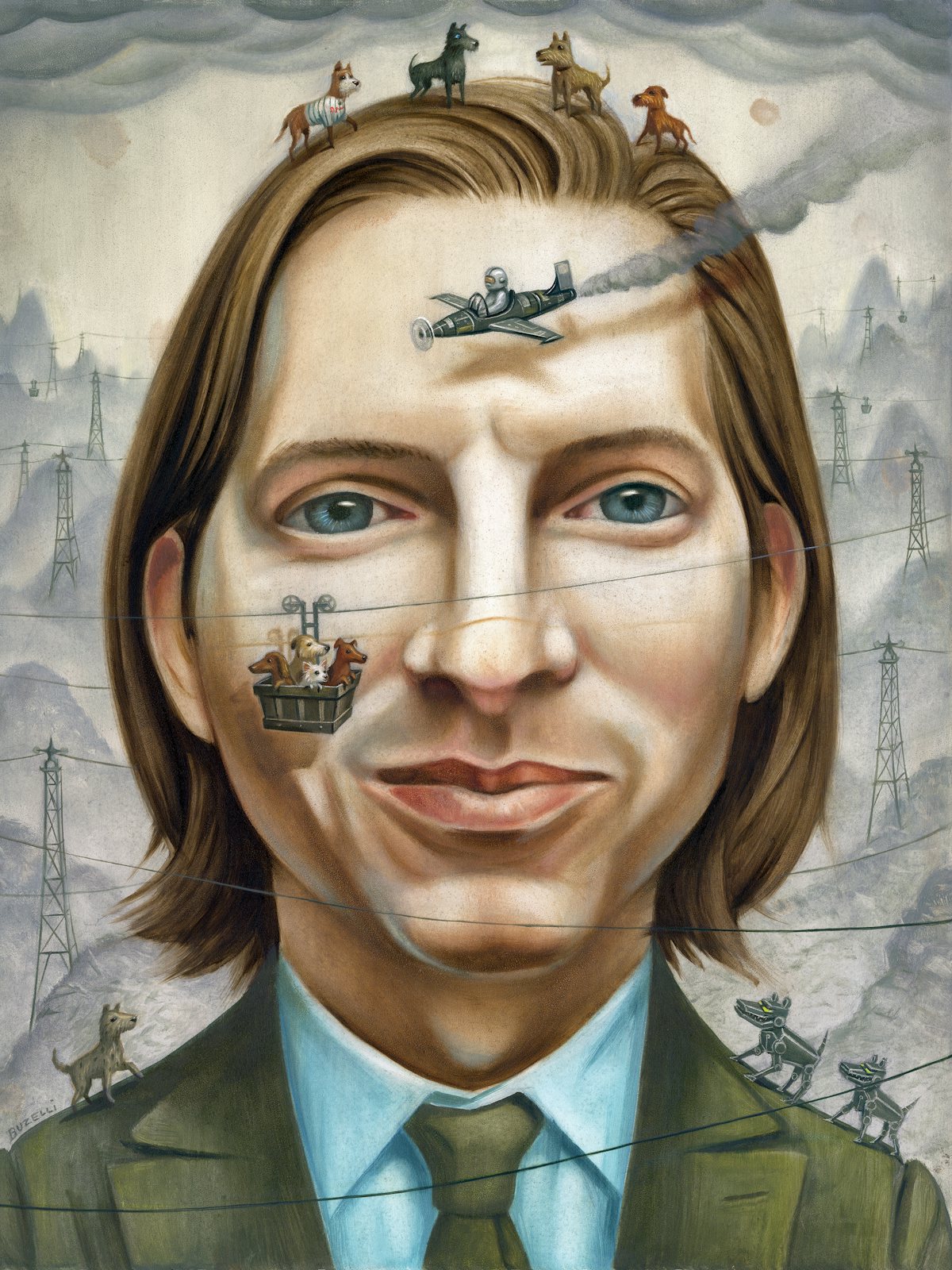

Having been bitten too many times as a child, I don’t love dogs, but I’m not deaf to the pun in the title of Wes Anderson’s new animated film, Isle of Dogs. The play on words (I love dogs, get it?) captures the director’s compound of irony and earnestness, the way he takes puerile things seriously, in a mode of rigorous deadpan. The premise of Isle of Dogs is antically apocalyptic. A city’s entire population of canines—pets and strays both—is the target of a genocidal campaign. The authorities plan first to infect them with man-made illnesses; then to isolate them on an island that previously served as a trash heap, industrial waste site, and clandestine laboratory for nefarious state experiments; and finally to eradicate them, replacing real dogs with a breed of lethal government-issue robot dogs. Isle of Dogs is a children’s movie, but then Anderson’s compass has always pointed to age twelve.

The film’s hero, Atari Kobayashi, is a twelve-year-old boy who loves nothing more than his dog and risks his life to save him. Twelve-year-olds are just discovering the world’s hidden meanings: They’re the perfect audience for puns. For an adult, there’s something like dramatic irony inherent in watching a hero of this age: The idealized twelve-year-old boy sees the world in terms of good and evil. His idealism is uncomplicated. He’s capable of romantic love but hasn’t experienced the messiness of actual sex. His is a masculinity that’s yet to become toxic. His earnestness is adorable and a bit silly. It’s harmless to laugh at him, as harmless as laughing at a pun.

The setting of Atari’s quest is Japan, the fictional city of Megasaki, 20 years in the future. The governing clan has decided to avenge an ancient humiliation under the cover of protecting the city’s humans from the manufactured menace of canine flu. Anderson’s dogs are mangy and emaciated, with bulging, bloodshot eyes, and voiced by Bryan Cranston, Jeff Goldblum, Bill Murray, Edward Norton, and Bob Balaban. (If you close your eyes, it might seem the massacre isn’t being carried out against dogs but against a group of middle-aged American celebrities.) Atari is an orphan, distant nephew and now ward to Mayor Kobayashi, mastermind of the anti-dog plot. Atari has hijacked a plane and crashed on the island in search of his dog, Spots (Liev Schreiber), and the dogs agree to help him, despite the misgivings of their leader, Chief (Cranston), who unlike the others is a stray and feels no loyalty toward humankind. Of course, the boy wins him over: He gives him half a biscuit and a bath.

Atari, of course, shares a name with the console that taught Generation X how to play video games, and as he and his canine comrades make their way east across Trash Island, the frames scroll from left to right as if in a game from the 1980s. Frogger and Space Invaders are as much a point of reference in Isle of Dogs as The Seven Samurai or Star Blazers, the anime series that made its way to American UHF in the late 1970s; for the most part, the future in Isle of Dogs is less digital than the present, with the exception of the government’s drones and drone hounds. Every Anderson film, no matter how exotically conceived, is a love letter to his own analog childhood, and every Anderson film is also a subtle revolt against the digital age.

Anderson was born in 1969 and grew up in Houston, the child of parents who divorced when he was eight years old. Like Etheline Tenenbaum in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), his mother worked on archaeological digs. Like Max Fischer in Rushmore (1998), Anderson was educated in both private and public schools. His early aspiration was to be a writer, but as he told Matt Zoller Seitz in his book of interviews with and essays on the director, The Wes Anderson Collection, he was drawn to film when he started reading books by and about filmmakers as a student at the University of Texas, where he met his frequent collaborator Owen Wilson in a playwriting class. After a success with a short version of Bottle Rocket at the Sundance Film Festival soon afterward, Anderson scored a deal to remake the film as a feature for Columbia under the mentorship of the producer James L. Brooks, the pioneering 1970s sitcom auteur who created The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

Twenty-two years after Bottle Rocket’s release as a feature, Anderson’s work falls into three phases. The early films take place in America and portray juvenile adults and adolescents who behave as if they’re older than they really are. Their themes are arrested development and the curse of the child prodigy. The next phase follows the adventures of Americans abroad—at sea in The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004); on a train in India in The Darjeeling Limited (2007); reconfigured as wild animals in the English countryside in Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009). He returned to America with the summer camp romance Moonrise Kingdom in 2012. Like Isle of Dogs, Anderson’s previous film, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), was an American fantasy of a foreign land. These last two films, which do not focus on Americans—an exchange student named Tracy Walker, voiced by Greta Gerwig, is the only American character in Isle of Dogs—broke out of the touristic mode of the middle phase and set out for closed, imagined worlds altogether untethered from reality.

From the start, Anderson’s characters have been cursed with a delusional nostalgia. It’s easy to look at Bottle Rocket and see just another 1990s comedy about slackers. Until the gang of amateur thieves put on yellow jumpsuits to rob a warehouse, they dress like typical overgrown suburban preppies without fashion sense. But there’s a reason Martin Scorsese cited the film when he told Esquire in 2000 that Anderson was the next Scorsese. Dignan, the twentysomething fuck-up played by Owen Wilson who leads his friends into this folly, fancies himself a gangster out of a ’70s heist flick. It’s a parody Scorsese movie—complete with a classic rock soundtrack, which for two decades would be an Anderson hallmark—about men who never had the chance to become gangsters.

Nostalgic delusion would afflict Max Fischer, who longs to embody the fading traditions of the prep school that expels him. The Tenenbaum children are haunted by the glories of their lost days as child geniuses. Everybody in The Life Aquatic wants to return to a state of being eleven and a half, what Zissou calls “my favorite age.” The Whitman brothers in The Darjeeling Limited fetishize the luggage they inherited from their dead father. Mr. Fox, having gone straight and become a newspaper columnist, wants to return to a life of stealing food from farms. The narrative of The Grand Budapest Hotel is presented through the frame of a memoir by a dead author who, decades earlier at a dilapidated resort, encountered an aging former lobby boy who told him the story of its glory days. It can’t be said that Zero the lobby boy is deluded; he’s filled with sadness because he lost everyone he loved after the arrival of shock troops who look a lot like the Nazis.

Bottle Rocket introduced another recurring character type: the flawed, or malignant, middle-aged mentor, James Caan’s Mr. Henry. As the bad father figure, who double-crosses Dignan, Caan says his lines as if his character from The Godfather, Sonny Corleone, hadn’t been shot up by the Tattaglias but had moved to Dallas to become a landscaper and small-time crook. Rushmore would cast Bill Murray as Herman Blume, who sees something of himself in Max Fischer, because it’s the nature of a midlife crisis to turn a man back into a boy. As Blume, Murray embodied a louche, fiftysomething wreck in need of redemption. The quest of saving the aging man falls to the boy, who surrenders his crush on the schoolteacher, Miss Cross, and instead plays matchmaker between the two adults.

Though Murray has made a second career of it, a cigarette or two dangling from his mouth, it was Gene Hackman who perfected this persona for Anderson as Royal Tenenbaum. He’s a failed parent, a cheating husband, a bankrupted rich man, a casual racist, a liar: a decadent portrait of the charismatic, urbane, and decadent white American male born in the 1930s. He’s redeemed by having his fraud exposed (he’s been faking cancer to get his wife and adult children to let him live with them), being stabbed by his servant, taking a day job as an elevator operator, accepting that a black man will marry his ex-wife and most likely prove to be a more loving husband than he was, and dying of a heart attack.

The redemption of his children, who have to go on living, is a trickier matter. They are a set of three failed prodigies whose early brilliance in business, sport, and theater has been betrayed by their parents’ divorce. We meet them as depressed adults. There’s a grizzly suicide attempt at the film’s climax by the former tennis star, Richie Tenenbaum, when he perceives that his love for his adopted sister, Margot, is doomed. The episode is a preposterous black hole in the middle of the comedy, a grasping at gravitas. Anderson modeled the Tenenbaums on J.D. Salinger’s Glass family—who appeared in a series of his short stories—but the incest plot doesn’t match the war trauma that haunts Salinger’s fiction. The film tips into the maudlin and quickly scoots back to the twee. Similar moves would mar Anderson’s next films—such as the accidental deaths of Zissou’s son in a helicopter crash in The Life Aquatic and of an Indian boy drowned in a river in The Darjeeling Limited.

The Royal Tenenbaums was a commercial success and aligned with the late–Gen X zeitgeist that went by the name hipster. For the rest of the decade, it was impossible to go out in Brooklyn on Halloween without seeing a couple dressed as Margot and Richie Tenenbaum. The thrift-store aesthetic of the costume design, the shabby-chic gestalt, and the theme of dissipated childhood promise connected with the back end of a generation whose achievements did not match its sense of entitlement and so compensated with nostalgia and an aesthetic of reclamation. But Anderson had reached the culmination of his youthful phase. It would be some time before he would again link his eccentricity and cinephilia so neatly to a popular American myth.

Like Isle of Dogs, Anderson’s 2009 adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox was a stop-motion animation feature that built to a finale of military violence between talking animals (with American accents) and humans (with British accents). The daddy issues—Mr. Fox’s son Ash wants to get his father’s attention and a role as his accomplice—are explored within a functional nuclear family, albeit one that’s being hunted. There’s an emotionally superfluous mid-film funeral for a rat, and the classic rock soundtrack tilts away from the Kinks and David Bowie toward the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones. It was proof that there wasn’t much distance between a Wes Anderson movie and a commercially viable children’s movie. Eliminate the swearing and the sexual innuendo, and you’re mostly there.

Perhaps making an actual children’s movie prepared him to conceive the sort of film he wanted to make all along: a movie about childhood romance set in the mid-1960s off the coast of New England and shot in the style of the French New Wave. Moonrise Kingdom is about actual twelve-year-olds who escape from home and from camp and from their torments. These aren’t idealized children but troubled outcasts. When they ask each other what they want to do when they grow up, both of them say they simply want to have adventures. Watching them, you only hope they’ll be spared more disappointments and won’t disappoint each other. Their plight is heartbreaking, their romance is sweet, and within its own boundaries, the film is a masterpiece.

An exchange between Anderson’s best-realized heroine, the moody and punchy Suzy Bishop, and her soon-to-be unofficial husband, the orphan camper Sam Shakusky, is romantic without being unchildlike: “I always wished I was an orphan. Most of my favorite characters are. I think your lives are more special.” “I love you,” he tells her, “but you don’t know what you’re talking about.” The quest of the tweens in love is delicately balanced with the dramas among the adults trying to bring them home and to heel. An interlude on the beach allows for homages to Godard and Truffaut. The lightning-storm finale occasions daring rescues without unnecessarily slaying any characters. It’s spectacular without being emotionally overwrought, and the orphan boy is in the end granted proximity to the girl he loves as well as a new father in the local police chief played by Bruce Willis, in yet another coupling of the troubled boy and the damaged middle-aged man.

Isle of Dogs is, like The Grand Budapest Hotel, an adventure story framed by an episode of historical trauma. In the new film, the crisis is present instead of looming, but it’s also lighter because the potential victims aren’t human. The false-flag public health crisis, the tribal nationalism of the Kobayashis, and government suppression of scientists all suggest parallels with real-world politics, but allegory isn’t the film’s aim. Anderson’s lonely rebels are pitted against government-stirred “anti-dog” hysteria in a Manichean struggle not unlike the conflict in one of his favorite films from childhood: Star Wars. Atari in his tattered flight suit looks more than a little like Luke Skywalker, and his canine companions aren’t far from R2-D2 and C-3PO, who were modeled by George Lucas on characters from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress. The referents have come full circle.

Language has a curious status in Isle of Dogs. The viewer is closer to the dogs than to most of the people in the film. The dogs’ barks have been “rendered” in English, as has Courtney B. Vance’s booming, ominous narration, but all the human characters speak in their native languages, without subtitles. Much of the dialogue is in Japanese, voiced by Japanese actors. It can’t be understood either by the dogs or by any audience members who don’t speak Japanese, though many statements made in public and on television are translated by an interpreter voiced by Frances McDormand. Her lines are reminiscent of World War II–era newsreels, another way the film’s future looks a lot like the past.

Anderson enlisted Japanese collaborators, among them Yoko Ono, who voices a scientist working on the side of the dogs, and Kunichi Nomura, who voices the villainous Mayor Kobayashi and is credited for the story, along with Jason Schwartzman, Roman Coppola, and Anderson (who has sole credit for the script). Yet the film isn’t above simplistic cultural gags, like the use of poison wasabi as a method of assassination. The air of unreality is further deepened by a soundtrack heavy on percussion, shown throughout the film to be played by drummers in a gym with a basketball hoop dressed as if for sumo wrestling. The Japan of the film is less a real place than a staging ground for a set of cinematic references: Kurosawa, anime, etc. As a place, the film’s Japan is thoroughly imagined and thoroughly imaginary, like the anachronistic New York City of The Royal Tenenbaums.

The ironies of that film were easy to read in its costumes and obvious cultural references, with parodies of Oliver Sacks, Cormac McCarthy, and characters from J.D. Salinger. In Isle of Dogs, Anderson is a bit more sly, putting a pun in his title and naming a character after a video game system without winking. Or if he is winking, the winks are so thoroughly wrapped in a story of mass dog rescue that you could be forgiven for not noticing them if you weren’t, as I was, looking for them.

Dogs on movie screens either bite or they’re adorable. Anderson’s dogs are the latter, and there’s something inherently corny about them. There’s also something stunted about Anderson’s eternal regress to age twelve. If blockbuster American cinema, now bleeding into the prestige category, weren’t already so dominated by superhero movies, it might be easier to stomach an art-house auteur bent on concocting ever more sophisticated and exotic ways not to grow up.