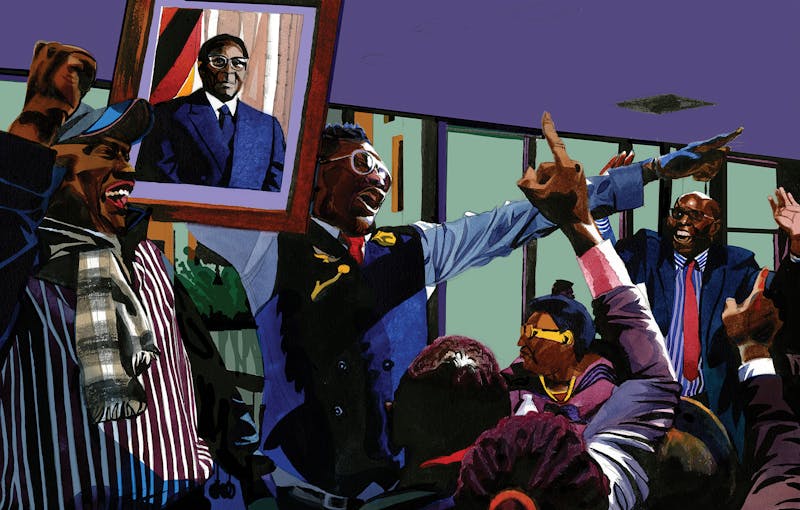

At the headquarters of Zimbabwe’s ruling party, a portrait of the former dictator, Robert Gabriel Mugabe, stared down from a high wall enclosing a bank of elevators. He wore a gray suit, a white-dotted navy tie, and a matching pocket square. His etched jowls were imposing. He looked much younger than 93.

I took a moment to gape. So far, on my trip to Harare, three weeks after a coup deposed Mugabe in November 2017, I had seen no pictures of the man. Once mandated in state buildings, they had been taken down swiftly after the coup. A teacher I met described the scene in her school on the day of his resignation. “One teacher came to the staff room and said, ‘Auctioning, auctioning, anybody want a picture of Mugabe?’ and someone put up his hand and said, ‘Fifty cents, I’ll give you 50 cents!’ and then he said, ‘OK, I’ve got 50 cents, anyone else?’ and someone else said, ‘Ten cents’ and he said, ‘Sold to the guy with 10 cents!’ ” For a while there were blank spaces—empty rectangles where once there were portraits—throughout the capital. Then, on the third day of my visit, a picture of the new president, Emmerson “E.D.” Mnangagwa, went up behind the reception desk at my hotel, above the aquarium full of flat, orange fish.

In the party headquarters, I went up and down in the crammed elevator with its sweating, besuited apparatchiks. It was only when I came back to the foyer that I saw why Mugabe’s picture was still there: It had been painted, not pasted, onto the tiled wall. It would take a while before someone could get up there on a ladder and scrape it off.

Zimbabwe under Mugabe had become a bleak place—a country with lines for food and money, more than 80 percent unemployment, and a constant fear of being hounded by the police and secret agents from the Central Intelligence Organization or CIO. Zimbabweans were now being given a break from this torment. The scores of police roadblocks that had littered the streets of Harare were gone; the car-stopping spikes lay piled on traffic islands like the teeth of an enormous fish. You could now drive through the city without fear of being flagged down and stripped of cash over some spontaneously invented offense like failing to travel with a fire extinguisher. You no longer had to consult a WhatsApp group to learn which streets to avoid, or pack a paperback in case you were stranded by the side of the road for refusing to grant a cop his baksheesh. You could just drive.

Something similar was true of conversations. Under Mugabe, opponents of the regime were arrested, beaten up, and disappeared. People had grown wary and suspicious of each other. Few condemned Mugabe publicly. Now the CIO, Mugabe’s ears, had been plugged up. The agents sat in bars and cafés twiddling their thumbs over smartphones. And Zimbabweans, who had grown resentful of the father of their nation, talked about the horrors of those years. “Some friends have died from stress,” Winnie Wakatama, a 75-year-old retired insurance sales representative, told me. “A person who would have been able to drive a car, you come to the point of not being able to even afford the car; you have to sell it to survive for a few days.” Her husband, Pius, a newspaper columnist and anti-Mugabe activist who had been jailed several times, said, “When I heard that Mugabe was really gone I couldn’t believe it until every channel was showing it, and I said to myself, ‘It’s true.’ ” Zimbabweans who had fled the country—nearly a quarter of the 16 million population—spoke of returning.

It was easy to forget, amid all this relief, that the new president had come to power not through an election, but because the military had seized power.

I had planned a trip to Harare long before the coup. I was to cover the doddering dictator’s reelection campaign and his attempt to elevate his 52-year-old wife, the infamous “Gucci” Grace Mugabe (so nicknamed for her shopping sprees), to the vice presidency. To assist me on the ground, I had hired a local journalist, Columbus Mavhunga. Columbus, age 40, was prompt, direct, helpful, funny, and hardworking. He responded almost instantly to queries and had a freewheeling, can-do attitude. Like most Zimbabweans, he saw an opportunity in a foreigner coming to visit. Because Zimbabwe discontinued its currency in 2009, following a disastrous cycle of hyperinflation, Zimbabweans can’t use credit cards to make purchases abroad. Columbus asked me to bring him a few items of golf clothing from Loudmouth Golf—the pink shorts and flame pants revealing a flamboyant personality. Back in the United States, the frictionless mecca of capitalism, I happily complied.

Then, on November 14, shortly before my planned visit, tanks appeared on the streets of Harare. I sent Columbus a message on WhatsApp asking him what the hell was going on. “Not now man,” came the reply. This was uncharacteristic; the vexed tone wasn’t right. Then, checking Columbus’s Twitter, I saw the following message: “My phone was seized last night.... Eishhh. (Nt taking questions on this sensitive matter.) In pain emotionally n physically”

I was worried for Columbus but also, to a degree, for myself: I was going to Harare on the pretext of writing a novel, and Columbus’s phone contained much of our private correspondence. I sent him an email. The reply that came back was the kind of response only a dictatorship can generate:

Press card gone, iPhone and $157! I am now resting after being discharged from a private clinic where a doctor confirmed that but a colleague had a fracture on his hand. I am still in pain physically and emotionally. I can’t work for days. Sitting n walking a problem. I am typing with one finger. One nail gone—damaged during the torture. Sitting and walking are major problem. Bruises all over the body.

Tense in Harare man.

On the night tanks had appeared in the city, Columbus heard that the military would be holding a press conference at ZBC, the state broadcaster. When he rushed over there, however, he and two other journalists were directed to army headquarters, in the center of Harare. They arrived at 11 p.m. That was when Columbus’s nightmare began.

The journalists didn’t know it, but at that moment, the army was seizing ZBC and encircling Mugabe’s compound; the dozen soldiers outside army headquarters would have been particularly jumpy.

“Why have you come?” one soldier asked, flagging the car down.

Nights in Harare are dark. The streetlights don’t work, even in the governmental center of the city. This creates the impression of being in a kind of genteel forest. The only illumination was from the journalists’ headlights.

When the journalists said they were there for a press conference, the soldiers asked for IDs and searched the car. This was standard; the men complied. Then the soldier who was searching suddenly stopped. “How do you know about the press conference?” he asked. “This is only for ZBC. Either you are CIO officials or you work with them.”

Before they could respond, the three journalists were herded across the street and made to lie on their stomachs on a grassy verge. Then the beatings began.

They were hit on the back and buttocks with batons and gun barrels. They couldn’t move, and when Columbus tried to defend his butt with his hand, the soldiers smashed it, too, tearing off a part of his right thumbnail and opening a gash in the skin.

His ankle was also hit. After a while, numb with pain, Columbus stopped screaming. “This one is rude, why is he not responding to these beatings?” a soldier asked. Another soldier walked on him. Columbus could barely feel it through the sedimentary layers of pain.

The journalists screamed out various pleas—they were just doing their work, they were here for a press conference, Columbus even claimed he was related to a soldier—but these failed.

“Let’s shoot them,” a voice said.

“No, let’s not.”

“OK, Shef,” the soldier responded. (“Shef” is a slang form of “chief.”)

Finally, exhausted from hitting the men and probably realizing they weren’t spies after all, the soldiers told them to go home. The other two journalists got into the front of the car, but Columbus couldn’t lift himself up. Three soldiers gathered him and threw him into the backseat. Then, as the car rolled away, a soldier smashed the windscreen and passenger window with a baton. The car braked. From years of being trained in the dangerously whimsical ways of a dictatorship, the journalists knew you had to stay put at the scene of an accident if you wanted the police and insurance to process it. That training had kicked in instinctively, even after 20 minutes of beatings.

“Go!” the soldiers screamed, and the journalists drove off.

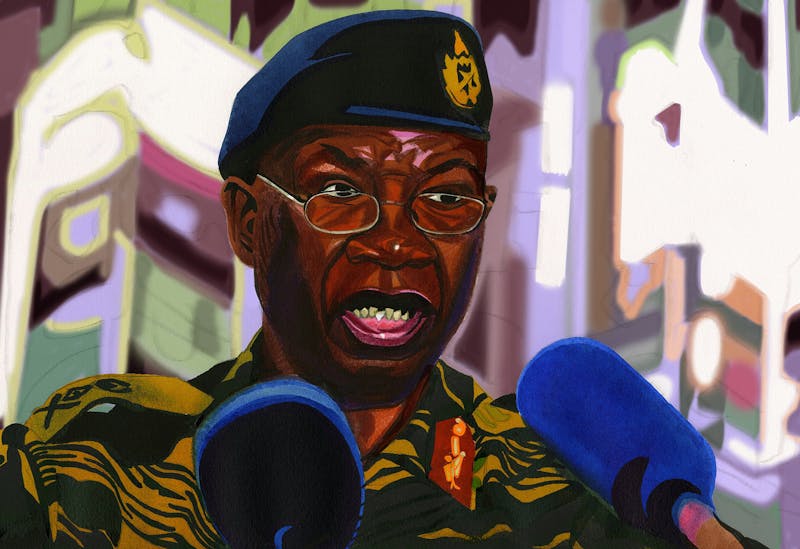

Columbus was still in the hospital when, at 1 a.m., a general named Sibusiso Moyo came on television. Sitting in the ZBC studios, dressed in fatigues, and reading from an iPad, he informed Zimbabweans that something called “Operation Restore Legacy” had begun: the beginning of the end of Mugabe’s 37-year rule.

Three weeks later, as Columbus drove me from the airport through a cityscape of broad colonial roads, reddish ferrous soil, weedy lots, agaves, and towering bougainvillea, he seemed optimistic. “Immediately from the hospital, I felt that I want to leave the country,” Columbus said. “And then I said—to where? Zimbabwe might be entering a new era, and I want to be part of a new era, and I’m hoping it’s an era where journalism is not a crime.”

It was breezy and warm—the hottest part of the day had passed. Harare felt empty. By the side of the road, a woman bent down over bony branches of firewood. Vendors displayed fruit on bamboo scaffoldings. There were no roadblocks or policemen in sight.

My fears about Columbus’s confiscated phone had been unfounded: He had remotely deleted its contents, and besides, the new regime had let me in without fuss. Still, at the airport, after coming off the plane, like all other passengers, I had been made to stand on a rectangle of red carpet and face a camera. I found this surveillance creepy. Later, I learned it was an Ebola test. My mind was inventing symptoms of a dictatorship even where there were none.

I asked Columbus what he thought of the fact that Mugabe had been allowed to keep his house, his security detail, and his travel allowance—rather than being executed like his old pal Qaddafi. “He’s not free like me—or free with certain restrictions, like me,” Columbus said. “Mugabe won’t last an hour on the street—people will murder him.”

Columbus is a sturdy, self-possessed man with a scar under his right eye and a habit of raising his eyebrows and shaking his muscular, shaved head when he makes a point. He wore white shorts and a striped long-sleeve T-shirt—the uniform of the tropics. He told me he was worried about permanent damage to his left hand. “My daughter keeps saying, ‘When are you going to play golf?’ ” he said. “Because I bring goodies after golf, and I say: ‘I’ll go, I’ll go.’” He was in too much pain to lift a club. Typing was a problem, too. It was only recently that he was able to turn the ignition on the car and put it into gear without assistance. And I could see a red gash on his right thumb and the disfigured nail; I kept looking at it as he clutched the steering wheel of his silver Mercedes and blasted Jah Prayzah, the military-themed musician whose song, “Kutonga Kwaro” (“How the Hero Governs”), had become the anthem of the coup.

That first night, Columbus took me to his golf club—he was still going there to drink—and I got a sense of the city in transition. Middle-aged men were slouching and joking, tired from golf, over tumblers of whiskey at long, raised wooden tables. When a woman—the only one there—walked in, a mustachioed man roared, “I’m young, free, and single—I just want to mingle!” The woman laughed it off. It seemed very anglophone, the way clubs in India, where I grew up, do. And of course, this being Zimbabwe—a former British colony whose dictator had been obsessed with education—everyone spoke fluent English.

But the relaxed atmosphere of the bar, with its lavish balcony and view of a dark, tropical golf course and the waving tops of palm trees, concealed another reality. In the last year, the club had been infiltrated by CIO agents posing as members. Three agents, Columbus whispered to me, were sitting on a sofa to one side watching soccer on a mounted television.

“Now they’re just playing golf—more so now that the CIO has been dismantled by the government,” he said. Nevertheless, Columbus warned me that if any one of the men came up to us, he would introduce him as “my good friend” so I would be clued in.

This happened a few minutes later when an unassuming man named Eddie walked by our table.

“Eddie!” Columbus said, hailing him down. “Eddie, he’s a banker, but he doesn’t give me any loans. He’s a very good friend of mine. This is my friend from India. You know, this Eddie, for all his sins, he’s not a good guy. Eddie, where’s my loan? Aren’t you my banker?”

“There used to be risk in the country, now it’s gone down,” Eddie said. He smiled awkwardly, baring his evenly spaced teeth. Then he walked away.

It was hard to detect any menace in him. A little later, getting drunker, Columbus turned to me and whispered, “I have a friend in the CIO.” I told Columbus I’d like to meet this friend in the CIO.

“Why would you say I have a friend in the CIO?” he said. Then he whispered. “You should just say ‘your friend, Columbus.’ ” It was hard for me to tell what was bravado, what was performance for a foreigner, and what was true. Columbus was about four whiskeys deep at this point. When I wrote in my notebook, “3 guys from CIO watching soccer,” Columbus bent over the page, drew a dark circle over the word CIO, and blotted it out.

It seemed then that Columbus was flashing between the old caution and the new freedom—often instantaneously. And this behavior, no doubt, was further heightened by the strange episode in which he had been beaten because the soldiers thought he was with the CIO.

Modern Zimbabwe wasn’t supposed to be a police state. In fact, when Mugabe came to power in 1980, following a 15-year liberation struggle against Rhodesia’s white supremacist rule, he was seen as an antidote to the colonialists’ repressive policies.

He was also recognized worldwide as an extraordinary figure. A former teacher, a revolutionary radicalized in South Africa and Ghana, a thinker who had acquired three additional degrees during his decade in a Rhodesian prison, he was brilliant, eloquent, and taciturn. Father Brian MacGarry, an Irish Jesuit priest who works in the poorest parts of Harare, recalled encountering him at a meeting of revolutionary leaders in 1975, before independence. While the other leaders were cagey, MacGarry told me, Mugabe got up and said, “I’ve just done ten years in jail for saying what I think, and I’m going to say what I think now, and I don’t care what they do about it.” “That was precisely what people were looking for at that time,” MacGarry said.

Better still, despite the horrors visited on him by the Rhodesian regime, the 57-year-old Mugabe was conciliatory toward the country’s white population. The 1979 peace agreement brokered by the British, who ruled the country until 1965, when a white Rhodesian government declared independence, asked that any future black-majority government not undertake land reform—the redistribution of white-owned lands to dispossessed blacks—for ten years. Mugabe, who came to power in 1980, honored the agreement. He appointed the white Rhodesian CIO chief as his intelligence chief and asked the commander of the armed forces, also white, to stay on. He was humble; he knew he was a revolutionary with little experience in government. In 1980, he was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

But power magnified the flaws in his personality. Never a fan of dissension, he ordered the suppression of rebels in the region of Matabeleland—peopled by the Ndebele, the second largest tribe in the country after his own, the Shona—resulting in some 20,000 deaths, mostly of civilians. When the Zimbabwe Catholic Bishops’ Conference condemned the violence, he responded with what would become a trademark grandiloquent acidity: The bishops were, he said, “mere megaphonic agents of their external manipulative masters.” Apartheid-era South Africa’s meddling in Zimbabwe’s internal affairs, meanwhile, stoked his paranoia about all whites. For many liberal observers, Mugabe had unforgivably crossed over into tyranny. But the majority still worshipped him as a liberation hero and the father of the nation—a man who had taken the country from 45 percent literacy to 80 percent in a mere ten years.

By the late 1990s, though, this enthusiasm had waned. A number of factors—a costly involvement in the Second Congo War, the ballooning Asian Tiger crisis, corruption, and years of drought—came together to enlarge the deficit. Food riots erupted. Soon, to appease his base of war veterans, Mugabe undertook the delayed land reform and turned himself into an international pariah.

Land reform had always been a pillar of Zimbabwean independence, and no one can fault it on principle: Zimbabwe was a highly unequal country, with 6,000 white farmers hoarding the country’s most fertile land. But Mugabe not only allowed violent takeovers of commercial white farms but also distributed them to cronies who had no training in agriculture. The agricultural sector collapsed, taking the entire economy with it. The West piled on with sanctions. To service debts, Mugabe began printing money mindlessly, inaugurating an era of hyperinflation not witnessed since postwar Hungary. Inflation peaked in 2008 at a year-over-year rate of 89 sextillion (that’s 89 with 21 zeros) percent, with one U.S. dollar equaling anything from 71 billion to 2.5 quadrillion Zimbabwean dollars. Cashiers weighed money instead of counting it; prices in shops could fluctuate while you browsed. Accountants issued memos advising employees on how to deal with currency amounts with 120 zeros. Barbecues sprang up in lines outside gas stations—that is, when people had food. But in 2008, when Zimbabweans tried to vote Mugabe out of power, he responded with extreme violence, sanctioning the killing of opposition members and forcing the popular opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, into a power-sharing agreement only to sideline him. (Tsvangirai died in South Africa this February.) At 85, Mugabe had become an absolute dictator—a man who played up his anti-colonial rhetoric to distract from his misdeeds. “Shame, shame, shame to the United States of America. Shame, shame, shame to Britain and its allies,” he intoned in a U.N. speech in 2013, blaming the West’s “filthy sanctions” for his country’s woes.

He also built a $10 million mansion for himself in the tony Harare suburb of Borrowdale and acquired a much younger wife, Grace. He was 63 in 1987 when they met; she was 22 and one of his secretaries. (His first wife, Sally, was dying of kidney failure at the time.) From the beginning, Grace was considered an upstart and a usurper without liberation credentials. She lied flagrantly about her husband’s wealth (“My husband is literally a civil servant,” she told an interviewer. “He earns very little”), embarked on international shopping sprees, and punched a British photographer who tried to snap her in Hong Kong. (Her diamond-encrusted rings cut his skin.) She became even more unpopular when she entered politics in 2014. To Zimbabweans, she represented an endless extension of a regime they despised. Much of the country was against her, but others in Mugabe’s party, ZANU-PF, saw an opportunity and aligned with her. This gave birth to the so-called Generation 40 or G40 Faction. The other faction, led by Vice President Mnangagwa, known as “The Crocodile,” was called “Team Lacoste.” The question became: Who would succeed a 93-year-old man?

In August 2017, Mnangagwa fell sick after eating ice cream at a rally; he was rushed to a hospital with severe vomiting and diarrhea. His supporters accused Grace of poisoning his ice cream. Grace responded with something like delight. “How can I kill Mnangagwa?” she asked. “I am a wife of the president. Who is Mnangagwa on this earth? Who is he? I want to ask, what do I get from him? Killing someone who was given a job by my husband? That is nonsensical.”

Then, in early November, the factional fight boiled over. At a G40 rally in Bulawayo, Grace was lashing out at the Lacoste faction when the crowd began shouting “You know nothing” and “You are too junior.” Incensed, Robert Mugabe rose to her defense—as much as he could at his age—and immediately blamed his right-hand man of 40 years. “I am told that this is being done in the name of Mnangagwa,” he said. “Did I make a mistake in appointing him as VP?” The next day, he fired Mnangagwa and stripped him of his security detail. Mnangagwa feared for his life and fled to Mozambique and then South Africa. From there, he flew to China, where he met General Constantino Chiwenga, the commander of the Zimbabwe Defense Forces. Together, they decided they would topple Mugabe. (It is believed that China, a large investor in Zimbabwe, tacitly approved the coup without being directly involved.)

Mugabe, meanwhile, got wind of Chiwenga’s perfidy and ordered the police to arrest him when he landed in Harare, on November 10. Chiwenga was better informed. He had soldiers dress up as baggage handlers and infiltrate the airport. When they took off their baggage uniforms to reveal their fatigues and automatic weapons, the gathered policemen simply fled.

With the police disarmed, the army tried to negotiate with Mugabe. He wouldn’t back down. On November 14, the army surrounded Mugabe’s mansion. Other members of G40 were arrested. Soon afterward, at 1 a.m., General Moyo appeared on the state broadcaster to issue his statement about Mugabe’s safety and how only the “criminals around him” were being arrested. Using WhatsApp and social media, the army’s supporters urged people to come out on Saturday, November 18, to protest Mugabe; they guaranteed the citizens’ protection. The people didn’t have to be asked twice: Zimbabweans of every race, class, and tribe poured into the streets. “I was shocked,” Norman, a taxi driver who took me to a night market, told me. “I don’t know where the white people came from. The town was full of white people.” The citizens marched, sang, and danced. Many were wrapped in bright Zimbabwean flags. Citizens high-fived soldiers and took selfies in front of tanks.

Under pressure, Mugabe came on television on November 19, flanked by generals, only to stonewall, saying that he acknowledged the “concerns” of the army but would stay on as president for the party convention. Frustrated, Parliament began a process to impeach Mugabe. Behind the scenes, furious negotiations were unfolding. Father Fidelis Mukonori, Mugabe’s spiritual adviser and an old regime-sympathizing priest, was mediating. On November 21, Mugabe finally sent a letter to Parliament, stating that he was resigning “with immediate effect” for “the welfare of the people of Zimbabwe and the need for a peaceful transfer of power.”

The letter was read by the speaker of the Parliament amid singing and dancing. A seismic roar of relief and jubilation rang through the capital.

A day later, Mnangagwa flew back from South Africa and was sworn in as interim president at the National Sports Stadium. A crowd of 60,000 Zimbabweans cheered from the bleachers. When the police chief walked onto the field, he was booed.

Ed Whitfield was one of the people celebrating. On the day of the protests, he, his wife, and their two youngest children had driven into the center of town; one of the kids had been wrapped in a flag and held aloft by two soldiers. (His wife, Katherine, was the teacher who had told me about the impromptu auction at her school.) The family’s hatred of Mugabe was personal. In 2001, Mugabe’s followers had seized Ed’s 2,500-acre farm; he and Katherine left the country only to return two years later. Ed now worked as a building contractor and lived in Borrowdale, not far from Mugabe and General Chiwenga.

Before Columbus and I drove over to Ed’s house on Sunday morning, he emailed me directions: “Keep going up to the top past General Chiwenga (tank parked on right). About 300m on the left is us. See u then!” And indeed, as we drove to the house, we passed a long, camouflage-painted armored vehicle with a gun turret. Two young soldiers in mustard-colored berets and high black boots guarded the vehicle. Behind them, Chiwenga’s house was a gray, blocky modernist structure busy with many banks of windows and “C&M” (for Constantino, his first name, and Mary—his wife’s) emblazoned in gigantic cursive on the side.

Ed is a pleasant, barrel-shaped white man of 46 with a sunburned face and alarmingly red, scratched-looking skin under the fur on his arms. He met us at the gate of his ranch-style house with shouts of “Karan!” “Columbus!” A former college rugby player, he wore khaki shorts and a striped blue polo shirt with his collar popped in a preppy-dad style, a sprig of white chest hair showing.

First, he took us to the top of the hill to show us the view of Mugabe’s house, where the former president was being held under house arrest. Two stories of blue, curved, Chinese pagoda–like roofs rose out of a valley between low, verdant hills blanketed by msasa trees. At the end of a sparkling mowed lawn sat a gazebo—also with a blue roof. You could imagine rich people taking a dainty high tea there. On the day of the coup, it had been possible to peer down and see soldiers arresting the Presidential Guard and ferrying them away in trucks. Afterwards, “Chiwenga actually came up to one of my neighbors and apologized to him about the soldiers” in the area, Ed told me. “He said, ‘I’m just checking on the Blue house, seeing what’s going on there. Sorry for the invasion.’ ” I suddenly had the feeling that the coup was a much smaller event than advertised: a power struggle between two rich neighbors.

Ed led us inside, and we sat on his veranda with him and Katherine while their blond six-year-old twins (two of five boys) ran in and out. Katherine, who is English and was outfitted in an athletic jacket and capri pants, was irrepressible with stories about the day—the excitement of finally being able to demonstrate. But then, talking about the protests, Ed suddenly broke down in tears. “I thought of the farm and the 400 people that worked for me and their families—and all because of this guy. Everyone just felt this solidarity, for their pains.”

Ed had led a good life in Zimbabwe before land reform. He ran a successful farm that produced paprika, tobacco, chilies, passion fruit, and maize. Then, one day, men from Mugabe’s ZANU-PF appeared and began building a kraal—a round wattle and daub hut with a pointy roof—right in front of his farmhouse. They threatened, humiliated, and beat up his workers till they left. They set fire to trees, put cattle in his seedbeds, and kept posting misspelled signs saying PECK AND GO. Ed was taken to a police station and forced to cower in a corner and say, “I’m a white colonial, I’m sorry, I’m leaving,” as policemen spat on him. After a year of this, Ed and his wife sold their equipment at a loss and emigrated to England. But, having been born and brought up in Zimbabwe, he missed his home. Two years later, they returned to Harare. He started a food export business and then a construction company, and he had clearly done well: In addition to the house, he owned a small airplane and several cars, and employed a few servants. He seemed traumatized by what Mugabe had done to him, but he also conceded that there was some good that came from land reform. The previous generation, including men like his father, had been white supremacists who felt little compunction about the fact that their wealth came from dispossessing blacks. “It destroyed an arrogance in white society,” Ed said. “It put us all on a level playing field, and it united us all against one common enemy [Mugabe].”

Every person in Zimbabwe, rich or poor, has a story of being undone by Mugabe. By 2007, inflation had wiped out everyone’s savings; people of all classes returned to zero, with a lucky few subsidized by relatives who had already fled abroad. It was a cultural revolution without a cultural project. Then, in 2009, the economy was “dollarized,” a recognition of the reality that most trade was happening in U.S. dollars anyway. Now all transactions occurred in dollars—ratty and brown from overuse—or in so-called Zimbabwean “bond notes,” which were supposed to be 1:1 with the dollar but were more like 1:1.3 because no one trusted the government backing the bonds.

It was strange to be in a country where the government had hated the United States but hungered after its currency. Columbus, for example, always paid for my expenses with his card and asked me to give him cash. A similar thing had happened over the years with cashiers in supermarkets and stores. As customers lined up, a relative of the cashier standing by would swipe his or her card on the customer’s behalf and pocket the cash. Supervisors got wind of this and started patrolling the cashiers. The supermarkets desperately needed dollars, too: It was how they paid for imports.

The cash shortage affected people in much more serious ways: Many were starving. Across from my hotel downtown, I had seen men and women sitting in the granite arcade between buildings, their knees covered with blankets, in what looked like the most linear sleepover in the world. I thought they were homeless. In fact, they were pensioners waiting overnight to receive their money from the National Building Society. Over three days, I watched the line swell from 15 to 54 to thousands. Many of the men and women hadn’t eaten in two days by the time they collected their paltry $15 (if that).

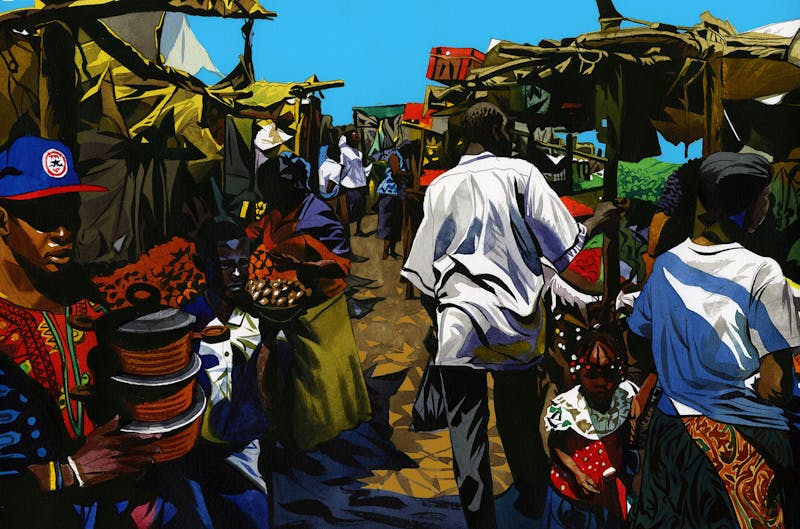

As for the truly indigent, the reason I didn’t see them in Harare proper was because they were sequestered in high-density “townships” at the edges of the city—vast shanties where the economy was entirely informal. From shacks made of wood and tarpaulin, people sold kitchenware, fertilizer, clothes, tires, vegetables, CDs—anything you could imagine. And because the townships didn’t vote for Mugabe, he had been particularly unkind to their residents. In 2005, he ordered the start of Operation Murambatsvina or “Move the Rubbish.” The slums were to be razed and cleared. Over half a million people were pushed out of livelihoods they barely inhabited in the first place. No alternatives were provided. Now, 13 years later, they were back in the townships. But they lived in fear. Even on my brief visit, I had seen pickup trucks full of cops and military police chasing away street vendors from downtown Harare.

People longed for economic change, and in his early days Mnangagwa said all the right things about the economy. One of his first moves was to reverse the Indigenization and Empowerment Act, which limited foreign investment in industries to 49 percent (investments in diamonds and platinum would still be limited). His Cabinet also tried to charm the rest of the world in order to have the sanctions lifted. At the end of a press conference, General Moyo—who was now foreign minister and dressed in a civilian suit—held on to the hand of the representative from the U.K., saying, “The diplomatic relationships that we once had, we should reestablish.” (Her response was cool: “Let’s discuss.”)

But one woman I met, who worked for an NGO and had spent a year in the Ministry of Finance, worried that the country’s liberalization could stop with economic reforms: “If people see quick wins on the economy, they will be confused, and they might decide, ‘Let’s just vote for him, we’re seeing results.’ There’ll be less emphasis on political rights.” It was plausible, then, that this was not the country’s democratic moment but its Deng Xiaoping moment—a strongman opening up the economy but not people’s lives.

Thirty-seven years of misrule by the ZANU-PF had made many citizens mistrustful. Peter, a 27-year-old who sold household goods out of a truck covered in photographs of various European soccer clubs, told me, “We’ll give Mnangagwa till May or June to see his focus, and if he doesn’t do anything we’ll kick him out.” But the question was: Would Mnangagwa or anyone in the ZANU-PF go willingly?

Mnangagwa came to power in 1980, as minister of state security under Mugabe. One of the first things he did was to visit the room with iron hooks where he had been tortured as a guerrilla; now the torturers worked for him. Since then, he had remained in power through a great deal of turmoil. As the former head of the CIO, he had overseen the Matabeleland massacres. Many considered him the chief election-rigger at the ZANU-PF.

A week into my visit, I went to have a look at Mnangagwa at the ZANU-PF’s Extraordinary Congress, the party’s convention for the July 2018 elections. The EOC was happening in Robert Mugabe Square, but otherwise all signs of Mnangagwa’s predecessor had been scrubbed clean. Instead, people wore jackets with Mnangagwa’s face on them, or Lacoste shirts and caps—the beginning of his cult of personality. A froggish man with small eyes, a big nose, and a gap in his front teeth, he arrived in a motorcade of 16 vehicles led by three motorcycles with flashing lights. Astonishingly, for a party used to Mugabe’s kingly delays, he was almost on time. Wearing a green cap, a black tie, and a jungle-decorated jacket with his own face emblazoned on the sleeves, back, and flaps, he walked to a small fenced-in area within the crowd and cut a green ribbon and planted a ceremonial tree. Then he was escorted inside for a day of speeches.

The EOC is always a huge spectacle, with about 5,000 party volunteers sitting under an extra-long white tent, but this was the most extraordinary one yet, because it was the first without Mugabe. Party apparatchiks took the stage pledging loyalty to Mnangagwa and denouncing the “G40 cabal” and even, more controversially, Mugabe. But the old leader still hovered above their heads and in their minds. Once or twice, while leading a cheer, a speaker said, “Forward with Mug ...,” only to stop himself as the audience hooted and laughed. Of course, these crowds had pledged undying allegiance to Mugabe, too, only weeks before. A dictatorship compromises everyone.

Finally, Mnangagwa rose to speak. After musically leading the crowds in chants, he said, “The first lady, Comrade … uh.” He broke into a boyish grin. This sly reference to Grace elicited even bigger laughter. The comic pause, right at the start of his speech, was the best part of his performance. Mnangagwa, unlike Mugabe, is not a hypnotic speaker. Mugabe’s power rested on his elaborately drawn-out words, his odd pauses, his British locution, his Savile Row suits with their matching ties and pocket squares. He was thin, and his voice always carried an edge of mockery. He sounded like someone sucking each word to savor it for the first time (“immoral” becomes “eeemoral”), though this did not undo the general effect of his authority: Authority has its own music, disconnected from thought or language. I remember watching a recording of his 1980 acceptance speech—where he pledged reconciliation and asked the citizens to beat “swords into plowshares”—and being moved to tears. This September, two months before the coup, he had given a similarly masterful performance at the U.N. General Assembly. He was 93 and could barely walk but had arranged his path to the podium in such a manner that he would never have to lean on another human being. Instead he put one hand on the wall to rest and continued his amble to the stage. And when he spoke, the Naipaulian-Nehruvian radio announcer’s voice was still there.

“It is axiomatic that we must harvest what we sow,” he said. “Yet by some strange logic we expect to reap peace—reap peace when we invest and expend so much treasure and technology in war.” He hit his usual high notes about colonialism. And then he mentioned a certain country that was withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement. “And that’s”—he let out an almost inaudible schoolteacherly sigh—“the United States. The great United States. Mr. Trump’s United States.” Peals of laughter came back from the crowd. “Are we having the return of a Goliath to our midst who threatens the extinction of other countries?” he asked. “And may I say to the United States president, Mr. Trump, please blow your trumpet—blow your trumpet in a musical way toward the values of unity, peace, cooperation, togetherness, dialogue, which we have always stood for.”

The General Assembly erupted in laughter and applause. A young Zimbabwean woman sitting next to me who had criticized Mugabe just moments earlier (“He’s the one who’s asleep. That’s how you know it’s Mugabe,” she had told me when I asked which of the Zimbabwean delegates was him), was clapping too. I was clapping.

Mnangagwa possessed no such powers. His voice sounded like wind in a steel tumbler: metallic, hollow, rising and falling without logic, almost unintelligible. To me his speech seemed like a round-robin of banalities, but the Zimbabwe journalists sitting on the floor with me before the dais interpreted it in the light of what had come before. They latched on to what was new—what would have been unthinkable under Mugabe.

“We must always be mindful that no party,” Mnangagwa said, “however rich its past, has a divine right to govern.” He stressed that his “ascendency to the helm of the party” did not “mean the defeat of one faction and installation of another” or “the rise in fortunes of any particular region, tribe, or totem.” He was, he said, “a president for all, men and women, the young and old, rich and poor, and the well and the sick.”

The positivity—the lack of viciousness—of the speech made it exceptional. Notable, too, was the lack of extensive flattery from the other speakers. Mugabe, I was told, had loved to hear people talking about him. And not only had the EOC unfolded more or less on time, but it had been slashed to one day instead of the expensive week of speechifying, dancing, and revelry. This was, as it were, a military operation. General Chiwenga sat just to the left of the stage. I was only a few feet in front of him, almost at his feet, and I watched the general, in his black suit, jiggle his legs restlessly. He didn’t have a role today.

The function was supposed to climax in the announcement of the two vice presidents, the next in line for the throne (would they include General Chiwenga?), but here Mnangagwa threw a curveball. “I’m delaying the appointment of these two for perhaps another few days,” he said. A pall of dismay fell over the crowd; the journalists practically put their pens away. “Disappointed?” Mnangagwa said, smiling slightly. Then the speculation began. Was it because the military now controlled Mnangagwa? Or were characters like Chiwenga still deciding whether to shed their military uniforms and enter the world of politics?

I discussed this with Columbus on the way home. “I’ve said to colleagues it’s too early to celebrate,” Columbus told me. “It’s too early to say the new era is going to change for us, in terms of press freedom, human rights, the economy, and political stability.”

He also said he was tired after weeks of reporting nonstop on the coup (he had started almost as soon as he got out of the hospital). Tired myself, I proposed we take the next day off. I agreed to pay him for his services so far.

It was a mistake. That night, after receiving the money, he sent me a message saying he was going to his village to visit his parents over the weekend, canceling our trip to Bulawayo. He implied he was upset about an agreed-upon $10 daily reduction to his fee (since he would no longer cover gas). Sensing this was a negotiation tactic, I offered more money. He never responded. But then he reappeared online again the next day and agreed to drive me to Mnangagwa’s home town on Monday. When I spoke to him on the phone the night before our trip, though, he was slurring and sounded drunk. “I am tempted to snub you,” he wrote later on WhatsApp, for no apparent reason. He didn’t show up in the morning or respond to texts, leaving me stranded at the hotel for hours. I was enraged. Maybe he deserves to be beaten up, I thought, shocking myself. After ten days in Zimbabwe, I had internalized the idea of beatings as a form of justice.

Columbus was extremely self-respecting about money, the way only people in an economically ravaged place can be; he hated discussing it, and I wondered if my negotiations had put him off. But a journalist had a simpler explanation. “See, he would never do this to a white person.” Something about this rang true: Power dynamics between nonwhites in postcolonial societies can be frustratingly opaque.

Anyway, I had work to do. The army had suddenly called a press conference at its headquarters (in daylight, thank God). I learned about it only because a journalist fretted on Twitter that he’d been waiting two hours for the meeting to begin. I rushed over in a taxi. I went first to the compound outside of which Columbus had been tortured. The soldiers at the low gate, particularly friendly when they saw my press ID, directed me to the next gate. The press conference was happening in a shabby room with ratty, drawn curtains and a scuffed fake-wood floor; army officers of different ranks and in a variety of caps sat around a horseshoe-shaped table draped in a white cloth. I made it just in time to hear a general announce, “Operation Restore Legacy comes to an end....”

“Furthermore,” the man—General Philip Sibanda, natty in a green beret and fatigues—went on:

your Defense and Security Services would like to remind all Zimbabweans to remain vigilant and to report any suspicious objects and individuals to law enforcement agents. This is because some of the members of the G40 cabal that had surrounded the former Head of State are now bad-mouthing the country from foreign lands, where their intentions to harm the peace and tranquility that exist in our country have been pronounced. It is, therefore, the duty of every Zimbabwean to ensure that these malcontents and saboteurs and others of like mind are not allowed to succeed. Today, as the Defense Forces hand over all normal day-to-day policing duties to the Zimbabwe Republic Police, we urge all our citizens to allow for a smooth transition.

And just like that, the coup was over.

Walking out, I learned from another journalist why the press conference had been delayed. They had been waiting for Chiwenga—a man I had noticed was missing. In the end, he hadn’t shown up at all. The next day, Chiwenga retired from the army and was made vice president of Zimbabwe.

Outside the press conference, I cornered the spokesperson for the army, Colonel Overson Mugwisi, and asked him about the incident with Columbus and the other journalists. “I’m actually hearing this from you for the first time,” he told me. The coup would continue to be celebrated as “bloodless.”

My time in Zimbabwe was drawing to a close. On my last three days, I saw policemen and women in fluorescent vests reappear on the streets to direct traffic. I felt a certain sadness looming in me after the inevitable return to oppressive normalcy, and I called Ed to take him up on an offer he had made earlier: to go flying in his plane.

After a long drive through maize fields, I met him at an airfield outside Harare. The land was on a seized farm, part of which was leased back to whites for flying. Outside a shed, we got into a yellow, toylike, two-seater Italian plane made of aluminum, with red slashes on the side, and a propeller built from strong carbon composite. Strapped in crosswise, our ears covered with headsets, we rolled down the grass runway and lifted off. The plane tilted sideways over the fields, and we rose to 5,000 feet, enveloped in petrol fumes. Air whirled in through two gills in the plastic windows. “This country has the perfect climate for flying,” Ed said. He often volunteered to help rangers with animal counts from the sky.

Ed drew my attention to a stretch of fallow farms below. “They make the preparations because they’re hoping they might get seed, but they don’t. It should all be cropped by now.”

The earth below us was red and furrowed, dotted with msasa trees and bald ridges and folds where illegal mining had happened. Many of the fields were crowded with kraals, which is how you know that farmland had been taken over. The farmhouses had been stripped. Their roofs had fallen through. The metal reservoirs and blue swimming pools lay empty. The man-made lakes were spotted with green weeds from human washing and waste. A white pro-Mugabe arms-dealer’s estate sat on a hill. He had his own private runway. Soon we were hovering over Grace Mugabe’s vast 3,100-acre farm, known as the “Gracelands.”

I asked if Ed had been back to his own property.

“I took the boys back to the farm two years ago,” he said, “and the people there were suspicious. I saw things I had made, like wheels, still strewn about. I didn’t feel sad. It was 17 years ago now.”

We crossed over a lush tobacco field that looked like giant tennis balls with whirling paths for irrigation. “That’s how you do it,” Ed said. A few minutes later, he demonstrated an emergency landing procedure. He cut the engine and the plane began slowly falling. If the speed dropped below 20 knots, you would go straight down; he pushed the joystick up. When the plane had almost sailed to the ground over a grassy field, he suddenly powered the engine to life. I was getting a little sick.

We passed over a Chinese-funded military base that looked like a farm ringed with pine trees. This is where the generals had been trained, and where they had learned about coups and figured out how to implement such a good one—a “model coup,” as a friend called it, or a “coochy-coup” as a journalist had described it to me.

The land below was ravaged, but it was also healthful. Anyone could see this. It was a question of what people decided to do with it.